Winner's POV Chapter 26: New York 1880

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 26: Fifth American Chess Congress (New York 1880)

If you've read the previous ACC chapters, it should hopefully not come as a surprise that I have a general disdain for the way they've handled certain things. The third ACC had no tournament book, while the fourth had one with very lackluster writing and annotating. Another issue was the prize fund, with the first ACC still offering the best prize after three subsequent tournaments. This edition does improve in those regards, as its tournament book ended up being the replacement tournament book for the last two, and the prize fund was massively improved. On this front, I have no complaints.

There are two things that marred this tournament more than most others in this saga: bad games and a very serious potential cheating accusation. GM Andy Soltis writes the following in The Book of Chess Lists:

"The 5th American Chess, held in NY in 1880, was a weak tournament and produced both a poor tournament book and an atrocious series of games. It is forgotten except for an incident in the final round..."

While I don't necessarily agree with his opinion on the book, I can attest that going over some of these games was more annoying than usual. We'll be focusing on a very strong player, so most games do have a reasonable quality on his part, but there are still a large quantity of bad games. The cheating portion will be addressed at the end, as it occurred in the final round, so let's get there as quickly as possible.

Format and Prizes

This was a 10-man double round robin, with a time control of 15 moves per hour.

The prizes at last were upgraded significantly, as mentioned in the tournament book:

$500 in 1880 would be worth approximately $15,000 today, which is a very decent purse. Until now, the $300 offered in the 1857 ACC was the highest, with a current value of about $10,500. At last, America is making progress.

Players

The 1880 Edo lists give the top of the field as George Mackenzie (5th), Max Judd (14th) and Charles Möhle (21st).

