Winners' POV? Wiesbaden 1880

We're doing things a little differently today.

In 1898, American chess player and journalist Gustavus Reichhelm wrote an article for American Chess Magazine (and a revised version in Chess in Philadelphia) simply titled "Fifty Tournaments," which was a summary of what were considered to be the 50 most important tournaments in history up to that time:

The reason why I'm telling you this is because this article made for a natural starting point when I was planning this series - I had a selection of 50 tournaments that were considered important picked out for me, which automated a lot of the decision making process. While not every tournament I've written about is on this list (like London 1876 and St. Petersburg 1879), I have so far included every tournament within this article, even when I didn't necessarily want to (like the BCA congresses in the late 1850s, or London 1872).

The reason why I'm telling you this is because the next tournament on the list is Wiesbaden 1880, and I must say, it has been the most surreal tournament thus far, from both a research and logistical perspective. To address the former, there is such a small amount of documentation about this tournament, comparable to the aforementioned BCA congresses from two decades prior; chessgames.com doesn't have a tournament page, German periodicals for this time are still impossible to find on Google Books, and I don't think there was a tournament book produced. I did find some key details of the event in Johannes Zukertort's Chess Monthly magazine, which makes sense given that he was present at the congress (but didn't compete), but it's still shocking how little documentation such an event has given how often I've seen it referenced in later writing.

Format and Prizes

The usual German format returns, with two games being played per day at a time control of 20 moves per hour. However, the number of players was increased to 16, including some top names from all over Europe.

The top three prizes were 1000, 500 and 250 marks respectively. 1000 marks was worth £50 at this time, so while we can't get an accurate representation of today's value, we can compare it to other tournaments. To contrast this, the entire prize fund for Leipzig 1879 was 1150 marks, so this represents a very large improvement in terms of a prize fund.

Players

Per Chess Monthly (taken from the final crosstable so it's a little small):

What a field! Edo claims the top seeds are Joseph Henry Blackburne (3rd in the world behind Wilhelm Steinitz and Zukertort), Berthold Englisch (4th), Szymon Winawer (7th), Louis Paulsen (9th), Adolf Schwarz (10th), James Mason (11th), and Henry Bird (13th). With this many members of the world's elite, you hopefully understand why I wanted to cover this tournament, even if things get even more awkward...

