The First Computer Chess Championship in the USA

For nearly 20 years computers have dominated chess. These advanced devises not only defeat the best players, but have become indispensable as training tools, analyzing partners and always-ready opponents.

Of course computers weren't always so universal and chess programs weren't always so strong. A precise history of the development of computer chess is hampered by the fact that much of that development wasn't organized or even documented but performed by talented amateurs and hobbyists who loosely shared their knowledge. But certain landmark events highlighted the state of that development in specific points in time. One of these events was the first computer chess championship in the U.S. which was played between Aug. 31 and Sept. 2, 1970 in the Hilton Hotel in New York City.

The First Computer Chess Championship came about in a rather serendipitous fashion. Every year the ACM (Association for Computer Machinery) held a conference. The ACM is the largest organization for computer professionals. During their conferences they usually had a form of computer-oriented entertainment. The task of devising or procuring that entertainment fell on Kenneth M. King, director of the Columbia University Computer Center and Monroe Newborn, associate professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Columbia who were joint chairmen of the Special Events committee for the ACM conference.

According to Mr. Newborn the idea for this championship came about when Dr. T. Anthony Marsland, who had recently earned his doctorate in electrical engineering and was working as a research scientist at the AT&T Bell Labs in New Jersey, wrote the committee offering to bring his computer program to the conference and demonstrate its play against a person or even another computer. This idea suggested a more ambitious one of bringing all the known computer chess programs in the United States together for a contest to see which one was best - and perhaps why.

Six developers responded to the invitations and took part in the contest. Probably one of the major disappointments was the refusal of the most famous chess program of that time Mac Hack (Mac Hac/MacHack/Mack Hack/MacHac - they never settled on a spelling), to participate. Mac Hack Six was written by Richard Greenblatt at MIT in the mid-sixties. As part of a study on A.I., Mac Hack only played human opponents (and actually played in some USCF tournaments. According to Bill Wall, "By 1969, MacHack played in 18 chess tournaments and had played over 100 completed games." Greenblatt seems to fear that entering a computer only tournament would somehow compromise the A.I. aspect. Greenblatt did, however, consider his program among the best. Mac Hack was run on a PDP-10, a mainframe computer built by the Digital Equipment Corp.

The image above shows the 6 entries and the results.

Monty Newborn, Sam Matsa (pres. of the ACM), David Slate, Larry Atkins and

Monty Newborn, Sam Matsa (pres. of the ACM), David Slate, Larry Atkins and

Ben Mittman (director of the Vogelback Computer Center at Northwestern U.)

1971

The winner was Chess 3.0. This program was originally called simply "Chess" when it was developed by 2 undergraduate students, Keith Gorlen and Larry Atkin along with a post-graduate student, David Slate from Northwestern University (in Evanston, Ill.) in 1968. In 1970, the program, then called "Chess 2.0," was being tested by IM David Levy in England and using his suggestions, the program was improved and called "Chess 3.0." This is the version that competed in the ACM Computer Chess Championship in 1970. It was run on a CDC 6400, a mainframe computer built by Control Data Corporation.

Chris Daly with his Daly CP installed on IDIIOM

Chris Daly with his Daly CP installed on IDIIOM

(The cover photograph also displays an IDIIOM)

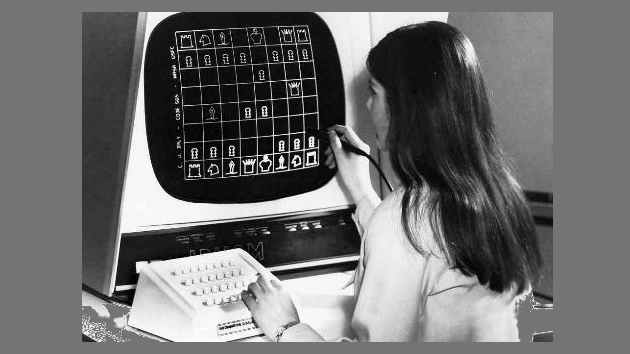

Second place was captured by Daly CP. Chris Daly was a researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center at Goddard Maryland. IDIIOM, an acronym for Information Display Inc. Input-Output Machine (Information Display Inc. was formerly RMS Associates, founded by Carl Machover, Ken King and Al Vollendweider at Vernon, N.Y. in 1960), was the first integrated —a workstation coming with a program, a processor and a display— and the first affordable CAD platform on the market. Daly wrote his chess program specifically for IDIIOM which, as the photo above shows, was a graphical interface that incorporated a light pen for selecting the piece and the destination square.

