Winner's POV: Vienna 1882 Part 2

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Vienna 1882: Steinitz Reclaims his(-ish) Throne

This is the second of my two-part coverage of the Vienna 1882 tournament; you can read the first part here.

To get us primed for this part of the tournament, here are the standings after the first half:

Before we dive in, I would like to mention that Josef Noa withdrew from the tournament at this point, and Maximilian Fleissig would withdraw after round 20 - both of these mean there will be byes for our subject, which will be addressed as we reach them.

The Winner*: Wilhelm Steinitz

As previously mentioned, Steinitz and Winawer were the joint winners of this tournament, and so this chapter will be dedicated to the future World Champion's games in the second half. Without further delay, it's time to look at the second half of the Vienna 1882 tournament from "the Winner's" POV.

Round 18: vs. Joseph Blackburne

If we look at the Vienna 1873 tiebreak, these gentlemen's 1876 match, and the first round of this tournament, we can see that Steinitz has won 10 consecutive serious games against Blackburne. Is this the world's first top-level adoption?

The last time Blackburne beat Steinitz (9 years ago, which feels somewhat depressing to say) was in a Nge7 Spanish. Although Steinitz delayed that move until move 4, Blackburne's plan remained the same: push d4 to relieve any central tension, then move everything over to the Kingside for some carnage. The games at Vienna lasted 27 and 28 moves, meaning that history really repeated itself here. Perhaps Steinitz should take a similar vow against Nge7 that Blackburne took against Bc4...

Round 19: bye

Steinitz got his first of two byes in this round, so it makes sense to check in on Winawer. He also played Blackburne in this round, and he also lost.

This isn't another Blackburne chapter, I promise.

Round 20: vs. George Mackenzie

This round would be very important for a handful of reasons. Mackenzie was both the tournament leader and the person who ended Steinitz's winning streak; beating him would both even the score and blow this tournament wide open.

The Queen's Gambit Declined is an opening that I wish Steinitz employed more often, less because it necessarily fits his own style, but because his opponents don't seem to properly know how to play the Black side of it. We saw it with Anderssen in 1873, and it's apparent here as well. Watch how quickly Mackenzie's position appears uncomfortable, and how he lashes out with an ultimately incorrect attack. It's a relatively smooth game for Steinitz, and a great way to bounce back and continue fighting as this grueling tournament continues.

Round 21: vs. Johannes Zukertort

The last time these two played a serious game was in 1872, where Steinitz won their match (+7-1=4). Of course, it's fair to say that Zukertort was not yet at his full strength, as he wouldn't come into his own until the later part of the decade. With his win at Paris 1878, match win against Steinitz's previous rival Blackburne (+7-2=5), and Zukertort's win in their first game of this tournament, it was clear that a match between them now would be much more interesting. But that's for another time.

The Steinitz Variation of the Three Knights was on the table for this game, an opening the man himself would opt for a grand total of 5 times during this tournament. This game was a very good showing for it, as after Zukertort's unnecessary f2-f3 (probably setting up a g2-g4 push and a resulting Kingside attack), Steinitz was able to break in the center and establish an annoying initiative. He cashed in on this assault by winning a pawn and doubling the pawns in front of Zukertort's King, but the counterattack was very difficult to properly defend.

The most critical moment of the game came shortly after the time control (which doesn't happen very often, but here we are), where Zukertort won back the pawn but allowed all of Steinitz's pieces to gang up on g2. One move stood between losing and drawing, and Zukertort chose incorrectly. However, I think Steinitz rushed his attack a little, as he gave a premature Rook check that allowed the White King to escape. The players agreed to a draw rather than play out the double-edged Rook endgame, putting an end to a very complex game for only 36 moves.

Round 22: vs. Vincenz Hruby

At 9.5/17, Hruby was the highest scoring local at the end of the first half (if you exclude Englisch, which I am). He got there partially through defeating Steinitz in their individual encounter, meaning he's not someone to take lightly.

Steinitz returned to his Romantic roots with a King's Gambit for this game, though his Queen trade on move 7 was not one that would be repeated ever. He must have missed how strong Hruby's 9th and 10th moves were, which ultimately won the exchange for the local player. Steinitz isn't one to shy away from a fight, and he spent the rest of the middlegame trying to attack in his own, unique style.

The time control was Steinitz's best friend here (for a number of reasons, if you recall the round 4 ordeal from the previous chapter). Hruby's decision to exchange on move 29 allowed him to make the time control safely, but it left him with a position that couldn't be better. When he outright blundered on move 43, suddenly Steinitz had a winning tactic, and the champion executed. This game is really impressive all around, and was one of my favourites to go through the first time when I was planning this chapter; hopefully you enjoy it as much as I did.