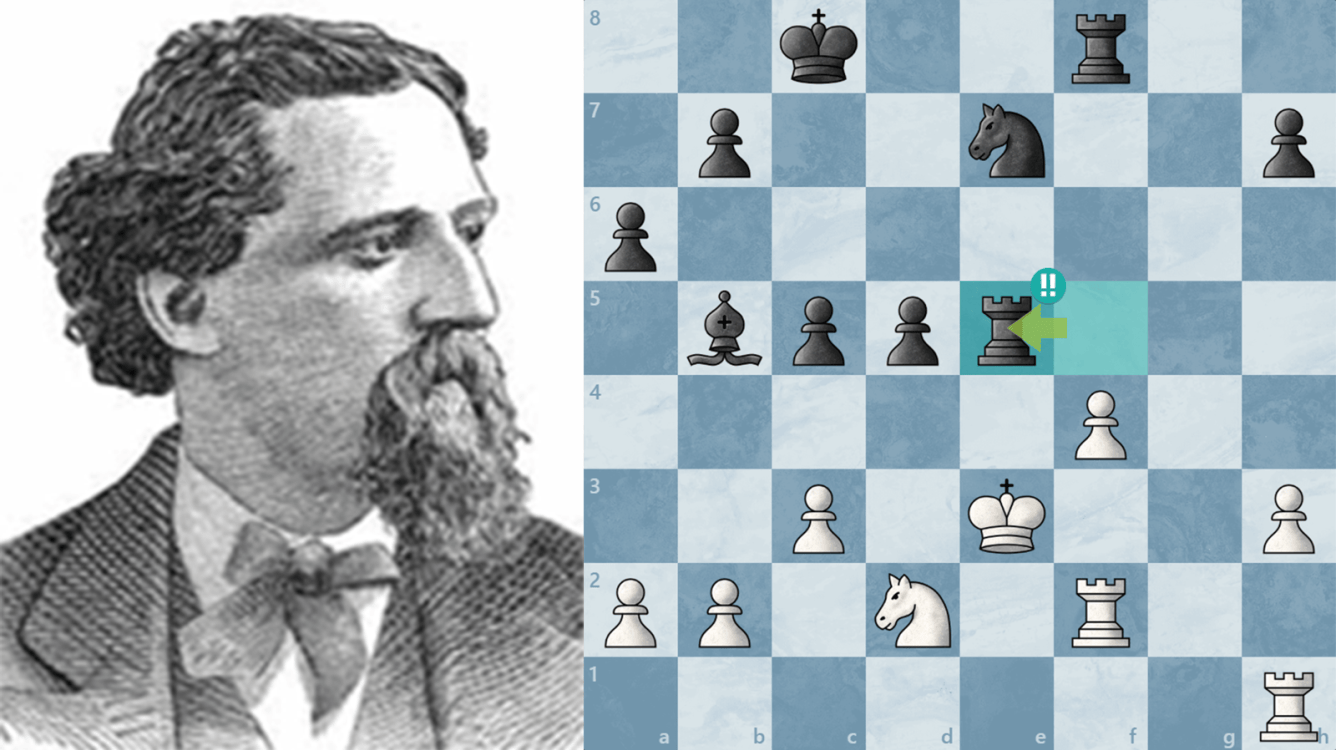

The Winner: George Henry Mackenzie

This would be Mackenzie's third ACC win in three appearances, and his last overall. Following this, he would transition to playing in exclusively European tournaments, and we'll be seeing him regularly starting in 1882. Given that he didn't play in the 1876 edition, it makes sense that he should reclaim his title before his departure. Thus, we'll be following Mackenzie once more as we explore the Fifth American Chess Congress from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. Albert Cohnfeld

I could only find one other event in which Cohnfeld played, which was a tournament in 1876 named the "New York Clipper Tournament." Cohnfeld scored only 3/15 in that event, which was ultimately won by James Mason.

The opening was a bad one by Cohnfeld, who was down in development from the outset. Things didn't improve after he blundered a piece on move 12, giving us our first bad game of the day.

Cohnfeld allowed Mackenzie to play a Spanish, which we've seen him do very well in. This version ended up being very non-competitive, as after Cohnfeld's 9... c5, he was permanently worse. I didn't end up commenting on this game too much, since I don't think it's very good, but you can judge for yourself.

Round 2: vs. James Glover Grundy

During the Paris tournament, I talked about how there was supposed to be a match between Joseph Henry Blackburne and Johannes Zukertort in 1877, but the match was cancelled due to Blackburne's side being unable to pay the stakes. Grundy was responsible for these stakes, as the backers were primarily from the city of Manchester and Grundy was the Secretary of the Manchester Chess Club. Following this failure, Grundy moved to New York, where he found himself at this time.

A few weeks prior, Mackenzie had beaten Grundy 2-0 at the odds of a pawn and move, so the expectations were rather low for Grundy in this series. He held his own in this game, with things being rather balanced until Mackenzie's 23... Rad8, which handed Grundy the open a-file. Rather than apply much pressure, he chose to liquidate into a better endgame, which turned out to be a rather strong idea given the exact endgame these two settled on.

The critical moment came on move 36, where Mackenzie had to sacrifice a pawn in order to further simplify into a Bishop vs. Knight endgame where he could hope to draw. When he instead advanced his King, he clearly did not fully appreciate the power of 39. Bd5, which created a potent checkmate threat. Mackenzie had to part ways with his Knight in the process of defending it, and the game was over. A very shocking result, and one of the many examples used to suggest Mackenzie was playing below his full strength for this tournament.

Grundy employed a French for the return game, which led commentators to claim he was playing for a draw from the beginning. The frustration Mackenzie was feeling was palpable, and it showed in his play as he doubled Grundy's Kingside pawns and threw his own up the board. Grundy held his own once again, defending accurately for the first 20 moves or so. The cracks started to show however, with move 22 being the one I chose to focus on, but there was no clear win.

Mackenzie had been setting up a sacrifice on h7, but he released it at the wrong time. Grundy had an identical tactic at his disposal, and when both were executed, the resulting position was a dead draw. This was a monumental result, as Grundy had taken the lead with the strongest player in the tournament dealt with. The tension was immediately sky-high.

Round 3: vs. Preston Ware

This is the tournament in which the Ware Opening and Defense got their names; Ware played 1. a4 twice, and 1... a5 in all nine games at this tournament. He understandably didn't score well with it, though he did manage a win against Grundy, which is important.

