Paul Morphy

Bio

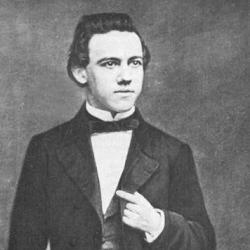

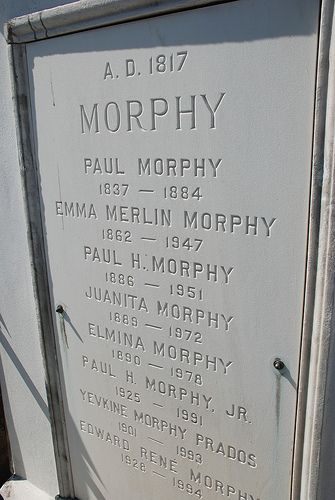

Paul Morphy was the first great American chess player and considered by many to be an unofficial world champion. He was born in 1837, stopped playing serious chess by 1860, and died in 1884. But in his brief time in the chess world, he made a lasting impression, and to this day his name is synonymous with rapid development and dominant victories.

Youth

Paul Morphy was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in the United States on June 22, 1837. A prodigy, he learned to play chess simply from watching.

Morphy’s first encounter with a master player, and indeed his only one before adulthood, came against the Hungarian Johann Lowenthal, who was visiting New Orleans in 1850. Morphy won at least twice in three games. (Sources differ on the result of the third game, whether he lost, drew, or if it was even played.)

Chess Career

Morphy’s first big breakthrough came in the 1857 American Chess Congress, a 16-player knockout tournament. He won nine out of ten games against a draw in the first three rounds to breeze into the final, where he faced the German-born Louis Paulsen. Paulsen had also not lost a game in the first three rounds, but he was no match for Morphy. Even though Paulsen did win a game, Morphy won five and drew two. His most notable win came via a queen sacrifice with Black, out of the Four Knights opening.

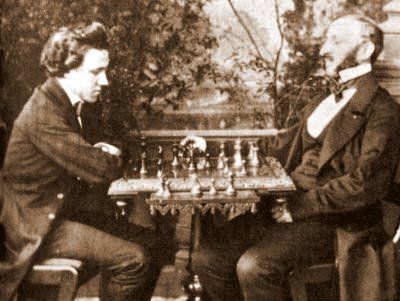

Morphy was just 20 years old at the time but was already considered one of the world’s top players. However, Morphy had not played many of the best European masters, and so the next year, in 1858, he traveled to Europe. There he played several matches. Perhaps none were more important than his bouts with German star Adolf Anderssen, as they were likely the two strongest players in the world at the time.

Morphy beat Anderssen in a rout, winning seven of the eleven games against two defeats and two draws. Anderssen, of Immortal Game and Evergreen Game fame, reduced himself to playing 1.a3 as White in multiple of the contests. Morphy lost one of those games, but was so dominant otherwise it did not matter. Morphy won three of the games in 25 moves or less, including the following 17-move victory.

Morphy was ostensibly in Europe not to play Anderssen, but rather to face the English master Howard Staunton, coincidentally the inventor of modern chess piece design. Writing after Morphy’s death in 1884, Charles de Maurian of the newspaper of Morphy’s hometown of New Orleans stated that Staunton “first accepted, then postponed, then clearly sought to evade and finally peremptorily declined” the match.

Whatever the reasons--and Staunton’s health may have been more of an issue than any recalcitrance--the match never occurred. Staunton peaked as a player the decade before and likely would have stood as little chance as anyone else against Morphy. Nonetheless, it is still a loss to chess history that they never played.

While in Europe, Morphy did not just play Anderssen and miss Staunton, however. He played matches against masters Henry Bird, his 1850 nemesis Lowenthal, Daniel Harrwitz, and Augustus Mongredien, among several others. None of these opponents were considered to be of Anderssen’s quality, but Morphy nonetheless won roughly two-thirds of his approximately 50 serious games against them, with the non-victories split between draws and losses. A player might beat Morphy once or twice, but Morphy’s advanced play was nearly impossible to overcome long-term.

The Opera Game

Much of Morphy’s brilliance showed against weaker players--one might say amateurs, but for all his success Morphy never pursued chess professionally himself. Few players of his time did.

And for all the matches Morphy played against top players, no game of his is more famous than the one against two continental European aristocrats during an opera in Paris in 1858. Many players dream of winning a sacrificial miniature, but Morphy could do it with ease. Rumor has it he merely wanted to enjoy the show and thus sought the quickest path to victory. That meant his signature rapid development of pieces, followed by sacrifices of a piece, an exchange, and finally his queen to deliver mate on the 17th move.

The score of this game can be found at the end of the bio.

After Chess

Morphy’s chess career, if defined by regular competitive play against master-level opponents, effectively lasted less than two years: from the American Chess Congress in October 1857 to his return from Europe in May 1859. What happened?

Essentially, he got bored. He claimed he would begin only playing matches where he would give his opponent “pawn and move” odds -- where Morphy would take the black pieces without his f-pawn. No one accepted, and so Morphy turned to law, his professionally available career path. The U.S. Civil War erupted soon after; being from Louisiana, Morphy was on the wrong side of history in that one, but there is no undisputed record of him serving in the military.

Whether it was the war, the reported exuberance of his would-be clients only to discuss chess, or weaknesses in Morphy’s personality (or perhaps all three), his career in law came to nothing and he began to live a life of idleness from which he never escaped. Morphy would pass at the age of just 47, on July 10, 1884.

Legacy

Richard Reti, in his Modern Ideas in Chess from 1929, stated that Morphy “had a wonderful talent for combinations” and declared him “the first positional player.” Reti attributed to Morphy the realization that development is of utmost importance in open positions. Morphy generally continues to receive such credit to this day.

Bobby Fischer said in 1964 that Morphy “was perhaps the most accurate player that ever lived” and that he could find “winning possibilities in situations that looked hopeless.” Morphy’s contemporaries like Anderssen and Lowenthal who said similar things about Morphy’s ability to reverse hopeless-looking positions.

Morphy was clearly the best player of the late 1850’s, and as such can be considered an unofficial world champion. His revolutionary understanding of open positions changed chess for the better. As much as we might want Morphy to have played chess for longer, it is just as remarkable that he achieved so much in so little time.