Round 23: vs. Preston Ware

Had I not looked at anything else before this tournament, I would have been confused why Preston Ware, a rather average American player, was playing in this extremely strong tournament. However, given that he also defeated Steinitz in their first encounter, I suppose his place here isn't too out of place. Steinitz's first half of this tournament was turbulent, to say the least.

This game, on the other hand, is about what you'd expect. Ware lost his Queen less than 20 moves into the game, and prolonged it all the way to checkmate. I don't want to linger here, let's keep moving.

Round 24: bye

Steinitz's second of two byes occurred in this round, so it's back to Winawer we go. Here he played his second game against Chigorin, defeating the young Russian with the black pieces.

Round 25: vs. Alexander Wittek

Wittek was the fourth and final person to defeat Steinitz in the first half of the tournament, giving the champion a 3.5/8 score up to that point. Of course, Steinitz then proceeded to win seven of the remaining nine games, but that doesn't matter much to Wittek. The architect would win games against Mackenzie and Englisch in his final tournament, wrapping up a short but solid career in very respectable style.

Unfortunately, this game isn't one I'd have liked to put as the gentleman's final game. His 19th move just blundered the Queen, but unlike Ware, Wittek at least didn't drag the game out for longer than necessary.

Round 26: vs. Philipp Meitner

The only thing I'd like to say about this game is that at least Meitner had the decency to resign this game, instead of just abandoning it after the lunchtime adjournment (see the previous chapter, round 6 for context).

Round 27: vs. Mikhail Chigorin

As far as this series is concerned, this is the only game between these two that we'll be observing. Steinitz won their first game in this tournament, as was likely expected, but Chigorin would win both of their games at their next tournament (the last before their first world championship match). In between their two matches, they only played two more games, and both were won by Chigorin. As far as tournament results are confirmed, Chigorin had a lifetime positive score against Steinitz, and today we witness the start of that tremendous achievement.

Chigorin's weapon against Steinitz in the vast majority of their games was the Evans Gambit, and Steinitz chose to answer this with 5... Bf8, an even more dubious option than the one he played against Blackburne in '72. The sequence of the game felt quite logical: Steinitz's King was stuck in the center, so Chigorin put all of his pieces in view of the center; when Steinitz finally castled, Chigorin forced him to accept a bad pawn structure; when Steinitz returned the pawn to finish development, Chigorin found 18. Nd6 to keep the initiative.

Move 21 was the turning point, where Steinitz felt compelled to sacrifice his two Bishops in exchange for Chigorin's Rook and the initiative. This turned out to be incredibly incorrect, as Steinitz's threats were methodically blocked, and his Rook's influence was made very minor. Once the tricks were all gone, Chigorin could enjoy his material plus and dutifully converted it. This is such a pretty game, please look over it and enjoy.

Round 28: vs. Max Weiss

Weiss's first half wasn't all that great, as we saw his catastrophic loss against Winawer, as well he was on the receiving end of a very model game from Steinitz in their first encounter. His second half has proven to be better, as he held Winawer to a draw in their return game. What of this pairing?

This game initially followed the Blackburne - Steinitz game at the start of the chapter, with Steinitz's move 11 deviation being a good one, but not a novelty - Meitner had played the same way in an earlier game against Weiss. Steinitz was rewarded for getting his two Bishops on the long diagonals, first pushing on the Queenside before setting up a checkmating battery pointed at Weiss's Kingside King. The momentum was on his side early, and it was incredibly hard to take back.

Weiss, very pragmatic lad, assumed the defensive and held off his formidable opponent. Although it wasn't perfect, he found a way to trade pieces just in time to force an equal endgame. Were the White pieces played by a more experienced opponent, I hope Steinitz would be satisfied with forcing a rather comfortable draw; here, I can imagine his cursing that he couldn't find a way to get an extra half point.

Round 29: vs. Szymon Winawer

With Mackenzie's second half not doing so well, the battle for the top spot was most closely contested by Steinitz, Winawer, and James Mason, the latter of whom won his second game against Winawer two rounds prior to this. This game is, unsurprisingly, quite crucial.

This game started as one of those typical Steinitz games from the previous decades, where he plays a dubious opening that results in his King going for a walk. We've seen in previous games, for example Steinitz - Neumann 1867, where Steinitz's position is perfectly playable once his King escapes the danger. This was nearly the same case here, with Steinitz very nearly being dead lost until move 25, where Winawer's refusal to play a Queen sacrifice that would put both Rooks on the seventh rank allowed Steinitz to complicate things in time trouble.

In the moves following the time control, Steinitz had regained the initiative and Winawer had to cope with the fact that his attack had been ended prematurely. He didn't, instead allowing his Knight to be lost in exchange for a (very brief) attack on Steinitz's King. The problem with this was that it allowed Steinitz to also open up Winawer's King, with a much more problematic attack. While the game could have ended in Steinitz's favour, finding the correct checks to give proved to be easier said than done, and the players ultimately agreed to a draw once Winawer's King escaped and the result was up in the air. Crisis averted for both.