This game started with what looked like a Scandinavian where Black played 4... a5; obviously this isn't a very good departure from theory, and it's hopefully unsurprising that the novelty occurred as early as move 5 (and the other game was one that Ware played in the previous round). That's really the only thing of note, because Ware's play didn't really improve into the middlegame, and Mackenzie didn't do too much to refute the weak play. He still won, of course, but hopefully you're starting to agree that the quality of play is unusually low here.

Ware preferred 1. d4 in his White games, so the players engaged in a Dutch for their encore. The novelty was again early, and again deviating from another Ware game, and again the result was unchanged. Ware's pawn play was especially bad, notably 9. a4 and 11. b3 were unnecessary moves, the latter of which further stalled his already-suspect development. This was another weak game, but it did provide us with our first brilliant move of the event, so there's that.

With nine rounds, it makes sense to look at the standings after the first three. Consulting the tournament book:

Both Grundy and Sellman were undefeated up to this point, which is important to point out given the next round's pairing.

Round 4: vs. Alexander Sellman

Some sources dub Sellman the unofficial "Champion of the Southern States," but he's from Baltimore. Is Maryland considered south? In any case, I have to show some gratitude towards this man, as he wrote the only contemporary tournament book to an event I'll be talking about in one of the next few chapters.

Facing another French, Mackenzie opted for 2. c4 and threw theory to the wind. The first few moves were taken out of games from the London 1851 tournament (which had numerous examples of very sketchy opening play), and after Sellman's well-timed 10... d5, he was certainly better. But this was the price Mackenzie was willing to pay: he gets a bad position, but one that he can outplay his opponent in.

The position was never so bad that Sellman had a decisive advantage, but it did allow him to safely trade down into a risk-free endgame. However, as we've seen before, the tone of the endgame can be leagues different with pieces vs. with bare Kings (remember Paulsen - Englisch, 1877?). That was the case here, as Sellman's decision to trade Rooks actually left him with a worse King and pawn endgame.

As Mackenzie advanced his King and the players tried to jostle for key tempi with their pawns, the endgame was eventually completely winning for him. As we've also seen before, one move makes all the difference, and in Mackenzie's case that one move was 44. h5. He correctly analyzed the proper 44. g5 in his annotations, but that wasn't enough to save him from dropping this half point. Had he won, I would be drawing parallels with our own time's GM Magnus Carlsen insofar as his decision to play a strange opening and decide things in the endgame. Alas, here we are instead.

Sellman opted for the Mackenzie Variation of the Spanish in the return game, which makes a certain sense; if the player believes it to be a good attack, he must have some argument against its defense, right? Well Sellman didn't exactly play it like Mackenzie would, as he traded his Bishop on c6 to regain the sacrificed center pawn. He elected for a few more trades early, destroying Mackenzie's structure and trying to steer things toward an endgame.

It was Mackenzie's turn to incorrectly enter a particular endgame, as he was much worse once his Bishop pair was removed. The weak Queenside pawns would be hunting grounds for a modern master, and someone like Berthold Englisch would probably have been delighted to play such a position. But Sellman's plan was to adopt a simple checkmating attack, and Mackenzie was able to defend this while basically forcing a repetition.

Round 5: vs. James Congdon

It feels good to finally be able to post a portrait of someone. Anyway, we missed Congdon at the third ACC, as he withdrew in the final round before he could face Mackenzie. But the most important thing I want to share about this guy is a game he played in the next round against Eugene Delmar. With Congdon down five pawns, see if you can find out how this game ended.

Anyway, back to the tournament games we'd actually like to focus on. Mackenzie returned to normal French theory in this game, though the same could only barely be said for Congdon, as his 9th move was a departure from theory and chess principles as a whole. His 9... f5 permanently locked down the center, and gave Mackenzie a space advantage that acted as a green light for a future attack. We know Mackenzie, so it should come as no surprise that he began working singularly toward this end.

