The Steinitz Gambit and the Romantic Era Grandmaster Draw

While I was doing the research for my recent blog posts on the great tournament of London 1883 (check out part 1 and part 2) I came across the following game that I find very interesting.

Now, obviously the moves themselves aren't the most interesting, as is often the case with short draws. However, there are still a few points of intrigue. For one, what the heck is Polish master Szymon Winawer doing playing such a wacky opening? There's also the matter of a dispute started by the British Master Joseph Henry Blackburne. He accused the two players of colluding to make a short draw, when one of the rules in the tournament book explicitly states that all players must make a sincere effort in each of their games. This complaint was ultimately rejected, though the reason may come as a surprise to you.

However, rather than get into the discussion right away, I figure it would first be fun to take a more in-depth look at this opening, see its history, and try to wrap our heads around

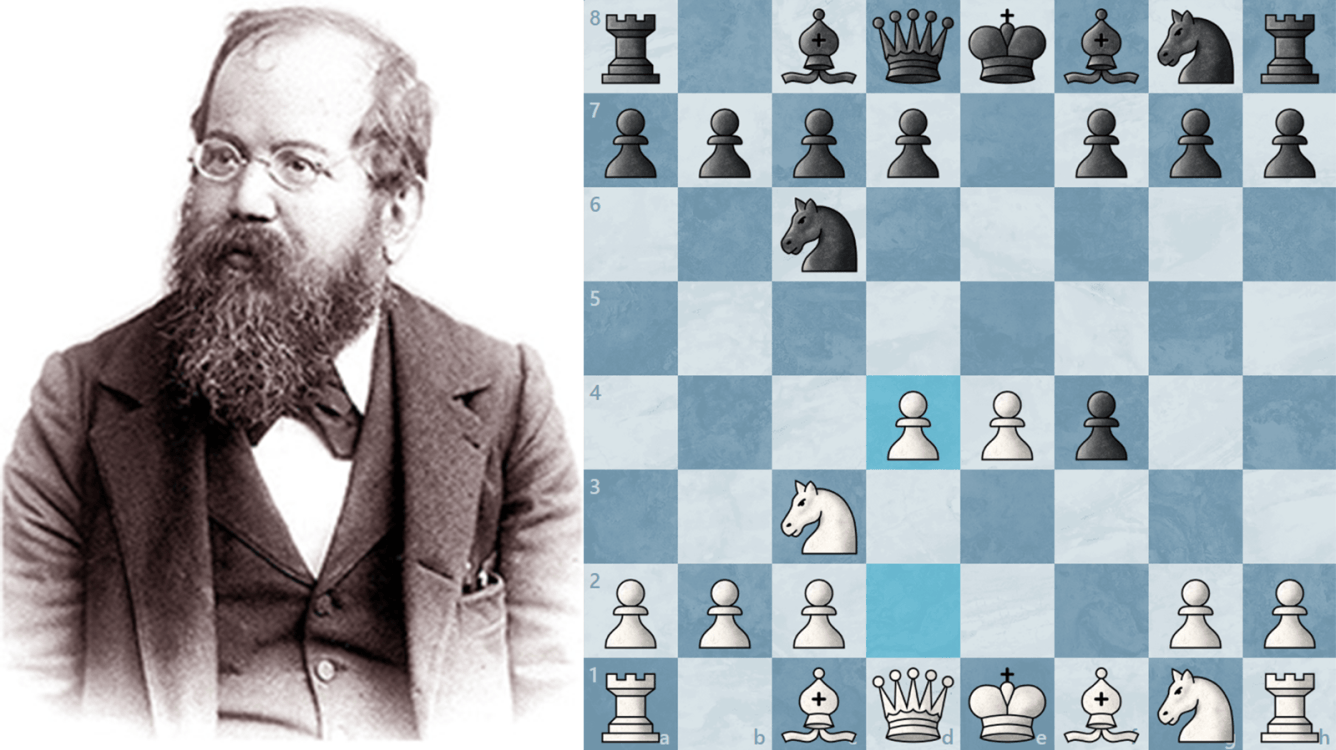

The Steinitz Gambit

1. e4 e5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. f4 exf4 4. d4

At first glance, this opening seems incredibly strange. Its similarities to the King's Gambit should be obvious, and d2-d4 isn't the normal move there, so what's the deal with playing it here? Let's ask Steinitz himself, who briefly commented on the opening in his notes for the aforementioned London 1883 tournament:

