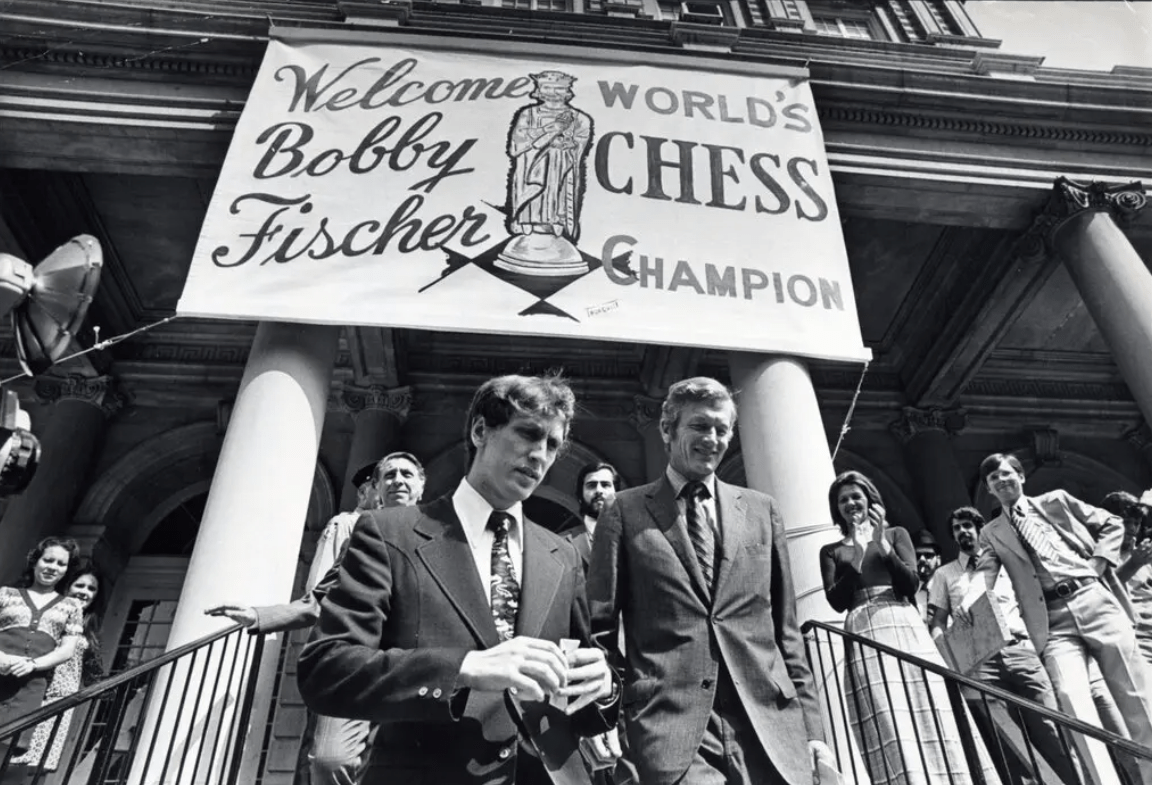

How Shelby Lyman Mesmerized Millions During 1972 Fischer-Spassky Match

Fifty years ago, during the Fischer-Spassky world championship match, one name in the United States became a household word: Shelby Lyman. In the era before streamers, social media influencers, online news sources, and even the internet itself, his name stands out for bringing chess to the attention of millions. How much of his story do you know?

- Watching Fischer-Spassky Match On Television

- Planning The Fischer-Spassky Broadcast On PBS

- Who Was Shelby Lyman, The Program Host?

- Attracting Viewers In Bars And Restaurants

- Bell Sounded Next Move

- Lyman From Broadcaster To Syndicated Chess Columnist

- Lyman Brought Chess To Millions

Watching Fischer-Spassky Match On Television

Can you imagine chess fans being connected not to TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or Twitch but to a Public Broadcasting System (PBS) station for the latest move in a celebrated chess game? How about being in a bar with rows of TV sets and eyes focused not on basketball, football/soccer, American football, or baseball but on the royal game of chess?