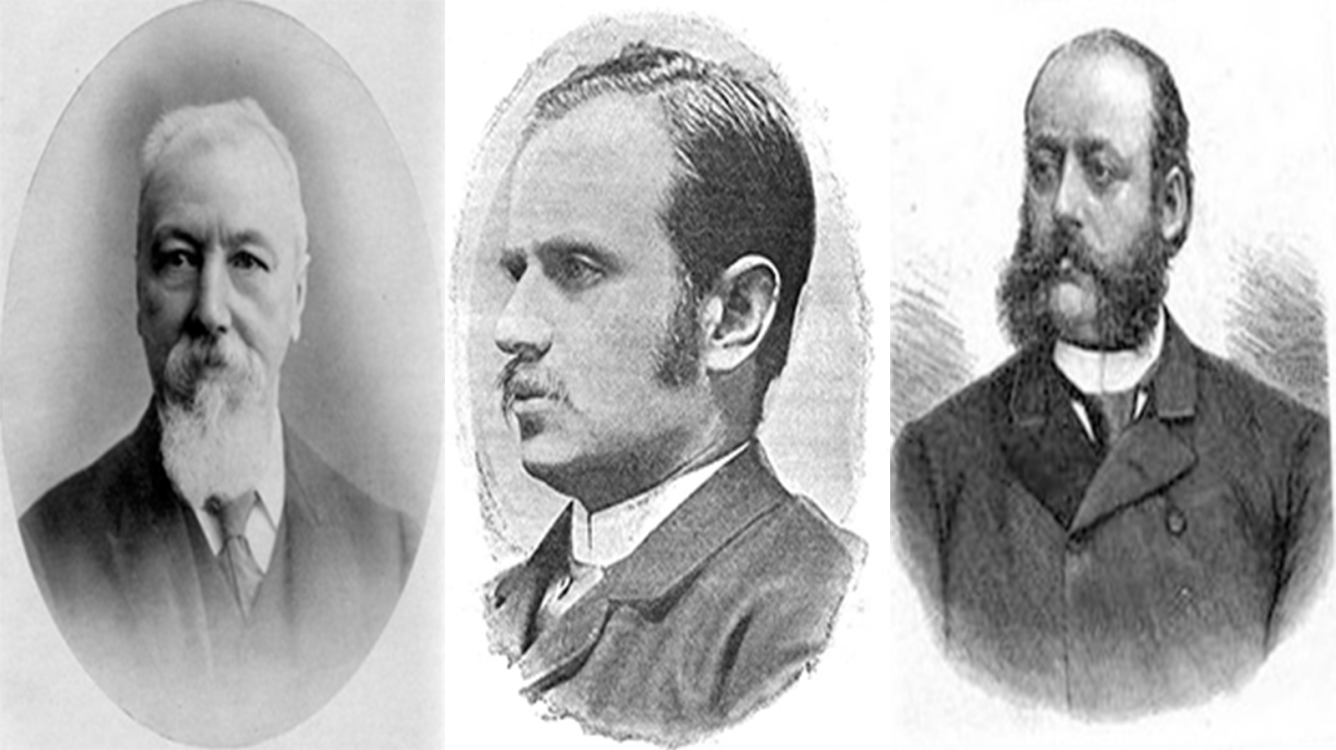

The Winners: Blackburne, Englisch, and Schwarz

Yes, for the first time in this series, we have a tie for first (but not the last, though I have a different plan for those) that was not resolved with a tiebreak. Now this isn't all bad, as none of these three players have surviving game scores for every single game; what we do have is at least one game for each round. Thus, we're going to do things a little differently this time, in that we'll be jumping around to each player and showing one game per round from one of these gentlemen. Sound good? Then let's try to look at the Wiesbaden 1880 tournament from the Winners' POVs.

Round 1: Wilfried Paulsen vs. Adolf Schwarz

We start our tournament with two second bests, with Wilfried being the "other" Paulsen brother and Schwarz trailing Englisch as the best Austrian player (aside from Steinitz, though I reckon he considered himself English at this point). Schwarz presently leads their head-to-head 2-0, but Wilfried has a golden opportunity with the White pieces.

The players began with a line of the French Defense that both Paulsen brothers had been testing Schwarz in over the last two years. The trend did not change with this game, as while the short affair was messy all around, Paulsen made the last major mistake. His 15th move allowed Schwarz to make a dangerous passed pawn on c3, and it took him only four moves to promote it. We all love a cute miniature to start off our tournaments, yes?

Round 2: Johannes Minckwitz vs. Berthold Englisch

The last time we saw Minckwitz was at the 1879 Leipzig event, where he lost against Englisch in the first round and finished with a disappointing 2.5/11 overall. Like Wilfried, Minckwitz has an ideal chance for revenge with the White pieces, though we all know how hard it is to beat Englisch, so he has his work cut out for him.

Englisch opted for the Scandinavian in this game, which makes sense with his style; it's a solid opening that offers no tension in the early game. He kept his cards close to his chest, developing only one piece past his 3rd rank before castling and forcing Minckwitz to commit to something. This proved to be correct as Minckwitz just dropped a pawn with his 12th move, and when paired with a precise tactic that traded multiple pieces, we had a classic Englisch endgame. As per usual, the defence was not nearly enough to hold on.

Round 3: Adolf Schwarz vs. Szymon Winawer

In an effort to not show the same player twice in a row, it makes sense to show Schwarz here as the next game will be Blackburne's. This game also deserves to be shown on its own merit, or at least on the merit of the rivalry present; Winawer lost a short match 1-3 elsewhere in 1880, and with Winawer being one of the best players in the world, any person who can beat him in a match (no matter how short) deserves attention.

This game was our third or fourth time looking at this Double Spanish opening where White plays 5. Nd5, and one that Englisch would face no fewer than three times in this tournament (as we'll see later). The position was symmetrical until move 9, at which point Schwarz went for a promising setup with his Bishop pair both pointing at the Kingside. Had he taken en passant on move 14, he'd have had a very fine game; when he didn't, both of his Bishops were left relatively lame, and the game had no drama in the remaining 35 moves.