Round 30: vs. Berthold Englisch

This sure was a game alright, yep, definitely.

Round 31: vs. Adolf Schwarz

While I still believe that Schwarz is one of the stronger players of his time, this is really the super tournament to end all super tournaments, so his middling performance is reasonable. I'm glad I was able to make at least one (plus a partial) post on the man.

This game was about as one-sided as any, sadly. Schwarz elected to castle Queenside, but Steinitz was the one doing all of the attacking. Once Schwarz traded into a Knights vs. Bishops middlegame, observe how methodically Steinitz restricted the squares of his opponent's Knights while gaining space, not-so-slowly squeezing the position while advancing the pawns until the breakthrough occurred and the White King was toast. It's a good day when Steinitz's positional principles allow for a strong attack as well.

Round 32: vs. James Mason

Mason was only a half point behind first place, so again, this game is a crucial one. Having so many important games at the tail end of a 30+ round tournament must be equal parts exciting and exhausting.

The prime imbalance was made quite clear early in the game, with Mason's pawn structure being damaged on his Rook's files, so he was to take the role of the attacker. Steinitz took to the Queenside, and his Queen on b6 was especially well-placed for targeting the weaker pawns in Mason's camp. It was quickly clear that Mason had no attack to speak of, and his position was passive, ugly, yet defensible.

Right at the time control, Steinitz recaptured a pawn on f6 with the wrong piece, and Mason found a path to simplify. Although Steinitz was in possession of an extra pawn, it wasn't enough for an advantage as Mason's remaining pieces were still on the Kingside. The players shuffled for many moves, and while Steinitz was lost for exactly one move, the players ultimately made a draw at the end of another intense game. But had Mason found that one move, we'd be looking at a completely different chapter.

Round 33: vs. Louis Paulsen

After 25 years of coverage, we're looking at Paulsen's last tournament appearance outside of Germany. He would still compete in a few more German Chess Federation tournaments that we'll be covering, but this event would be his last trip abroad. Steinitz had previously said that Paulsen's defensive play had partially inspired his own school of thought, and now these two indirect collaborators will clash for the final time.

The Steinitz Variation of the Scotch is one that can be very uncomfortable for White to deal with if you don't know the theory, which is obviously the case here (since the theory doesn't exist yet). For example, 6. Be2 is better than Paulsen's Be3 as the notes explain, and so Steinitz was able to escape the opening with a (mostly) healthy pawn. What followed was a very bizarre sequence of events, however. When Paulsen started pushing his Queenside pawns up the board, Steinitz responded by doing the same, weakening his King's cover. He even dropped a full pawn (a very, very important one at that) to a simple tactic on move 21, but after Paulsen missed it, things took a turn.

Really, following that tactical miss, things never got better for Paulsen. He was able to regain his lost pawn, but the endgame he traded down into was much worse. He was slowly ground down, not being saved by any of his piece trades, until all that was left were Kings and pawns - both of which were better for Steinitz. This would be Steinitz's sixth consecutive, but final, tournament win over Paulsen, after conceding only one loss back during London 1862.

Round 34: vs. Henry Bird

One thing I've not talked about during any of Bird's appearances in this series is his health. Bird suffered from gout, which is an intense and painful swelling, usually in the joints. The gout attacked during this tournament, causing Bird to sit out the previous five rounds and effectively withdrawing. However, given that first place was on the line, he elected to play out this final game, despite clearly being unwell. For this reason, I've decided not to annotate the game, as it'd feel wrong to talk about any mistakes for a game played under such conditions. I think I need to show a little respect to Bird after his previous showings, and for this level of sportsmanship.

Conclusion?

This crosstable was never going to be readable.

The important part is that Steinitz and Winawer tied for first, as previously explained. Mason finished third, one point behind them (recalling the Mason-Bird episode of round four, that game played an astronomical impact), while Mackenzie and Zukertort tied for fourth - Zukertort won an extra prize for having the best score against the top three.

With all that behind us, it's time for the grand finale.

Tiebreaks

The first game is perhaps among the first examples of targeted opening preparation - knowing that Steinitz had been playing his novel 2. e5 French all tournament, Winawer prepared 2... f6 as suggested by the Frenchman Samuel Rosenthal. Something tells me that the players were still on their own rather early, however, especially after Steinitz's 7. Qd2 allowed Winawer to pick up four points of material in exchange for defending a rather serious attack. The position after Steinitz's 13th move looked like a textbook sacrificial attack, and when Winawer blundered, Steinitz went for it all: he sacrificed his other Rook (in the style of the Immortal Game).