One thing that we appreciate more nowadays is that an attack doesn't necessarily have to end with checkmate or a material plus; often it's enough to just force matters into a superior endgame. Mackenzie missed such an opportunity on move 32, where he could've traded his Knight for three connected passed pawns that would've decided the game. He did play it two moves later, but Congdon was given enough time to improve his position, and neither the attack nor the endgame was actually there anymore.

In an effort to play on, Mackenzie actually ended up on the worse side of the resulting endgame, as his two pawns were not enough to compensate for Congdon's Knight. It was far from a sure thing, however, and we've seen how uncertain endgames can be. It took almost 30 more moves to decide things, but Mackenzie was able to salvage half a point from this absolute mess of a game.

Mackenzie switched to the Berlin for this game, though we had a novel position as early as move six, so it was hardly an orthodox one. This game featured the thing that earned him two previous ACC titles: pushing Kingside pawns and attacking the King. Congdon adopted the correct response by pushing on the Queenside, but one threat was much more potent than the other, with Mackenzie having two Rooks on the open g-file staring menacingly at the ivory monarch.

The critical moment came on move 34, where Congdon had to put all of his faith toward his Queenside pawns and make them passed. While it's an understandably difficult decision to make, his 34th move instead allowed Mackenzie to fork his Knights, dropping a piece for nothing. After being deprived of a win for three straight games, I'm sure this felt good for Mackenzie.

Round 6: vs. Charles Möhle

Chess seemed to be a staple in the Möhle family, as Charles's father Adolphe Möhle was an active player in the 1850s - he placed 2nd at the New York Chess Club Championship of 1855, and entered into the minor tournament of the 1857 ACC. Charles would follow in his father's footsteps, as he would also play in a few more American tournaments, as well as operate the chess automaton Ajeeb in the later part of the decade.

We return to the "trade twice on e5" variation of the Four Knights Spanish for this game, where a hasty f4 thrust from the young Möhle simply dropped a pawn. While he did have the Bishop pair in exchange for this loss, he didn't get to use it for much, as his tricks were easily parried by the experienced Mackenzie. There were basically no serious problems posed for him as he gradually converted, and he even got to throw in a nifty Knight "sacrifice" on move 24.

I imagine that being held to three consecutive draws against the French influenced Mackenzie's decision to play 1. d4 in this game, and so the players explored a Dutch instead. Möhle's 4... c5 made things look like a weird Benoni, which certainly helped if his goal was to get the ex-Captain out of book. The center was again locked, and Mackenzie used this structure to once again justify a Kingside attack after Möhle's King castled that way.

After Mackenzie castled Queenside, it looked like his attack was ready to begin. However, he seemed to miss how powerful it would have been to plant one of his Knights on the e6 outpost; when he refused, Möhle was allowed to counterattack on the other flank. By the time Mackenzie adopted the Knight outpost plan, Möhle struck first, establishing his own Knight outpost on d4 and actually putting Mackenzie on the defensive. This was not the same Möhle we saw in the first game.

After the Black Rook infiltrated along the semi-open f-file, Mackenzie made a critical blunder in defending his own Knight. He allowed the Black Queen to enter via the Queenside, and in the process of protecting against checkmate, he parted ways with the same Knight he tried to defend. An incredible victory for the 21 year old Möhle, and a sign to Mackenzie that he apparently needs to get his act together if he wants to win the tournament.

Given that Mackenzie had some catching up to do, this subpar segment surely didn't help him all that much. Let's take a look at the standings up to this point:

Grundy's lead has increased by another 1.5 points, putting Mackenzie in an even bigger hole than earlier. With six games remaining, closing a two point gap is far from insurmountable, but there's a lot of work to be done. Let's keep going.

Round 7: vs. John Ryan

Ryan's records are scant and largely unimpressive: a 1-6 score against Henry Bird in 1876, and a 4/13 score in the New York Clipper tournament of the same year. He apparently had some success with the Manhattan Club championships (the same club that hosted this event), winning it in 1884 and 1886.

This game should technically be classified as a Pirc, which likely gave Mackenzie much more hope than the Frenches he had thus far been facing. Also helping his cause was the number of bad moves made by Ryan, with the standouts being 4... Bh4+ and 8... Nc6, with the "losing" move of 24... f6 being played in a position where he probably wasn't going to survive anyway. This was just an absolute steamroll, the kind we're used to seeing from Mackenzie.