Round 4: Henry Bird vs. Joseph Blackburne

We've yet to see Bird win a game in this series, and Blackburne might not be the person to face if this streak is to be broken. The momentum does seem to be on Bird's side, however, as after finally drawing his first blood at Paris (Blackburne had won their first four encounters) he had scored 2.5/3 in their next two competitions. Perhaps today is the day we feature our first Henry Bird victory.

Blackburne was very adventurous with his openings in this event, and this Modern game would've been among the more tame examples had he not played the incorrect 5... b6. Bird got a significant central space advantage, and while Blackburne's decision to expand on the Queenside made sense in principle, it didn't actually give him much of a plan as two of his minor pieces idled on the Kingside. He was allowed to castle on the Queenside once it was locked down, and thus escape any immediate King danger, but Bird's position was quite fabulous.

We've seen Bird struggle to maintain an advantage without a knockout blow before (Bird - Mason 1876 being the particular example in my mind), and it happened again here. Blackburne began to win the maneuvering battle after Bird's 23. a4, as his Knights wove their way into the position. At the critical juncture, Bird failed to find a positional Exchange sacrifice to maintain the advantage, and Blackburne liquidated into a promising endgame.

This development seemed to rattle Bird, who immediately dropped a pawn after refusing a Queen trade. His solid but passive setup allowed Blackburne to coerce Rook liquidation into an endgame, and we know enough about Blackburne's endgame technique to predict the result. The only real blemish here is his decision to trade Queens, as White has a pretty robust defence in the minor piece endgame, but Bird wasn't able to find it either. Better luck next tournament.

Round 5: Adolf Schwarz vs. Berthold Englisch

With this being the round in which two of our winners played, it makes no sense to show any other game. We saw their last game at Leipzig 1879 where Englisch won, and you would think that the two strongest players from Austria would have quite the rivalry (and you would be incorrect).

Schwarz repeated his first five moves from the third round, though Englisch opted to retreat his Bishop one square as he had done before. Schwarz's 10. d4 was ok, though it did invite many trades, and all eight minor pieces were off the board within the next five moves. The major piece endgame was technically better for Englisch, though both players had such ugly pawns that it was tricky to properly evaluate. His decision to open the f-file with 17... f5 was a very direct option, and while it forced Schwarz into the most passive defence known to man, it wasn't enough to create a win on its own. When Englisch offered to trade all the Rooks, Schwarz pounced on the opportunity, and they agreed to a draw with Queens and pawns only on the board.

These two would play twice more at the Vienna 1882 tournament, drawing their two games in 23 and 21 moves respectively. Like I said, not that interesting of a rivalry, unfortunately.

Round 6: Joseph Blackburne vs. Johannes Minckwitz

Welcome back Mr. Minckwitz. These two haven't played since Baden Baden 1870, where Blackburne won both games - one was a 95-move endgame grind, the other was a 21-move attacking masterclass. Which player had improved more over the last 10 years?

Blackburne had an affinity for the Van't Kruijs opening in this event, though unlike his previous game, this one didn't include any especially bad opening moves. One could argue that his decision to give up the Bishop pair on move 14 was bad, because it took his Knight a few moves to reach its desired outpost, but this didn't result in any serious issues. The closest it came to biting Blackburne was that Minckwitz developed his major pieces aggressively, but a trade of Queens made defending the attack much easier.

After a pair of Rooks also came off the board, we were left with a rather equal endgame with opposite-colour Bishops, though Blackburne was always going to push due to Minckwitz's bad pawns. He was helped by Minckwitz strangely giving up a pawn with 31... Bh5, an especially important pawn given that Blackburne already had a majority on that side of the board. Minckwitz offered little resistance after that, sacrificing a second pawn for less than nothing as Blackburne's King was given red-carpet access to the Queenside.

Round 7: Arnold Schottländer vs. Berthold Englisch

After Leipzig 1879, I knew that I had to include this game in the tournament regardless of the result, and I'm glad that it was so easy to slot in. Despite a mediocre performance in the tournament overall, Schottländer's victory over Englisch was very impressive, and so it's important to me to show off the return game.