Turn back the clock to 1972. Although GMs Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky were the gladiators in the World Chess Championship match, it was Lyman who explained on public television what each move meant. When someone says that they remember watching the Fischer-Spassky match on television, what they really mean is they remember watching Lyman.

Planning The Fischer-Spassky Broadcast On PBS

Much credit for igniting the “Fischer Craze” goes to Lyman, who teamed with TV executive Mike Chase, director of operations for the New York Network of the State University of New York, to bring the 1972 match live to a mass audience. Chase, who had been one of Lyman’s chess students, set up an open phone line to Reykjavik, obtained several large chessboards, and positioned Lyman in an available studio in Albany, the state capital.

Channel 13, the PBS station in New York City, broadcast the show because they received it for free. Because Fischer was a hometown hero in Brooklyn, Chase thought a show would resonate with the public television audience in the metropolitan area. As it was aired on WNET (Channel 13) in New York and broadcast across the state, the show was also picked up by stations in Boston, Philadelphia, and other U.S. cities.

In a 2001 article in Wired, Chase reflects: “No one believed chess could be a spectator sport. The way to present a match was by postgame analysis. But I realized at tournaments, that a lot of the excitement came from guessing what the next move would be. The only way to capture that excitement was to televise the games live.”

How did the show get started? In a conversation with a blogger for The New York Times, Lyman said: “One day I suggested [to Chase], with the Fischer-Spassky match coming up, would it be possible to put something on PBS. Between the two of us, we got this thing going.”

Initially the match was not scheduled to be televised live. Fortunately, it was occurring during the slow summer months. The first plan was to broadcast the match for just two hours with updates. The plan changed quickly, and the program “became a five-hour, move-by-move show,” as Lyman told The New York Times in 2008.

Who Was Shelby Lyman, The Program Host?

Lyman was an unlikely choice to host the program because he had no television experience. However, his charming innocence and sometimes bumbling mannerisms won over the large television audience. In “The End of the Golden Era of Chess,” Peter Nicholas explains: “Lyman proved a natural showman, explaining densely complicated chess positions to TV viewers, many of whom thought of a fork only as an eating utensil.”

To Nicholas, Lyman confessed: “I had no concept of TV. I never watched television. I had no idea how a talk show host should act…. Chess is a dramatic event. You could hear the swords clang on the shields with every move. They went at each other. The average person is turned onto chess when it’s presented right. Trying to figure out the next move is a fascinating adventure—an adventure people can get into.”

I had no concept of TV. I never watched television.

—Shelby Lyman

Lyman, who learned to play chess when he was nine from his uncle Harry (considered the “dean of New England chess”), was at one time the 18th-highest rated player in the United States. In 1972 at age 35 before his stardom in front of television audiences, he was teaching chess full-time after having been a sociology lecturer at the City University of New York for three and a half years.

Attracting Viewers In Bars And Restaurants

Within a week, the show was attracting a million viewers in New York City alone. Another million elsewhere in the United States were also watching. Rather than featuring the players, the show featured Lyman. As he stood in front of a studio camera, he narrated, analyzed, and recreated the game move for move as it was being played in Reykjavik.

The audience continued to grow. According to Lyman, “We had the largest audience in the history of public television, doing chess. And of course, at that time, according to a Harris Poll, only 20 percent of the adult population over the age of 18 knew the moves of the game.”

When a New York newspaper surveyed 24 bars and restaurants in Manhattan, 17 had TV sets and 15 were broadcasting chess. At the time, the show was the highest-rated U.S. public television program and greatly surpassed viewer expectations. In People magazine, Lyman remarks: “In 1972, I would walk down a city block, and 50 people would come up to me. I was the hottest thing in town.”

I was the hottest thing in town.