"The main object of this gambit is to make the [King] available for both wings in the ending. There is hardly any real danger for White in the present position, and he ought to obtain some advantage in consequence of his [King] being in the centre, if he succeeds in exchanging Queens, as was the case on the first occasion, when this gambit was adopted by Steinitz against Neumann in the Dundee Tournament of 1867."

A gambit that seeks to trade Queens and play a better endgame? It sounds insane, though the first few moves actually seem to support this conclusion. I figure there's no better place to start our exploration of this opening than with its debut, as mentioned by Steinitz, back in 1867.

Here Neumann's contribution to the theory is 5... d6, which is principled as a White Bishop quickly comes to f4. Steinitz's ideas are defended dogmatically, as his King is used as a supporting piece and his central pawns are protected at all costs. While Neumann was able to apply some pressure to the enemy King, as soon as the Queens were traded, Steinitz was proven correct: the position was much more pleasant for White, and the efficiency with which he accumulated an advantage and converted it was of the highest order.

The next tournament to really put this opening to the text was the Baden Baden 1870 event, where Steinitz employed the opening three times. Frustratingly, the theory advancement happens in reverse chronological order, so I'll be showing the games in reverse as well.

Against the French representative Samuel Rosenthal, Steinitz switched up his 8th move to one that won the exchange by force, doing the exact opposite thing that gambits tend to do. This particular game adds little to the theory, as Rosenthal tried a Knight sacrifice on move 12 that quickly showed itself to be unsound.

It was the game against German #2 Louis Paulsen that earned 5... d6 the "Paulsen Defense" appellation.

Paulsen introduced the move 7... O-O-O, which I believe to be the most fundamentally correct. What's less fundamentally correct, however, was 5 of Paulsen's next 7 moves being with the Queen, none of which posing more than single-move threats. Steinitz took this time to set up his forces, and by the time he "castled" by returning his King to g1, he had an extremely pleasant opposite-side castling game. The attack was ruthless.

After this tournament, the use of 5... d6 dropped off sharply, with its next top-level appearance also being at London 1883 (we'll get to that in a bit). One big reason for that was likely due to a game played before either of these two, in Steinitz's game against a local player Johannes Minckwitz.

Minckwitz introduced the idea of developing the Queen's Bishop by 5...b6 and 6...Ba6, which poses very practical problems for White along the other diagonal. The opening itself didn't inspire too much confidence, as while Minckwitz won a pawn, Steinitz had more than enough compensation in the form of strong central pawns and the Bishop pair. I believe it's purely the result that gave this opening influence, and it didn't happen in the manner you likely expect.

This particular variation would be popular among the American players Steinitz encountered after visiting the USA in 1882-83. Notably, the Cuban-American player Dion Martinez would essay 5... b6 against Steinitz no less than five times. However, the variation we're going to concern ourselves with would first be tried against Steinitz at the strong tournament of London 1872, by none other than his future rival, Johannes Zukertort.

Zukertort's Defense begins with 5... d5, which is the most forcing continuation as the pawn must be taken (I encourage the curious reader to boot up the position and explore it yourselves). This move effectively wins a tempo, and allows the attack on White's King to be leagues stronger. This particular game saw Zukertort sacrifice a Knight to open up the maximum number of lines, which forced Steinitz to run his King desperately over to the Queenside in order to survive. While Zukertort was unable to properly calculate his attack, and Steinitz kept his extra piece into the endgame, it's clear that players were slowly starting to figure out how to beat this opening (although I'm sure all Steinitz saw was one principled victory after another).