I didn't initially intend to have a third 5. Nd5 Double Spanish already, but life is funny like that. Schottländer had the right idea with his 9. d4 pawn sacrifice, as Englisch is too solid to just positionally outplay, so an attack is warranted. Englisch had the opportunity to keep the pawn and really challenge Schottländer, but he ultimately chose to give it back in order to effect a Queen trade, as is customary. The resulting position with two Rooks and opposite-colour Bishops was technically equal, but surely Englisch was the happier of the two.

One principle that Steinitz had not yet drilled into everyones' heads was the concept of weak colours, which was very apparent in Schottländer's Kingside following the first time control. Englisch's King entered the White camp through the undefended dark squares, though it wasn't enough to create any objective advantage on its own. The players shuffled around for quite some time, with no progress to be made aside from one slip on Englisch's 35th move (which wasn't taken advantage of).

Scottländer was the one to make the crucial mistake, as his 42. b3 allowed Englisch's Bishop into the position and prevented his Rook from getting active on the a-file. The active Black King was suddenly a powerful attacker, forcing the pieces to make way for his Rook to infiltrate, and there was just no hope. Schottländer did find a slick resource in 59. Bg4+, but after Englisch correctly sacrificed the exchange, there was no saving this endgame.

Round 8: Victor Knorre vs. Adolf Schwarz

Knorre seemed to be quite active in the mid-1860s, with multiple short matches against Gustav Neumann and Adolf Anderssen, as well as a long match played in 1866 against Zukertort (which Knorre won 7-6). With no events to speak of in the 13-year gap, it's hard to say what kind of shape he's in.

Knorre preferred to revive the Exchange French for this game, which was livened up when he "sacrificed" a pawn with his 14th move. I imagine it was a pure blunder, but he did construct a Kingside attack that forced the players to walk a very narrow path. Schwarz missed a line that cemented his advantage, Knorre missed a line that promised a perpetual check; the madness was unrelenting. With Knorre threatening M1, Schwarz had to be more precise than ever with his counterattack - he chose the wrong piece to check with on move 25, and the resulting exchanges left him down a pawn in the endgame.

Had the endgame been played accurately, there's a real chance that this would've been among the finest games of Knorre's career. Alas, shortly after the time control, he fell asleep for one move with 42. Rxf7. Resignation occurred one move later, and the most chaotic game of the segment ended somewhat unfortunately.

Round 9: Berthold Englisch vs. James Mason

Following a rather disappointing campaign at Paris, Mason improved his play for this tournament - I don't know what his score was at this point, but he finished 5th overall so he's definitely playing better. His rivalry with Englisch is interesting, as they played 10 tournament games against each other and scored 8 draws, with Mason winning the other two.

Really the only reason I'm showing this game is because it's the only game from this round (assuming all dates are correct). It's an Exchange French that features a lot of exchanges, as is the norm for Englisch, but there's no follow-up endgame to speak of. Let's move on.

Round 10: Carl Wemmers vs. Joseph Blackburne

Wemmers finished in last place with 2/11 when we last saw him in 1879, and I have not learned anything new about him since then. He'll show up once more in 1-2 chapters, so I have one more chance to try.

I feel like we've been looking at an above-average amount of French games so far, and the trend continues here, though it's slightly varied with 2. Nf3 this time. Wemmers initiated three minor piece trades before giving a check, though Blackburne didn't need to castle anymore so everything was quite balanced. You would normally favour Blackburne against such an opponent, but he went wrong right at the first time control with 20... Qf7, ensuring that Wemmers would be the one playing for something. His Knight jumped around on the Queenside, and traded itself for the Bishop just in time for Blackburne's weak pawns to be pressured.

Always the professional, Blackburne adopted a passive, solid defense to prevent any breakthroughs. Although the engine will criticize, there were rarely moments that Wemmers could play for more than a slight advantage, and these weren't properly executed. Blackburne held the draw, which is good enough from the game's perspective, but probably not what he was looking for going into the round.