Mackenzie sat on the Black side of the Dutch for this game, a decision I wholeheartedly agree with (I felt the same about Adolf Anderssen, in that he really shouldn't be playing 1. d4 as White at all). While the opening itself was much more measured, it still felt like Ryan was rushing toward disaster with 12. d5, dropping a pawn. However, it turned out to not be too awful, as Mackenzie's extra pawn was backwards on a semi-open file. It's my non-professional opinion that this position is a textbook example of "dynamic equality."

As the players tried to navigate the very complicated middlegame, it was actually Mackenzie who made the first major mistake with 24... d5, the same move that Ryan misstepped with earlier. This move cost the exchange, and when the trades were completed, Mackenzie had an objectively worse position. It was one that would certainly take a lot of time and effort to win, especially with such a tricky player as Mackenzie, who refused to concede ground for another 30 moves after the exchange was won.

The decisive mistake came on move 57, where Ryan spoiled a great position by walking into a Knight fork. If he allowed Mackenzie to win back the exchange, the endgame would have been trivially drawn; inexplicably, he chose to give up his Bishop, and the resulting endgame was actually lost for him. After this complete 180, Mackenzie had no issues converting the endgame, where his two pieces overpowered the Rook as his passed pawn ran up the board. The chess gods were smiling upon Mackenzie this day, apparently.

Round 8: vs. Max Judd

What would an ACC chapter be without our good friend Max Judd? At this point, these two players shared second with 10 points, a single point behind Grundy's 11. In this series, Judd has scored 0.5/5, so he needs to do what he's never done before in an ACC: beat Mackenzie.

Yet another French was on the table, though Judd should have looked at Congdon's game before this, as his deviation on move 7 was a bad one. What transpired was like an improved version of the trap in the Szén Variation of the Sicilian, where Mackenzie planted a Knight on d6, deprived Judd of castling rights, and messed up his pawn structure by deleting the Knight on a6. The engine gives an evaluation of +2.5 on move 10, which is just something you can't allow in such a crucial game.

As the game went on, Mackenzie somehow failed to generate enough activity before Judd was able to remove his weaknesses. While Mackenzie tried to push on the Kingside, Judd was able to trade off the strong Knight on d6; when Mackenzie opened the Kingside to attack, that allowed Judd to trade off his inactive Rook. There ended up being no attack, and Mackenzie correctly repeated moves instead of pushing for anything more.

I don't know why, but the annotators insist on calling this the Scotch Gambit rather than the Game, but that's a minor concern. Despite playing the opening three times in this event, it was actually Judd who erred first with 9. f4. Mackenzie's response of 9... Ng4 was given two exclamation points by the engine, and it makes sense; the resulting sequence left Mackenzie with better development and the safer King. Even in a middlegame with a super early Queen trade (move 11), Mackenzie was well-poised to go on the attack.

Mackenzie did everything right on a fundamental level: he pushed the correct pawns, traded them off to open up lines, and increase the vulnerability of the opposing King. While the defense for Judd was certainly possible, he made the critical mistake on move 26, moving his King the wrong way. Mackenzie punished this in the way we always expect him to, getting a second brilliant move that I've put as the banner for this chapter. Better luck next time, Judd.

There's a lot to talk about in the last round, both directly and indirectly concerning the chess. For added context, let's look at the scores after round 8:

There are three crucial matchups in this round: Grundy vs. Ware, Judd vs Möhle, and the one we'll be looking at directly. Let's talk about what happened.

Round 9: vs. Eugene Delmar

This guy has games going back to 1859, featuring some matches and a lot of New York club tournaments with the usual scant documentation. His most significant result is a 2nd place finish in the aforementioned Clipper tournament in 1876. I also found a bunch of games he played at various handicap odds against Mackenzie in 1870, with the overall score being 34-37 against him. How would he do with ten years of practice without odds?