To properly show why this variation is an improvement over Paulsen's Defense, I'd like to show you what happened when somebody decidedly not Steinitz-calibur tried this same opening against the British-American master George Henry Mackenzie at the Third American Chess Congress (Chicago 1874):

We must then take a very long time skip, as the theory would not be advanced for about a decade. Steinitz only played in a handful of events (Vienna 1873 and 1882, and a match against Blackburne in 1876) and in none of them did he essay his gambit. He did play it quite a few times in less important games, though the vast majority of these games were in the 5... b6 line. The next time this opening would be tested would be in early 1883, when Steinitz played a six-game match against Mackenzie in New York.

In Mackenzie's first game with Black, he revealed the newest idea in the Zukertort Defense, 6... Qe7+. There are two possible responses to this move, and for this first game, Steinitz chose incorrectly. His choice of 7. Kf3 allowed for Mackenzie to develop his Knight especially favourably to f6, forcing Steinitz to waste a move on h2-h3 and preventing him from gaining the Black Queen's Knight. While Mackenzie made a few inaccuracies that allowed Steinitz to equalize (and eventually win), he had come one move closer to cracking this gambit right out of the opening.

The opening would be played again in the sixth and final game, with the opening's true purpose being revealed: drawing by perpetual check. In context, this makes perfect sense: Steinitz had already won the match 3.5-1.5, and this game had no real stakes attached, so they might as well just get it over with and move onto the next thing.

Only a few months later, the London 1883 tournament would take place. Steinitz would have White in each of its first three rounds, and the Steinitz Gambit was played in each one of them. Let's take a look at the games, as they'll provide serious context for something mentioned at the start of the chapter.

Round 1: vs. Szymon Winawer

We're starting with the guy who played the quick draw at the start of the post, yep. This game doesn't contain much theoretical importance due to Winawer playing 5... d6, but it does reinforce why Zukertort's Defense is the way to go. Winawer really only played one inaccuracy on move 10, but that's all Steinitz needed to take over the game. Once the Queens were traded and Steinitz collected an exchange, the result was never really in doubt.

Round 2: vs. Berthold Englisch

You give Englisch a way to draw, and that man will readily take it (that's mostly a joke, but Englisch did have one of the highest draw rates among his peers). Steinitz improved upon his Mackenzie games with 7. Kf2, though as you can see, the resulting position is very uncomfortable for White. While Steinitz writes about how bad his 10th move is, the mistake doesn't actually come until move 14, though Steinitz would have had to accept trading Queens in a position where he's down two pawns. His move made it three.

Round 3: vs. Mikhail Chigorin

Prior to their 1889 match, Chigorin managed an impressive 3-1 score against Steinitz in tournaments, including this game. This came despite Steinitz playing his preferred 10th move, which left him with only a one-pawn deficit and at least a little shelter for his King. Now, it's worth mentioning that this game was actually lost in the middlegame, with Steinitz miscalculating the position after his (correct) exchange sacrifice. However, the point stands that he was never really better, which is definitely worthy of a strike against the opening.

After this game, Steinitz would not play the opening again in this tournament.

The game shown at the start of the chapter, Winawer-Rosenthal, was played in round 4, only two days after Steinitz's loss to Chigorin. These two losses formed the basis for the committee's decision to ultimately reject Blackburne's complaints about potential match fixing. The Steinitz Gambit had been shown to be a very deadly weapon in the hands of the right practitioner (as evidenced at the start of this tournament even), but now Black had found a line where White either accepts the perpetual check or plays a very difficult game; you can't possibly punish the players for this sort of outcome. Thus, nothing was done (though neither player placed that high so not much would've changed either way).

I hope you enjoyed this look at the Steinitz Gambit, but hopefully not enough to inspire you to play it in your own games. To cap off this post, I'll leave you with one last game; given that it capped off a very important match, I think it's a perfect fit.