—Shelby Lyman

Bell Sounded Next Move

When a move came in, a bell in the studio would ring, and Lyman would announce: “We have a move.” A staff member brought a piece of paper that identified the move. Then Lyman hurried to the “master board” and moved the piece to its new square. In an interview with Chicago Tribune in 2002, Lyman said that he interrupted what he was talking about or stopped what he was doing. "If I was talking to God, I stopped and made the move,” he said.

Really? A bell? Because you might not have been watching, let Lyman confirm: “It was one of those little teacher bells where you hit the top and it goes ding-a-ling-a-ling. We didn’t have anything else. It wasn’t because we knew it would be so effective. It was.”

Lyman From Broadcaster To Syndicated Chess Columnist

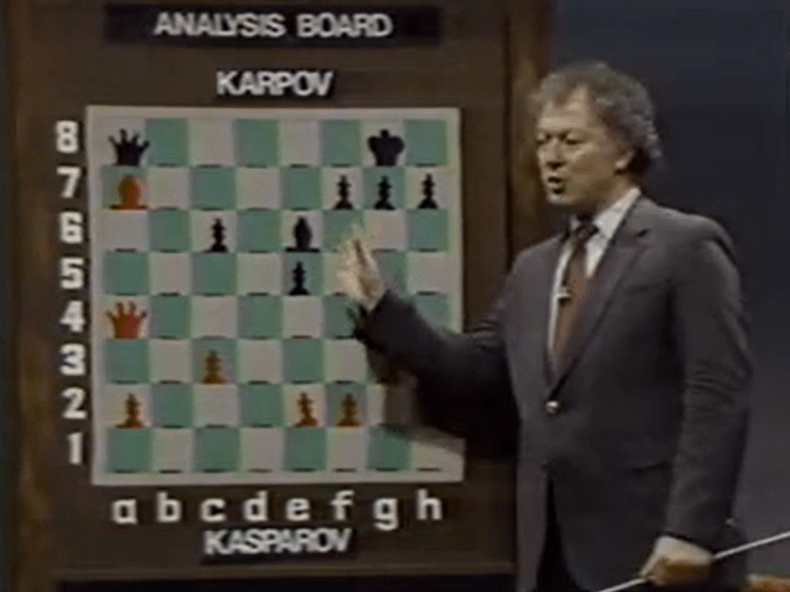

Lyman had two boards — one to show the current position and the other to analyze it. He said: “We had a demonstration board where we analyzed and then we had the game board. That was one of the best things for me — that physical movement. It actually got me into a rhythm of doing the match.”

Lyman made the players very personal, almost acquaintances to his viewers, by calling them “Boris” and “Bobby.” Regular guests on the show included GM Samuel Reshevsky, IM Edmar J. Mednis, IM James T. Sherwin, NM Bruce Pandolfini, and WIM Rachel Crotto.

Incidentally, for the show, Lyman was paid nothing (although his expenses were covered). His fame from the 1972 show did propel him into writing. For years, he had a syndicated chess column for Newsday that was published in 82 newspapers worldwide at its peak. In 1986, he also broadcast the world chess championship match between GMs Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov.

Lyman Brought Chess To Millions

Unfortunately, no video account of the 1972 broadcast was preserved. However, a video of Lyman in 1984 as he covered game 26 of the match between Karpov and Kasparov that aired on 120 public television stations is still available and provides a sense of his style.

Lyman died at age 82 in 2019. His obituary by U.S. Chess credits him with “bringing chess to millions of people who, in other circumstances, might never have been exposed to the game.” In an obituary, The New York Times called Lyman “an unlikely choice for television.”

Shortly after his death at a memorial event at the Marshall Chess Club, FM Asa Hoffman said that Lyman’s “show had a mesmerizing effect on people and inspired thousands to start playing serious chess.” To The New York Times earlier this year, Hoffman added: "The Shelby Lyman show was just as much responsible for the Fischer boom as Fischer was himself because it captured everyone’s imagination.”