Delmar was clearly not paying attention to previous games, as he pushed the King's pawn one square too many on the first move. In the Steinitz Defense of the Three Knights, both players pushed the f- and g-pawns in front of their Kings, promising Kingside attacking potential to whoever could seize the initiative. That proved to be Mackenzie, who planted a Knight on e6 to win the Bishop pair, solidifying his advantage.

Things seemed to progress very logically for Mackenzie, who doubled Rooks on the f-file, pushed f4-f5, and opened up the Black King. Delmar really didn't put up much resistance, dropping a full piece on move 22 while still having the worse development. Very little drama in this game, but the tournament as a whole could not be more different.

Also in this round, Möhle beat Judd and Grundy managed to lose against Ware. There was a three way tie for first place, which meant the drama going into the final day of play was as high as it's ever been.

Delmar gave us our first look at the English for this event, though he didn't handle it very well: he brought his Queen to b3, but then still allowed his pawns to be doubled and his Queen to be trapped behind them. It was hardly an inspiring opening, but it wasn't as bad as some others. As per usual, any opening errors can have their damage mitigated if you're aggressive enough, which probably inspired Delmar to thrust forward with 14. f4. He doubled on the e-file, opened up that file, and had about as good a position as he could hope for.

The professional Mackenzie encouraged both pairs of Rooks to be traded, and the resulting position was quite equal, if not slightly better for Black due to the pawn structure. However, in an attempt to really put pressure on Delmar, Mackenzie played the nifty 28... b5, fixing the structure in exchange for ensuring his Bishop was the better of the two. This ended up being a genius decision, as Delmar had absolutely no idea what to do with his depressingly passive pieces. Mackenzie steadily advanced, infiltrating the position with both his Bishop and Queen to really make Delmar's life difficult.

As always, the exact technique in this endgame (or middlegame?) can be critiqued, notably Mackenzie missing a strong shot on move 41. When he found it on move 43, it was still good enough to win a piece, and eventually force resignation. For those keeping score at home, you'll see that Mackenzie scored 5.5/6 in this last segment, finally reminding everyone why he's the best player in the USA by a wide margin.

The other two games went on for many more hours, and naturally attracted many more spectators. Möhle and Judd drew, putting Möhle half a point behind Mackenzie, but that's not the most important piece of trivia. In the game between Grundy and Ware, the story goes that Grundy offered Ware money to play for the draw, therefore guaranteeing Grundy at least second place. The problem was that Ware had a totally winning endgame, so playing for the draw was quite difficult. At some point, he even made a losing blunder, allowing Grundy the opportunity to win the game and tie Mackenzie. I'll let you all look at the game, and see if anything suspicious pops out at you.

The committee wasn't able to confirm or deny anything, as it basically turned into a "he said she said" situation with Ware admitting to it and Grundy denying it. They declared Grundy not guilty, and with that the final scores were as follows:

Tiebreak: vs. James Glover Grundy

After multiple weeks of play, both players were very tired, and it shows. In this first game, Grundy tried to castle Queenside, but he gave up a pawn because of it. Mackenzie was allowed to transition into an endgame, and the extra pawn and better structure made it easy.

The second game is arguably less impressive. Grundy's 11th move was a bad one, as the Queen was very vulnerable on e2. This was compounded when he missed the double attack nature of Mackenzie's ...Qb6, which won a pawn in conjunction with his Knight hitting f4. When Grundy gave up a second pawn before trading Queens, the game was effectively over, even though it took a while to get there. These games are very, very uninteresting, hence why I'm speeding right through them.

Conclusion

At last, the Fifth American Chess Congress is over, and what a ride. This should have been the most interesting congress yet, featuring a race for first that came down to the very last round. But between bad games, the potential for foul play, and even more bad games, I can't say I was too satisfied looking through this. On the bright side, the next ACC wouldn't be held until 1889, though I can't say I'm looking forward to that either (but that is an issue for much, much later me to deal with).

As for Mackenzie, this is the last prominent American tournament he'll be featured in. He would play (and win) a match against Judd in 1881, but after that, it would be nothing but European tournaments for the Best in the West. He'll be making a big impact in his next tournament, and so I hope you look forward to it as much as I am.