Warrior at the Chess Board

About a decade ago, WilhelmThe2nd, from Chessgames.com sent me this article by Fedor Bohatirchuk about his personal memories of Efim Bogoljubov. The article, which had no accompanying pictures, is given below with some elaboration by me in red.

It should be noted that both Bohatirchuk and Bogoljubov are somewhat controversial due to the untenable situation in which each found himself during WWII.

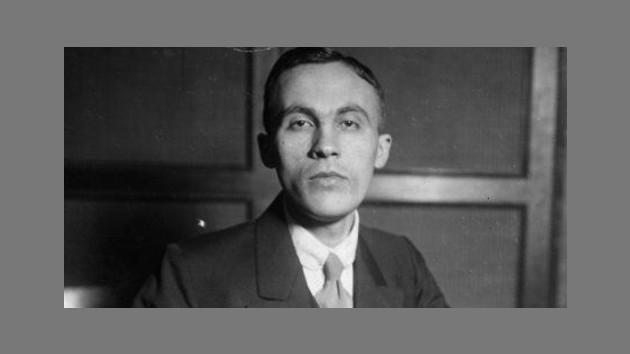

Fedor Bohatirchuk (on the left) and his friend and fellow Ukrainian,

Efim Bogoljubov (on the right) in 1912, from "Шахматы" № 1, 1926.

I became acquainted with Efim Dmitrievich in Kiev's chess club, where I came one evening of te winter of 1908. I was then 16 year old, a gymnasiast (i.e. a student in a preparatory school); he wore the uniform of a local seminary (theological school). The students of this school never visited the chess club and therefore the newcomer attracted the attention of everybody. But there was another reason for much attention — the young seminarist demonstrated an extraordinary chess skill, defeating easily all the best players of the club. It was unusual in the club, but Bogoliubov was at once given the first category and he entered the handicap tournament which started this evening in this capacity. I was a weaker player and participated in the same tournament as 5th category.

In this first tournament in his life, Bogoliubov finished second (first went to Kiev's champion (B. Isbinsky [probably Stefan Konstantinovich Izbinski who died in 1912]). After this debut Bogoliubov very quickly rated among Kiev's best players. It was not so easy because at this time many good players resided in Kiev permanently. Besides the above mentioned B. Isbinsky, who died early, such masters as Lowisky [Moishe Lowtzky], Dus-Chotimirsky, B. Berstein [probably Ossip Bersntein] visited the chess club or a cafe every evening.

I remember how seriously Bogoliubov had taken up chess. It was more than a hobby for him, he dreamed of being a chess champion. We laughed at him, we could not understand his desire to become a chess professional; but he did not pay any attention to our jokes and stubbornly continued his chess studies. I remember that even at this time he surprised his adversaries with extraordinary knowledge of chess openings; the famous Bogoliubov's "trunk if variations" was a real threat to all his opponents.

In 1909 Bogoliubov took part in the St. Petersburg preliminary tournament in which young Alekhine placed first. Though Bogoliubov in this tournament demonstrated also his extraordinary chess talent, he himself was quite unsatisfied with his results — he simply did not understand how it could happen that he did not take first place in such a "weak" tournament. Even at this time the self-confidence of Bogoliubov was the topic of our jokes. But he was never angry with us and liked to say: ""He who laughs last, laughs best." It was really difficult to believe then that this theological student would become one of the best players in the world.

In 1910 E. Bogoliubov entered a Warsaw polytechnical high school but was obligated to quit it very seen because chess left him too little time for studies in polytechnics.

In 1914 many Russian players, including Alekhine, Bogoliubov, Romanovsky, Rabinovich and others (me too), were sent to represent the Russian chess art at the Mannheim International Tournaments. Alekhine and Bogoliubov, having the title of chess master, entered the international tournaments. In this extraordinarily strong tournament Bogoliubov did not play so well as it was expected, maybe the unusual European surroundings distracted his attention from play.

After the war broke out (World War I), all the Russian players but three (Alekhine, Saburov and I) were interned in South Germany for a period of the whole year. Bogoliubov married a German lady and very soon became the happy father of two charming girls. At the end of the war all the Russian players returned home but Bogoliubov, who remained with his family (and A. Selezniev also remained).

Until 1924 I heard little about Bogoliubov; it was the time of military communism and we had in mind rather the bread and potatoes but not chess. Scarce communications from abroad informed us about the progress in Bogoliubov's chess career.

After a new economical policy (NEP) was proclaimed by Lenin, life became a little easier, and we again began to play chess. In 1924 Bogoliubov and [Alexey Sergeyevich] Selezniev accepted invitations to the All-Russian Championship.

