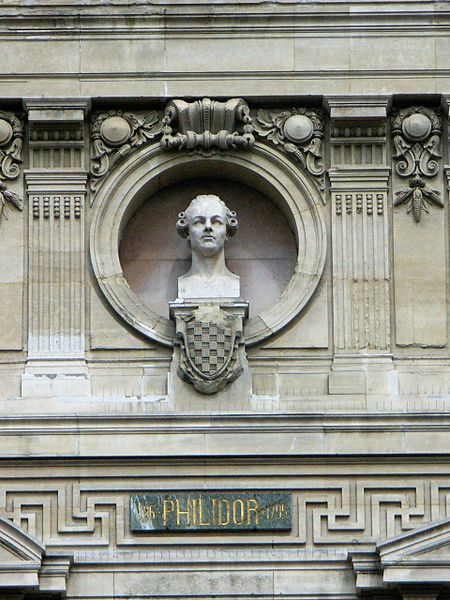

Francois-Andre Danican Philidor

Bio

Francois-Andre Philidor was a French chess player and author. He was arguably the first modern player with a real positional, not just tactical, sense. Best known for his focus on pawn play, he also has an opening, an ending position, and a checkmate pattern named after him.

Early Life

Philidor was born in 1726 in Dreux, France, a town of about 5,000 (by the late 18th century) that is now about an hour’s drive west of Paris.

Philidor was raised in a musical family, but his chess interest developed early on, in Paris around the year 1740, when he would have been a young teenager. (Philidor never left music, however, composing 30 operas between 1756 and 1796.)

Philidor’s teacher, Legall de Kermeur, is best known today as the namesake of an opening checkmate. But Legall also became part of that long line of teachers, in chess and many other fields, who would be surpassed by their most talented students. Philidor quickly had no need for his original rook odds.

Playing Career

The French chess scene in the time of Philidor was concentrated in one place: le Cafe de la Regence—the Regency Coffeehouse in Paris. It was there where he gained his reputation as the best chess player in the country. He also spent nearly a decade abroad in Holland and England, growing his reputation across the continent.

Most games were casual and none were recorded, especially in the 1740s. In fact, the only record we have of Philidor’s games before 1780 is from his book, and he did not identify who played the games found in it. Several were likely compositions, and Philidor often included variations of how a game may have diverged at certain points.

However, due to the popular acclaim surrounding Philidor—arising out of match victories against Philip Stamma and Abraham Janssen as well as his dominance in blindfold exhibitions—there is no player who has a claim to being as strong as he was by the mid-18th century. He remained a strong player well into his later life, with perhaps his best-known game coming against a Captain Smith in 1790 (available at the end of this page).

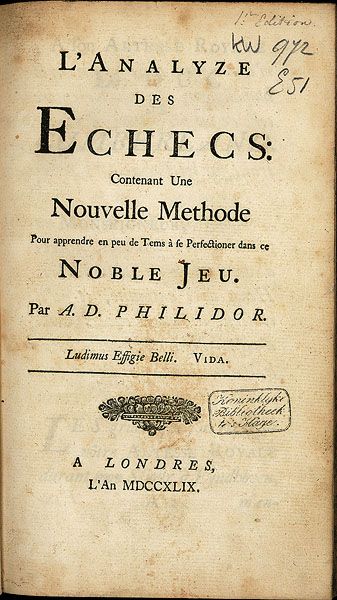

L'Analyse du jeu des Echecs

Within just about a decade of learning chess and already dominant on the scene, Philidor wrote one of the game’s first great strategical tracts: L’Analyse du jeu des Echecs—Chess Analysis. (Its first edition title—L'Analyse des Echecs: Contenant Une Nouvelle Methode Pour apprendre en peu de Tems a fe Percetioner dans ce Noble Jeu—rolls off a native French speaker’s tongue!) First published in 1749, it was reprinted in 1777 and 1790.

It was not the first chess book. In the centuries before Philidor, Luis Ramirez de Lucena, Ruy Lopez de Segura, Pedro Damiano, and Gioachino Greco had all disseminated their chess knowledge to the western world. As important as they were, however, their books and manuscripts focused mostly on basic openings and tactical problems.

Philidor was the first to espouse grand strategic principles, which he had used to become the dominant player, and have them widely read. Where Greco would have an eight-move game ending in checkmate, Philidor might have three versions of a 40-move game, each with its own educational purpose.

Philidor On Pawns

Nothing became more emblematic of Philidor’s breakthroughs than the use of pawns. Rather than their most popular use at the time—being sacrificed at a moment’s notice for the glimmer of an attack—Philidor was much keener on pawns’ other uses. They could control the central squares as well as open or close files or diagonals; passed pawns were valuable as future queens, while backward and isolated pawns were weaknesses to be avoided. Pawn chains were strong formations.

Philidor in a way even anticipated the hypermodernism of the 1920s, more than a century and a half later, warning that pawns must be “sustained by one another, and also by your pieces” [emphasis added].

Even though he was an obviously successful player—best in the world by acclamation—Philidor’s new approach was controversial. His critics actually won out in the end on some issues, namely Philidor’s preference of 2...d6 to 2...Nc6 after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3.

On the whole, however, criticism of his ideas ended up similar to the reaction Wilhelm Steinitz received a century later when reinventing what chess could be. Eventually the new methods prove so superior to the old that they must be adopted, or at least taken quite seriously, if a player is to survive.

Legacy

Although no recorded games from Philidor’s prime years (by 1780 he was 53 years old) and very few games overall survived, he left an indelible mark on chess thanks to his book and the strategies outlined in it.

And Philidor was about more than just pawns, too. He has several chess concepts that bear his name. There’s the opening, now regarded as passive but still popular at certain levels. Several endgames are named after Philidor, most notably the drawn position in a rook-and-pawn ending. There’s Philidor’s mate as well, although he did not discover it, and you probably know it by another name: the smothered mate.

We know more about chess today than ever before, and Philidor took us on many of the first steps on that path.