Both players had to play specific moves in order to maintain the balance, and the first one to deviate was Steinitz. Had he played 17. Ne4, he quite possibly would have played the greatest game of the tournament; 17. Qd4 was unfortunately just a misstep that allowed Winawer's Queen back into the game, and once the attack was parried, the material deficit was obviously too much to overcome. I propose we dub this the "Mortal Game."

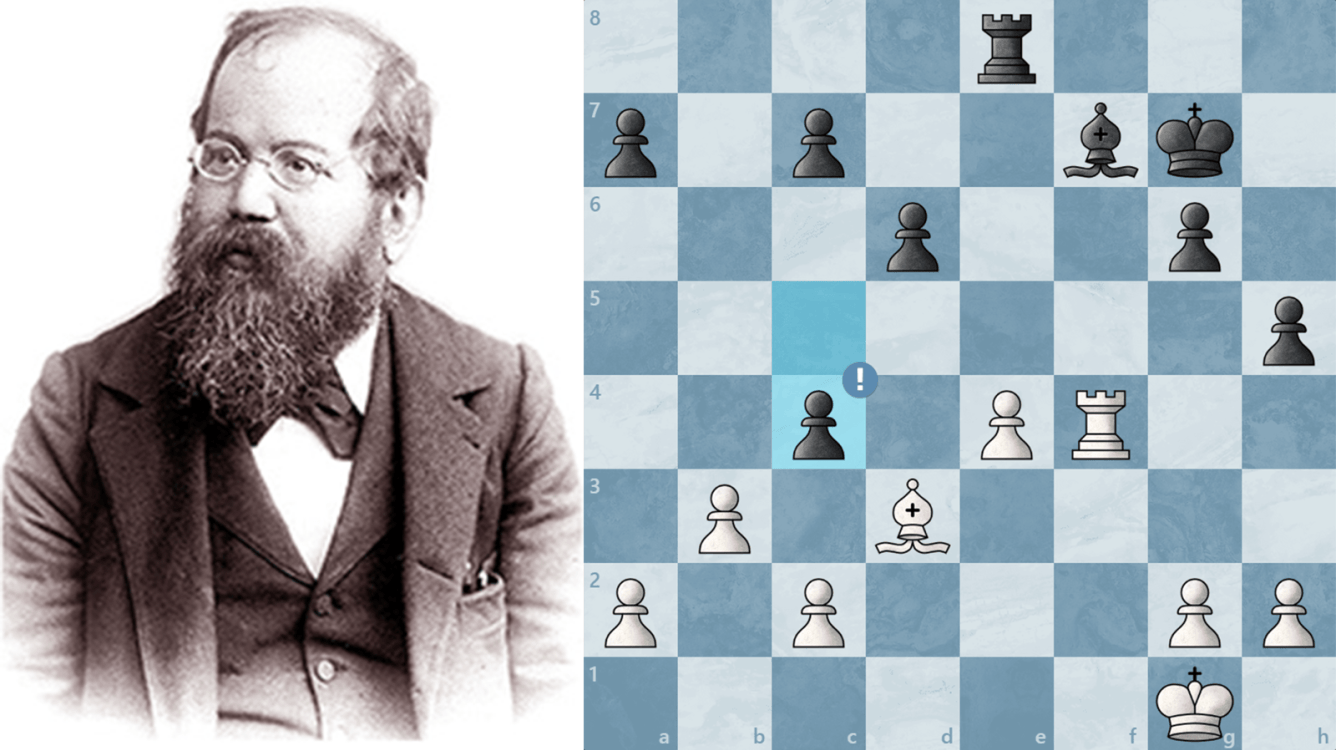

The second and final game, I think, is much more interesting to talk about. In the final Steinitz Variation of the tournament (the Three Knights one this time), Winawer showed how cautiously he was playing, trying to ensure he could draw his way to first place. His 14th move especially made this task more difficult, as it forced him to go on the attack to compensate for his problematic pawn structure. His biggest chance to put Steinitz to the sword was on move 19, but when he refused to play the pawn break and instead went for trades, things took a turn.

Steinitz showed how much further he had seen than Winawer when he allowed the Queen trade before playing 28... c4, giving him the slightly better endgame he desired. This endgame would be played until bare Kings if it needed to be, though Winawer's play was very poor at this point; he put his pawns on the wrong colour before swapping off Rooks, making Steinitz's path to victory very easy. However, after well over a month of grueling tournament play, I don't entirely blame Winawer for crumbling like this. At least this one didn't cost him the tournament.

At long last, after about a month and a half of play (and many months of writing this mammoth), the tournament ends with joint winners. Steinitz reaffirms that he is quite possibly the strongest player on the planet, while Winawer rights his wrongs from Paris and survives the tiebreak. The 1880s are off to a tremendous start, and things aren't slowing down (in terms of size, either...)

Next post will be much, much shorter.