The IDIIOM was connected to a Varian 620/I with 4K of memory. The Varian minicomputer was a product of Varian Associates out of Palo Alto, California.

Tied for third were J. Biit and COKO III. J. Biit, written by the world correspondence chess champion, Hans Berliner, was a favorite to win. J. Biit was another acronym that stood for "Just Because it is there." Berliner, inspired by Greenblatt's MacHac, began working on his program while employed by IBM in 1968 and continued at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh as a doctoral student at the Dept. of Computer Science . Since he was at CMU, J. Biit was, of course, designed to operate on their Digital Equipment DEC PDP-10 mainframe computer. At the time of the tournament, use of the computer was unavailable to Berliner so Kenneth M. King offered him use of Columbia University's more advanced IBM 360/65 which was supposed to be compatible to the DEC PDP-10 but turned out to be less compatible than first assumed. Berliner, along with 4 assistants (future chess programmers Steve Bellovin, Aron Eisenpress, Andrew Koenig and Benjamin Yalow) spent 2 weeks hurrying to fix the incompatibility issues. Berliner's program was a bit different from the others as it searched a very limited tree but did so far more deeply.

COKO III was developed by Dennis Cooper and Ed Kozdrowicki (hence the name COoper+KOzdrowicki). Kozdrowicki was a professor in the Dept. of Electrical Engineering at the University of California and Dennis Cooper was a student. At the time of the tournament, Cooper was working at Bell Labs in New Jersey, but still collaborating with Kozdrowicki. One of the advantages of COKO III was that it could by run on a large number of computers. However, since it was programmed to give top priority to tactical elements which also limited it's search particularly in endgames, it had some serious weakness too. During this competition, COKO III operated on an IBM 360/65 mainframe located at the Bell Telephone Labs in Whippany, N.J.

IBM 360/65

IBM 360/65

Schach was written by Rolf Smith for his Masters in Computer Science at Texas A&M along with fellow grad student Franklin Ceruti and Dr. Dan Drew, Texas A&M professor and director of Computer and Information Science. Schach also ran on an IBM 360/65 mainframe but was a comparative memory hog requiring a minimum of 72K. Schach experienced a lot of technical difficulties during the experiment despite having Dr. Drew and grad students James Roberts and Elliott Bray manning the IBM in Texas while Prof. Udo Pooch, Ceruti and Smith worked from the tournament headquarters in New York.

Tony Marsland's program Wita or the Marshland CP came in last place. Originally from England, Marsland received his PhD in Electrical Engineering from the University of Washington after which he went to work briefly for Bell Labs in New Jersey. He moved to Canada becoming joining the faculty of the Computer Science Dept. at the University of Alberta. He wrote Wita (later called Awit, the name came from from a Dark Age English institution called Witenagemot or Witan [the members], meaning "meeting of wise men') while in Washington but during the championship tournament his program ran on the U. of Alberta's Burroughs 5500 mainframe computer.

Below is Hans Berliner's article on the championship from "Chess Life and Review," Nov. 1971.

In New York City from August 31 to September 2, 1970, six chess programs running on computers as far away as Texas and Alberta, Canada, competed for the title of U.S. Computer Champion. The tourney was a three-round Swiss-system event, the time limit being 40 moves in two hours, with up to three 20-minute breaks allowed each computer in each game for equipment difficulties.

Three of the computers were directly connected by telephone lines to input/ output terminals in the New York Hilton Hotel. Here the operators of the programs typed in the moves made by the opponent computer, and in due time the computer would type back its reply. Two other computers were connected by voice telephone so that the operator at the computer site merely had to say the move made by the computer into the telephone for it to be actually played in New York. The sixth competitor was a mini-computer, so called because of its size and cost. This computer was located at the tournament site and had a television-type display on which the current position was shown. When the computer made a move the display changed. When its opponent made a move, this was communicated to the computer by means of a "light pen" with which the operator touched the piece that is moving and then the square to which it is going.

The tournament resulted in a well-deserved win for a Control-Data Corporation 6400 computer, a large Scientic machine programmed by and located at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. This program beat all of its opponents to score 3-0.

