FIDE Likely To Make It Harder To Become A Grandmaster, But Will It Be Enough?

The FIDE Management Board is currently looking at proposals for tightening grandmaster norm criteria. It is part of a larger debate that followed upon Abhimanyu Mishra becoming the youngest GM in history by playing a series of round-robin tournaments in Budapest, Hungary.

Mishra became a grandmaster on June 30 of this year, when he was 12 years, four months, and 25 days old. In doing so, he broke GM Sergey Karjakin's 18-year-old record.

The grandmaster title is the highest title in chess (apart from world champion) and is granted for life by the International Chess Federation (FIDE). Although the term was used before, it reached an official status in 1950, when FIDE awarded it to 27 players. In 1970, grandmaster norms were tied to "norms" and the Elo rating system, which was introduced shortly before.

These days, players are eligible for the title when they reach an Elo rating of 2500 and play at grandmaster level over a series of 27 games. In practice, this usually comes down to achieving GM-norms, i.e. a performance rating of over 2600, in three nine-round FIDE tournaments. In those three tournaments, several of the opponents must be from federations/countries other than their own and also be titled.

In 1979, FIDE had changed the norm from a 2550 performance to 2600. When rating inflation seemed to become quite apparent, raising the norm to 2625 or 2650 was considered in the 1980s but the then FIDE President Florencio Campomanes wanted "a GM in every country" so the norm didn't change.