Round 11: Berthold Englisch vs. Szymon Winawer

Such a high profile matchup deserves to be shown, regardless of the outcome. One of Englisch's first professional scalps was his win over Winawer at Leipzig 1877, and we also showed his victory at Paris 1878, so these two have business to settle.

The players went for a different Spanish than usual for this game, with Englisch putting a pawn on c3 instead of a Knight. His opening was rather direct and aggressive, and he was rewarded with a golden opportunity when Winawer first gave up his Bishop pair, then allowed Englisch a rather standard sacrifice on g5. He didn't take it, of course, and gradually transitioned the game into a blocked position where he could claim to have more play on the Queenside. This was also not utilized at all, and once the Rooks came off the board, the rest of the endgame was straightforward. Englisch's games are, admittedly, not the most interesting, but thankfully I don't think he'll be the subject of any future chapters.

Round 12: Joseph Blackburne vs. Adolf Schwarz

Again, this game makes the most sense to show given that it involves two of the tournament winners. These two last played at Vienna 1873, where Schwarz actually won a game off Blackburne, though he lost their mini-match overall. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of their first four games against each other were French Defences, possibly making these two the world's two strongest practitioners in it.

The players repeated the opening few moves that Wemmers played against Blackburne, though Schwarz handled the Black pieces better, and Blackburne took many moves to finally plant a pawn on d4. Schwarz could have been more aggressive, notably missing a fine time to push f7-f6 and hit the strong White center. He was given a second chance after Blackburne's 15. dxc5 where he gradually built up minor piece pressure against the extended, somewhat isolated e-pawn.

Right around the time control, Blackburne again made his first major mistake, allowing Schwarz's Queen to actively place itself on b8 (which feels strange to type, but it makes sense). However, the Austrian once again missed a prime opportunity to open things with f7-f6, and had to settle for simply winning a pawn. While the resulting position was better for him, it wasn't enough for him to win, and Blackburne was allowed to escape with a draw. Yet another save for the Black Death, who keeps his positive record against Schwarz alive if nothing else.

Round 13: Emil Schallopp vs. Adolf Schwarz

I have to show two consecutive Schwarz games as round 14 is when Blackburne and Englisch duel, so here we are. Also, I'm still accepting access to Schallopp's book of the first two DSB congresses if anyone has any leads (that don't cost me an outrageous amount in shipping).

If you're not sick of the French Defence... how? Anyway, Schallopp actually had an edge in this game out of the opening, as he was allowed to win the Bishop pair while both players had an IQP. Although he lost out on this edge, he gained another as Schwarz failed to properly stake his claim on the e-file. By move 30, Schallopp had both Rooks on the open file, his Knight had a beautiful outpost prepared, and his Bishop was very active. It was as healthy a position as it gets.

Unfortunately, his move 30 advantage was thrown away by his slow move 31. With the initiative on his side, Schwarz fought against the strong Knight by doubling his own Rooks on the e-file (better late than never) and forcing mass exchanges. The resulting Queen endgame was very equal, and the two split the point. We've seen Schwarz going toe-to-toe with the strongest players in this event, and being able to save this game as efficiently as he did is also worthy of praise.

Round 14: Joseph Blackburne vs. Berthold Englisch

The two heavyweights finally clashed in the penultimate round, trailing Schwarz by half a point each. Schwarz would lose this round to James Mason, so a win for either player would give them sole first heading into the final round. Blackburne had to be considered the favourite, partly by reputation and partly by his 1.5/2 score over Englisch at Paris.

This was the second game where Blackburne tried 1. e3, which transposed into the Colle System harmlessly enough. Things became rather sharp with Englisch's 10... e5, where he gave himself an IQP that convinced Blackburne to give up the Bishop pair before sliding his Knight and Queen over to the Kingside for an attack. The spice was turned up to 11 when Blackburne sacrificed a pawn with 22. Nf5, forcing Englisch's sidelined Queen to make accurate moves as it was removed from the defence; when it didn't (27... Qb1), Blackburne won back his pawn plus another one, giving him a very promising position.