Second place was taken by the mini-computer, a Varian 6201 belonging to Information Displays, Inc. This program scored 2-1 but benefited greatly in the pairings by getting to play the two weakest programs and only one of the better ones.

Tied for third and fourth with 1½-1½ were a program developed by Dennis Cooper of Bell Telephone Labs in New Jersey and a program developed at Carnegie-Mellon University by Hans Berliner, the world correspondence champion. The latter program ran on an IBM 360/91 at Columbia University. Fifth was a program developed by a team at Texas A&M University which scored 1-2, and last with 0-3 was a program developed by Tony Marsland and running from the University of Alberta in Canada.

There were audiences of up to 400 persons, including Grandmaster Pal Benko. Major feature space was given the event in The New York Times. Frequently the audience was derisive of a move made by one of the computers, little realizing that the obvious move preferred by the audience was inferior. It is fair to say that no new chess theory will develop from this tournament, nor were any extremely brilliant or profound moves made. However, the tourney also shows that since 1967, when the first real breakthroughs in computer chess were made, quite a bit has been accomplished. The winning program played a very steady game at about the Class B level. It appeared to be totally free of gross blunders and would probably hold its own in an average chess tourney. It was too bad, in a way, that the first American program to play worthwhile chess did not compete. This program was developed by Richard Greenblatt of M. I. T. and has been improved over the years. It is rumored to be able to play Class A chess at present. It would have been interesting to see it compete with the Northwestern program.

The problems of programming a computer to play chess are rather imposing. Clearly the computer cannot look at all possible game continuations up to checkmate (or a draw) as there are 10120 possible games from the initial position. If every atom in the universe was a computer and each had been calculating chess variations at the rate of one per second for 14 billion years (since the beginning of the universe), they would have completed only a small fraction of the total number of variations to be calculated. Similarly, there are about 10120 legal chess positions. If we could store the best move for each one of these positions, then we could have a computer that played perfect chess. But there are no storage devices to hold so much information nor people to catalog so many positions, not to speak of the search time required by a computer to find the right position in its catalog. Chess playing computers, therefore, must work very much as you and I, analyzing plausible-looking alternatives and eventually making judgments about the qualities of a given position. The variations analyzed are then arranged as a "tree of possibilities" and the values assigned to positions at the end of "branches" are compared to find the computer "idea" of best play for both sides. The computer then makes the first move of this best play sequence.

Presented below is a game from the computer championship. When Black made its 47th move, the audience burst into applause.

.

The rules were established by Monroe Newborn, Keith Gorlen, Dennis Cooper and Tony Marsland during a meeting several weeks before the tournament and printed in the brochure as below:

According to Newborn in "Computer Chess" :

The three-round Swiss-system tournament was held in the Rhinelander Room in the New York Hilton Hotel on the evenings of August 31 to September 2. Computers were connected to the Rhinelander Room via telephones from Illinois, Texas, New Jersey and two New York Locations; the IDIIOM system was at the site of the tournament. At 5:30 each evening the games were scheduled to begin, but more typically they began around 6 P.M. It was a rare event throughout the tournament when all three games were simultaneously in progress. Almost always at least one computer was having difficulties. However, in general, the better programs were more reliable, and in turn the better games had fewer interruptions. Each evening there were several hundred spectators in attendance, including computer specialists and chess experts. The most notable chess experts were Pal Benko one of the top players int eh United States, who seemed somewhat unsure of the future potential of computers in the chess world, and Al Horowitz former chess editor of the New York Times, a long-time skeptic regarding their potential.

Throughout the tournament there was a most casual and informal atmosphere in the Rhinelander Room. Good moves were met with cheers from the audience; bad moved were hissed. The programmers discussed moves they expected their computers to make,reporters interviewed the participants, and Berliner ate his sandwiches. Berliner, an old pro of the human chess tournament circuit, came well stocked with food each evening.

It must be remembered that MacHack, considered possibly the strongest computer at that time and the only one with a USCF rating was only rated at 1529 Elo. The games, as Berliner reminisced, broke no new theoretical ground, and could generally be considered mediocre. Still, it's all about perspective.

(All 9 games- 8 below and 1 in the Berliner article above -are given here.)