Twitter debate

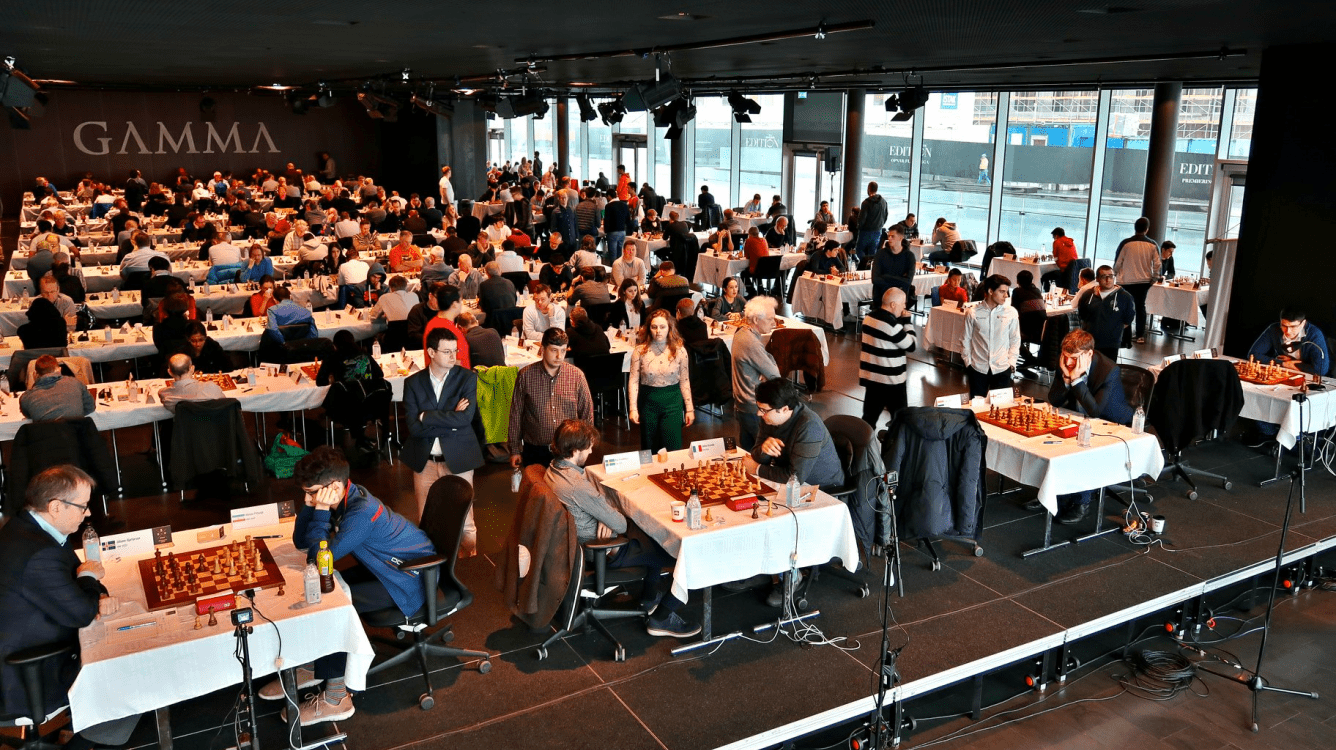

The way Mishra earned his GM title led to a discussion of which some prominent figures were part. Spending several months in Budapest, the teenager from New Jersey played six tournaments in a row in the same playing hall, often against the same players and often against grandmasters rated under 2500.

None other than world championship challenger GM Ian Nepomniachtchi lit the fire of the debate with a tweet on the same day Mishra made the title. He referred to the level of Mishra's grandmaster opponents and the fact that all norms were scored in closed tournaments.

I’m dazzled with the new record, so I’d like to suggest some changes to the order of conferring titles. For example, one of the norms must be fulfilled in an open tournament, and the participation of 2400 GM luminaries in stamping new titles should be finally limited. @FIDE_chess

— Yan Nepomniachtchi (@lachesisq) June 30, 2021

Mishra's Twitter account, which is most likely handled by his father Hemant Mishra, replied with the following tweet:

@lachesisq Thanks. I am very positive guy and would take that as compliment to dazzle world champion challenger. On a lighter note it would have made more sense to suggest these awesome suggestions when you were approaching your GM title.

— Abhimanyu Mishra (Youngest ever Grand Master) (@ChessMishra) July 2, 2021

Chess professional Lennart Ootes thereupon did some research where he compared the results of both Nepomniachtchi and Mishra for the events where they became a grandmaster. Mishra followed a legal path to earning the grandmaster title during a time of pandemic with few options for tournaments to choose from, but his list of opponents in Budapest seemed weaker than usual. The data showed that the average rating of Mishra's opponents was 2390 (while 2513 for Nepomniachtchi) and that of the 10 grandmasters he played, five were rated 2437 or lower.

Here is a list of the opponents of @lachesisq and @ChessMishra for their respective GM norms. Nepomniachtchi made his norms in Wijk aan Zee C (2006), European Championships (2006) and World Youth Stars (2007). Mishra made his norms in GM-norm tournaments in Budapest. https://t.co/hMmkYdFWnq pic.twitter.com/A6ojcRqcbd

— Lennart Ootes (@LennartOotes) July 3, 2021

On the other end of the spectrum was GM Magnus Carlsen, who reacted as follows to Mishra's achievement:

"It's a pretty nice achievement and I would say especially considering that he went to Hungary to play basically non-stop for a couple of months to get his norms. I could see on the one hand that gives you a better chance to get the norms but it also means that these tournaments are practically organized for you to achieve this particular aim so it also puts a lot of pressure on you. I'm really impressed that he achieved this feat."

I'm really impressed that he achieved this feat.

—Magnus Carlsen

New York Times

Two weeks later, the New York Times jumped on the story with a piece dramatically titled The Dark Side of Chess: Payoffs, Points and 12-Year-Old Grandmasters. Before mentioning the Mishra story, this article mainly focused on how the earlier record by Karjakin was established.

Karjakin became a grandmaster in August 2002 at the Great Silk Road tournament in Sudak, Crimea. According to the testimonies of some participants, this event saw a number of irregularities. The New York Times article is largely based on an open letter from 2006 by Vasily Malinin, the tournament winner in 2002, who passed away in November 2020.

Malinin, who was a Doctor of Law and member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, stated in his letter that his regular tournament game with Karjakin had ended in a draw but was then replayed after the tournament was over. Karjakin had missed out on his third GM norm by half a point due to an unexpected draw in the final round with Irina Semyonova. In the replay, which was reportedly a blitz game, Karjakin beat Malinin. The full point was counted in the final standings and Karjakin became the youngest ever grandmaster aged 12 years and seven months.