We expected to meet a shabby chess professional, but we were surprised to come across instead a modern European, dressed as a London dandy, smoking occasionally a very expensive cigar. Such a metamorphosis of our friend seemed to be a fairy tale! And how wonderfully he played chess! He took first prize with the utmost ease, having lost no games.

He was a real superior class if chess player, unknown to us. As in the times at Kiev, the knowledge i chess openings was the strongest weapon in the hands of Bogoliubov. Next year Bogoliubov won easily a match with P. Romanovsky. But his real triumph was his in the 1st Moscow International Tournament in 1925. He finished first, before Capablanca (then in the zenith of his fame) and Lasker. His deep and brilliant play made us proud of our chess champion.

After this victory Bogoliubov challenged Capablanca but the challenge was not accepted. It is not the aim of this article to analyze thoroughly the chess treasury left by Bogoliubov — every chess player knows his achievements. Even Alekhine was very close to losing his chess crown to this theological student in their first match. At any case, he did not prove this superiority over Bogoliubov so easily as was done by him at this time in his encounter with other players.

In 1926 Bogoliubov refused to come back to the Soviet Union and was divested of Soviet citizenship. Very soon afterwards the iron curtain divided us from the West. It was dangerous to correspond with everybody in foreign countries. especially with such an "enemy of the people" as Bogoliubov. Therefore, I lost any connection with him.

Only in 1943, after my flight from Kiev, did I come across him in Cracow and later in the Radom tournament. This time he had an official position in the German army in the capacity of chess instructor. I was told by one of my friends that Bogoliubov wore his Nazi badge only in case it would be necessary to buy a railway ticket or something in a store forbidden to common mortals.

Truly, it was necessary only to have a short conversation with in order to know that he was in the party only with the aim of disguising himself and saving his daughters from mobilization. He told me how difficult it was, even with a Nazi membership in his pocket. So fat as I know, Bogoliubov never accepted Nazi ideology, was anti-Hitler, and never approved of the cruel practices of this madman.

I remember that at the time of the Radom tournament, he succeeded in getting good radio reception. After the round, we sat around it the whole evening and listened to the information from neutral stations. I never suspected before the the military situation of Nazi Germany was so bad. Bogoliubov laughed at my naive surprise and said the end of Hitler was very near.

Another time he told me about an event one yer before when he wore his Nazi badge during a simultaneous display in one of the military hospitals. Suddenly one wounded soldier hit him on the badge and broke it. After this incident he never wore the badge during chess games but demonstrated it to his friends.

After the Allied victory I did not hear about Bogoliubov for two years. Later on, I learned he ad some difficulties in clearing himself in a denazification board. Finally he was screened and allowed chess activity. I was very glad because I knew very well how far Bogoliubov had been from any political activity, especially of the side of Hitler.

Bogoliubov was very greatly offended by the refusal of FIDE (this time dominated by the Soviet delegation) to recognize him as a grandmaster and to allow him to participate in international tournaments (a decision that was only canceled in 1951).

In vain I tried to explain the obvious reasons for this decision —such injustice he could not accept. "Ask everyone in Germany- let anyone prove my adherence to the Nazi for other than formal reasons, and I will obey, but now it is clear that the only reason is the revenge of the Soviets." This refusal hurt him financially because it took away one of his sources of his earnings.

The last time I met the later Bogoliubov was at a small international tournament in Kassel in 1947. He finished first. But his health had already deteriorated. It was clear he was in need of serious treatment. But his financial situation was very bad; he had to support his family—and consequently he worked, playing, playing and playing. I imagine how he longed to be over with his play every day, every hour. But he always kept his humor and took it all very easy.

Now the sad news about his death. . . Looking back into the life of this former theological student, I consider that maybe he was right to choose the life of a warrior at the chess board. Here, at this board, he had everything a life might give, as Henry sometimes said, war, victory, fame and love. To us —chess players— he left the wonderful games, which must be studied, and which will become part of the world of chess history.

The author, Dr. Feodor Bohatirchuk, is a distinguished Ukrainian specialist, noted for research work on cancer. Now residing in Ottawa, Canada, Dr. Bohatirchuk possesses a noted reputation as a chess layer. Many times Champion of Kiev and the Ukraine, he tied for thid with Dus-Chotimirsky in the II Russian Championship of 1923, tied with Lowenfisch for third in the III Russian Championship of 1924; placed 11th — but ahead of Rubenstein and Spielmann in the 1st International Tournament at Moscow in 1925; tied for first with Romanowsky in the V Russian Championship of 1927 — ahead of Botvinnik; tied for third with [Vladmir] Alatorzev and [Boris] Werlinski in the VII Russian Championship in 1931, and tied for third with [Nikolai Nikolaevich] Riumin in the IX Russian Championship in 1934. He is one of the few players with a plus score against Botvinnik — three wins and one draw in four tournament encounters - The Editor.