Chess Computer Loses Game in a King‐Size Blunder

By JOHN C. DEVLIN

The world's first major chess tournament played by computers proved yesterday that masters have little to fear from machines and that not even a million‐dollar electronic marvel is blunder proof.

In fact, the computers, in their shortcomings,‐ were almost human.

The computer contestants were based in Texas, Illinois, New Jersey and New York, with the tournament operating out of a control center on the third floor of the New York Hilton Hotel. The tournament was directed by Prof. Monroe Newborn of the department of electrical engineering and computer science at Columbia University.

Professor Newborn originated the plans for the tournament, which opened Mon day night and is expected to end tonight.

Last night the play drew nearly 300 spectators, who watched in more‐or‐less appreciative silence as the computers’ moves were transferred to large posterlike chessboards.

Technical Delay

Among those who have dropped by to watch have been international grandmaster Pal Benko and Al Horowitz, chess editor of The New York Times.

Six teams are competing, with three games going on simultaneously.

The first game — which began 45 minutes late because of technical difficulties in getting the equipment installed and hooked up — was won by a $7‐million Columbia University computer programed by Hans Berliner, the national postal chess champion.

Its opponent was a computer programed by Tony Marsland of the computing science department of the University of Alberta, Canada. The Canadian computer lost when, on its ninth move, the Columbia computer, playing Black, attacked the White king and queen simultaneously.

As in ordinary people tournaments, each side was permitted a maximum of 40 moves in two hours of play. But the Columbia machine used only 12 minutes for its winning game; the loser took 20 minutes.

Mr. Berliner, who is studying at the Carnegie‐Mellon University Computer Center in Pittsburgh, said he had spent “two years, on and off,” programing chess strategy into the computer.

The computers need human help during play. A move made here is relayed by telephone line to the opposing computer. The received move is fed into the opposing com puter by a human. The computer then “thinks” out its move and sends it by phone to New York, where again human feeds the response into the computer.

In Game No. 2 the winning computer was programed by Keith Gorlan, representing a group from Northwestern University, in Evanston, Ill., playing against a computer programed by Dennis Cooper of the Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc., Whippany, N. J.

In Game No. 3 a computer programed by Chris Daley of the Goddard Space Flight Center, Goddard, Md., beat one programed by a group with a computer at Texas A. & M. University, College Station, Tex., headed by Franklin Ceruti and Rolf Smith, both Air Force captains.

Programmers’ Hobby

Professor Newborn said that on the average a computer took one to three minutes to analyze a situation and make its move.

The cost of programing the computers was almost negligible because the programers did it mainly as a hobby. The chore took about two years.

As for the scientific value of the computer chess com petitions, the professor said:

“There has been this fundamental question as to whether computers can think. To a limited degree this competition shows how well a computer can cope with a complicated question.”

By chance the tournament fell on the 200th anniversary of the appearance of the world's first chess automaton, called The Turk. Introduced in the Royal Palace in Vienna by its inventor, Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen, it defeated almost all corners — including Napoleon —and baffled some of the best minds in Europe.

The automaton was the figure of a Turk seated at a cabinet on which was a chess board. Actually the Turk was operated by a man hidden by an ingenious set of false panels.

A Computer's Limitations

Some modern chess players have been known, upon losing, to weep, sweep the pieces from the board or even smash the board in fury. Mr. Horowitz remarked: “That's something the computers can't do.”

Mr. Horowitz also analyzed the game between the Columbia and Alberta computers. He said:

“White's first move establishes the opening as the English, and the opening is orthodox until White's third move. The deployment of White's queen with 3.Q‐Q3 reflects strategy of control of the center, programed into the machine, though there are better ways of achieving this goal.

“Theoretically, Black goes astray on his sixth turn. He could gain a pawn with 6 … QxP, but on his eighth turn, White blunders by bringing out his king, making it a target, and by walking into what is known as a pin, which cost a piece.”

Had a man played White's ninth move, he said, it would have been called a “finger fehler”—a slip of the fingers —but since a computer has no fingers it will have to go down as an electronic blunder. As its next move the computer resigned.

The score of that game follows:.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

As can be seen, the computers and the programs were still in their early competitive stages. But this tournament seems to have been a sort of watershed event that accelerated greater developments. If nothing else, it laid the groundwork for the 23 ACM tournaments that followed. These tournaments featured such well known programs as Belle, ChipTest, Cray Blitz and Deep Thought.

.

.