The Ukrainian IM Anatoliy Polivanov, another participant, gave a somewhat different account in a book about the infamous Sudak tournament which he published in 2016. He wrote about the initial game between Malinin and Karjakin:

"The game was not played as scheduled and was postponed. It was rumored that Malinin was not ready to play because of a swimming accident (ears filled with water). However, I think that both participants decided to take a pause and see the standings at the finish of the tournament. If the draw would be OK for both, why bother. Near the finish, when it seemed that both would get their norms, a draw appeared in the crosstable, but that was not the end of the story..."

According to Malinin, Karjakin's father had approached several players to whom his son had lost points and offered them money to replay their games. Karjakin denied this to the New York Times, saying that it was Malinin who had tried to extort money from his family for simply playing a game that they had agreed to postpone, not replay.

The newspaper also spoke to GM Alexander Areshchenko, who played in the Sudak tournament as well and was slightly higher rated than Karjakin at the time. "He could not do it honestly," Areshchenko was quoted. "I played better than him at the time, and it was tough for me to become a grandmaster then.

Speaking to Chess.com, Areshchenko said he was not impressed by the New York Times's reporting: "In our interview, the journalists asked me if Karjakin was happy. I answered: 'Naturally.' Then they asked me if he was happy as a peacock. I answered: "Very happy." And then the article ascribes to me the words 'after that game Karjakin left the hall happy and proud as a peacock.'"

According to Areshchenko, the New York Times wrongly sends the message that the Sudak tournament was organized to provide a norm to Karjakin. "This is wrong," said Areshchenko. "The main beneficiary of the tournament was Malinin. That was a guy whose real level was about 2300 and who decided to become a GM. Malinin had a higher rating at the time of that tournament, but I saw his games and understood he did not get that rating in a fair way."

FIDE Proposals

In a response to the debate, the FIDE Qualification Commission invited federation representatives, FIDE officials, and other interested parties to attend two open meetings discussing proposals to change FIDE's rating and title regulations. The meetings were held on July 19 and 21, 2021.

Alex Holowczak, the secretary of the commission, kindly sent a summary of the three main proposals that came out of these meetings. The proposals have been sent to the FIDE management board and from there they will go to the FIDE Council for final approval. An exact timeline isn't clear at the moment; the next meeting of the management board hasn't been scheduled yet.

The three proposals are:

1) Any title application containing a norm not achieved before June 30, 2022, must include at least one norm from an individual Swiss tournament with every round containing at least 40 participants whose average rating is at least 2000. For this purpose, players will be counted only if they miss at most one round (excluding pairing allocated byes).

This proposal is similar to what Nepomniachtchi suggested. According to Holowczak, it is an attempt to respect the round-robin format—which is still an extremely common format for chess tournaments and the vast majority of which arouse no suspicion at all—while also including a more sizeable tournament as part of the overall title application.

2) Reports must include a PGN file. For Swiss and team tournaments, this should at least contain those games played by players who achieved title results. For other tournaments, all games will be required.

This proposal will make life easier for the Qualification Commission and the Fair Play Commission to investigate events that are under suspicion of irregularities. It should be noted that although the submission of the PGN will be mandatory, there will be a pragmatic relaxation for Swisses and team tournaments which tend to be rather large.

3) In tournaments with pre-determined pairings, a norm must be based on all scheduled rounds.

Holowczak explains: "In, let's say, an 11-round Swiss, if you get your norm after nine rounds, the norm is "banked", for want of a better expression, to avoid people withdrawing from the tournament, or in the case of a team tournament refusing to make themselves available for selection, to protect their norm. Previously, in a round-robin with e.g. 12 players, a player was able to bank their norm after round nine if they achieved it, in the same way as they could in other types of tournament. There were allegations in some tournaments that the drawing of lots would be manipulated so that a norm seeker might get precisely the opponents they needed in rounds 1-9, and then the round 10 and 11 games didn't matter. It was thought that in a round-robin, there is an expectation—sometimes even a contractual obligation—that the player would play in all of the games. The aim of this proposal is to remove any allegations of abuse in the drawing of lots."