Unfortunately for the Black Death, even his endgame skills couldn't help him win the position following the Queen trade. Blackburne only had a light-square Bishop, and Englisch diligently put all of his remaining pawns on dark squares, maintaining an active enough Rook and King to ensure no (important) passed pawns could be made. A great save for Englisch, who at this point was the only undefeated player (Blackburne lost to Schallopp in round 11, and Schwarz lost to Mason in this round).

Round 15

At this point, all three gentlemen were tied for first place with 10/14, so choosing just one game to show feels wrong. Thus, we'll finish this chapter by showing all three games.

Berthold Englisch vs. Henry Bird

This game was possibly not the first to finish, but the first to be easily winning for one side. Bird went for the Elephant Gambit, but it resulted in neither a pawn sacrifice nor him getting an attack. After he allowed Englisch's Bishop to come to c4 with tempo, he missed how potent 9. Qb3 was, with checkmate being immediately threatened in such a way that he had to part ways with a Knight. He was finally able to castle on move 11, but being down a piece against Englisch isn't something one can ever hope to come back from.

Joseph Blackburne vs. Louis Paulsen

Louis wasn't having a very good event, as he dropped games against Fritz and Schottländer which left him on only 7.5/14 going into this round. It's been a while since these two last played, though their score at present was 3.5-3.5, trading wins across the decades at London 1862, Baden Baden 1870, and most recently Vienna 1873.

Unfortunately for Paulsen, this game was also not very good for him. It was he who adopted the less orthodox opening, though its symmetry up to move 8 makes it good enough in my book. One thing he struggled with was figuring out what to do with his Knight, as it bounced around e7-c6-e7 while Blackburne used his space advantage to properly position his pieces for a Kingside attack. Indeed, once he pushed f4-f5-f6, Paulsen was forced to resign under threat of checkmate or Queen loss. This was possibly the faster game of the round, but the mistake happened later so I think this position makes sense.

Adolf Schwarz vs. Carl Schmid

While these two are doubtlessly the least remembered players (I know nothing about Schmid), this game is the best of the three, and would be my pick if I had to choose only one game for the round. Let's look.

Schwarz gave us our first English of the tournament, which makes sense as it's something that is played today at the master level when a win is especially needed. Schmid increased this potential for a decisive result by putting pawns on f6 and h6, and though he initially was correct by placing his Bishop on h7 to guard them, he soon went astray by moving it to d3 and then off the diagonal entirely on c4. This occurred right at the first time control, and after the heavy-hitting 22. Ng6, Schmid gave up his Queen for a Rook and Bishop, giving Schwarz a massive advantage.

If this were the end of the drama, we'd be done, but it certainly isn't. Schwarz sacrificed a pawn to activate his Bishop, though this would have actually given Schmid a nasty counterattack if he took a second pawn. However, the problem was that Schwarz's plan in itself wasn't able to secure more than a draw, as his two attacking pieces weren't enough to give checkmate on their own. Schmid was able to make the second time control with the draw still on the table, but the position was at its sharpest.

Unfortunately for our unknown player, he went wrong with 41. Rc1+, as the check didn't actually accomplish anything except undefend his Knight. Schwarz used the resulting geometry to throw his Queen around the board, winning back his sacrificed piece and pawn and ending up three pawns to the good. Last-round exhaustion promises these types of games, and it was a lot of fun to go over, so I encourage you to do the same.

Conclusion

That crosstable looks much better, excellent. While it's not necessary, I included a tiebreak score (sum of scores of beaten opponents plus half the scores of drawn opponents) to conclude that Blackburne "won" the event. Englisch was the only undefeated player, though his tiebreak ended up being slightly lower than Blackburne's overall due to fewer wins against the top scorers. Schwarz suffered a little of both, incurring only one loss but picking up only one win against the top half of the field (but demolishing the bottom half better than anyone else).

This shared victory in such a large and impressive field should have further cemented Blackburne as one of the best players in the world, and added Englisch and Schwarz to the ranks of top-class players. It's also interesting that this tournament was slotted in between the first two German Chess Federation tournaments, which were won by Englisch and Blackburne respectively; perhaps I'll dedicate a chapter to Schwarz so that I can have balance.

Either way, I hope you enjoyed this somewhat unique post, we'll be back to normalcy right away.