Stalemate Your Opponent!

For many readers, the title of this article might look weird. The possibility of stalemating your opponent usually means that you are in charge of the game. If you are in the driver's seat, why would you settle for a draw? Moreover, just earlier this year I warned less-experienced players that when you have a huge material advantage against your opponent's lonely king, the biggest danger for you is a stalemate. So, what's going on here? Well, let me explain.

When we talk about a stalemate in chess we can mean two absolutely different things. One is the real stalemate, where a player has absolutely no legal moves on their turn and the game ends in a draw. It is obviously a bad thing when you have a winning position and stalemate your opponent for real. This is what happens in numerous games of less experienced players, like the following:

Even if Black blundered his queen instead of playing the unfortunate 56...f5??, they would have had a winning position. But a stalemate is the worst that can happen to you in a position like this, which is exactly what I was talking about in the above-mentioned article.

But there is another meaning for "stalemate" that you can frequently hear from strong players. When a grandmaster proudly says "I completely stalemated him" you can even feel some undertone of bragging. In this context, a stalemate means that the opponent could barely move and in reality, the situation on the board is close to a zugzwang.

Here is what GM Garry Kasparov wrote in his book Kasparov on Kasparov, Part I about his game against GM Svetozar Gligoric: "But then my opponent went wrong, and in the end I was able to stalemate his pieces." Here is the game, where Kasparov again mentions a stalemate in his annotations to Black's 33rd move:

So, using Kasparov's games as an example here is the kind of stalemate to avoid:

And here is a very desirable situation where your opponent's pieces are "stalemated" and therefore practically cannot move:

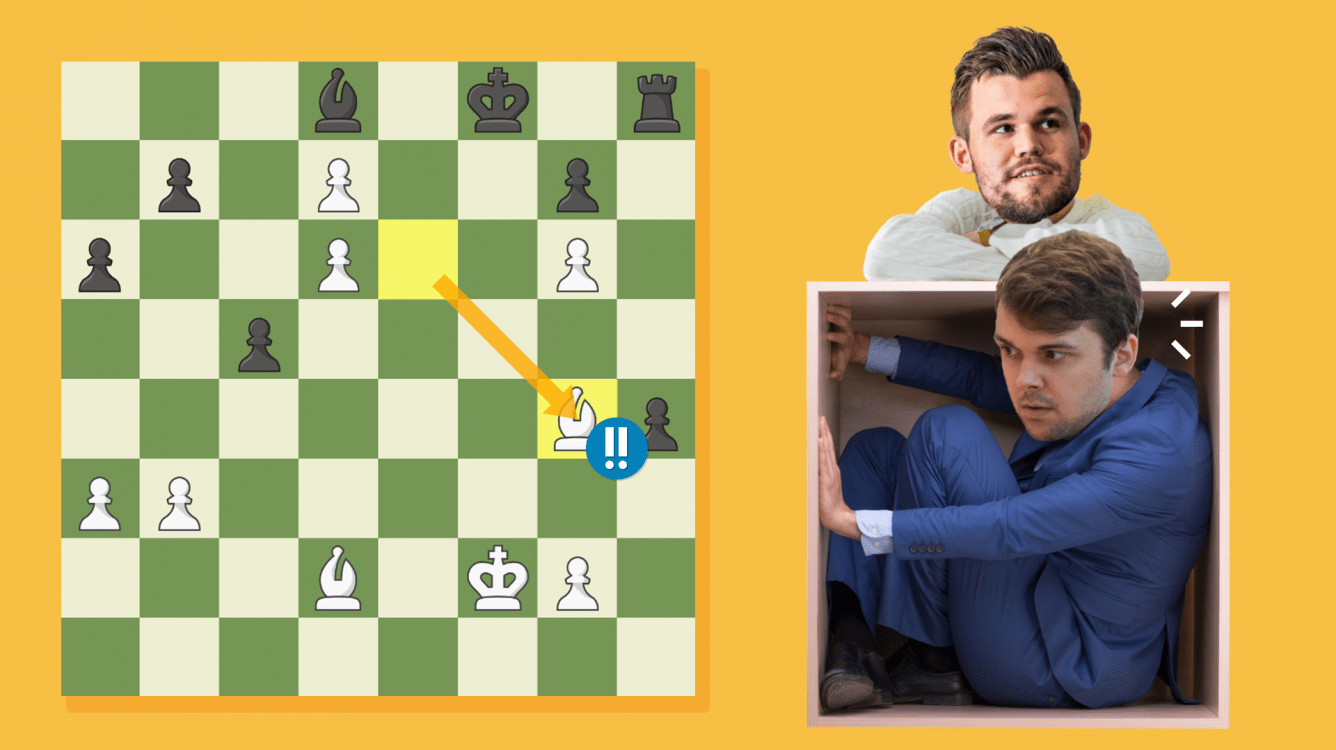

The recent 2021 FIDE World Cup is going to be remembered for many different things. What first comes to mind is GM Jan-Krzysztof Duda's triumph or how many participants withdrew during the event (and even in the middle of the game!) due to COVID-19. However, I will remember this tournament for two masterpieces produced by GM Magnus Carlsen. Each of them would be exactly what Kelly Clarkson meant by singing "Some people wait a lifetime for a moment like this."

The world champion produced these two gems back to back in consecutive days! It is especially impressive since his opponent, GM Vladimir Fedoseev, is an extremely strong and resourceful player. Yet, in both games, the Russian grandmaster's pieces reminded me of a person leaving a bar at the end of the night. He needs to get home, but somehow their legs are not moving. Unfortunately, there is no taxi or Uber on a chessboard, so Fedoseev's pieces kept sitting in the bar while their kingdom was burning.

Please notice Carlsen's moves 16 and 18. He sacrificed a pawn and then an exchange on the same f4-square. I liked it a lot! About two years ago I wrote an article "Magnus Carlsen's Unfinished Masterpiece" about his sacrifice on the same f4 square, so I am happy to see that the world champion has finally finished his masterpiece!

The second game of the match was equally impressive:

Games like these are incredibly rare and difficult to produce. Nevertheless, if you are up to the challenge, the first step would be to establish a habit of asking "what does my opponent want to do?" before you play your move.

For beginners, this question would be a good way to notice their opponent's hidden threat of a checkmate or to avoid hanging pieces. For more experienced players, this question can help them to play moves like Carlsen's 47. Bg4!, preventing Black's rook from getting back into the game through the h5-square. In many cases, it is little moves like this that are the building blocks of amazing masterpieces!

To summarize, avoid "bad" stalemates and instead stalemate your opponent's pieces, just like Carlsen did!