Will it be enough?

Short term, it seems impossible to fully eradicate what we continue to call "irregularities" at tournaments. For instance, it is virtually impossible to prevent players from agreeing to a draw (or even a decisive result, for that matter), and having access to such a game in a PGN will be easy to handle as players can simply make up their moves and agree on playing those beforehand.

This author hereby admits having done so once in an official tournament. One game I played with a good friend at Hoogeveen 2006 was fabricated from start to finish since we simply didn't feel like playing each other. We decided to add a funny twist by repeating Mamedyarov-Topalov, which had been played in the same venue just days before, and improve on move 35. We were hoping to one day find a book that would write: "Here Topalov errs. Better is 35...Rxc8, as in Doggers-Woudt..."

Whereas this example is rather innocent, as it was played at a lower board with no other players really being affected, it is well known that pre-arranged games continue to happen and have an impact on the final standings and distributed prize money at tournaments. Carlsen's second GM Peter Heine Nielsen admitted in once doing so:

20 years ago, on this day, I was offered and accepted a pre-game draw proposal by @EmilSutovsky as it would mean we shared first in the North Sea Cup.

— Peter Heine Nielsen (@PHChess) July 14, 2021

FIDE is turning is blind eye to pre-arranged draws, which indeed is hard to fight efficiently but shouldn't be part of our game https://t.co/SsoMVUFUJK

Areshchenko told Chess.com that at the Sudak tournament in 2002, he was involved with pre-arranged draws in two games. One of those was with Malinin.

"I was told to make a draw, but I was ambitious and did not like it. So, at first, I refused but then was persuaded and even got some money. I told the New York Times that I do not remember exactly, but it seems to me that there was something. That was my sin."

Areshchenko also agreed to a draw with Karjakin before the game. He explains: "We both studied at the same chess school in Kramatorsk, so to refuse was not an option. It was a command from the above. I played Black in that game and Karjakin was a strong opponent, so a draw was OK. I was a bit stronger, I defeated Karjakin in our previous games and did not really want to make a draw, but OK."

While speaking to Chess.com, Areshchenko several times referenced Polivanov's 2016 book about the tournament and confirms that it is fairly accurate, such as that the Malinin-Areshchenko game (a 10-move draw according to the database) was drawn "before other players entered the playing hall."

Polivanov's description of Malinin's game with GM Gennadi Kuzmin is similar: "Same as the game versus Karjakin, it was not played in time. We saw only the scoresheets with a 22-move miniature at the arbiter's table. Nobody knew how and when it was played."

Areshchenko also confirms Polivanov's records of the Karjakin-Malinin game, saying: "In the tournament table, the result of the game between Malinin and Karjakin was a draw, but I didn't see them play this game. This draw was the same as the draw between me and Malinin. After the game with Semyonova and Karjakin's failure to fulfill the norm, he and Malinin allegedly "finished playing" the game. In general, this was of course pure fiction. Nobody finishes a game after the final round. Also, these games are not played in 10 minutes. And I will repeat once again, by that moment the result in the crosstable was a draw and everyone knew about it. All this is perfectly described in Polivanov's book."

Although the New York Times' focus on the Sudak tournament feels unnecessarily amplified and the paper seems to suggest that Karjakin wouldn't have become a top grandmaster if he hadn't made his norm there, they rightly address the issue that it is possible to manipulate results in chess, perhaps easier than in other sports. In fact, many players don't see a problem with it.

Areshchenko: "A draw agreement before the game is something that exists in chess at all levels. Back in 2002, there was no such thing as Sofia rules. It is not even considered unethical."

Among the games that Mishra played in Budapest were a five-move draw and a 13-move draw with the same GM Gabor Nagy. These need not have been pre-arranged; that's not the issue here. Doing something against the mere possibility of fixing games is the biggest challenge FIDE has if it wants to work toward "cleaner" titles in the future.

Yury Solomatin contributed to this article.