Lionel Kieseritzky

The ancient Estonian city of Tartu lies about 2500 miles from Paris, France. In the 19th century Tartu didn't exist as such but rather was known as Dorpat under the umbrella of the Imperial Russian empire. Dorpat lay in Livonia, a part of the Russian Empire that had formerly been under Polish rule, comprised loosely of the Baltic area now known as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

It's in this place that our story begins.

On the day before leaving his hometown of Dorpat for good under the weight of some unspecified scandal, the man with the improbable name of Lionel Adalbert Bagration Felix Kieseritzky, at the augural age of 33, put on a show. Although he was well known as a talented amateur pianist, the show he arranged was a chess show - a living chess game played out in the public gardens. And quite fitting it was since Kieseritsky was soon to become not just transplanted to Paris but transfigured from a teacher of Mathematics into a teacher of Chess.

Although Livonia had former Polish ties, Kieseritzky wasn't Polish but of Germanic blood. His father was a well-to-do Estate Manager. Lionel himself was socially active and practiced at putting on theatrical shows, generally more of a musical or dramatic variety. Entertainment coursed through his veins as did Chess. That he had been the best player in Livonia seems obvious as he had been playing correspondence chess with Carl Jaenisch and immediately upon arriving in Paris set up shop at the Café de la Régence teaching chess for 5 francs a game.

Testifying to Kierseritzky's chess reputation, George Walker, in 1838, wrote:

To whom is destined the marshal's baton when De la Bourdonnais throws it down, and what country will furnish his successor? The speculation is interesting. Will Gaul continue the dynasty by placing a fourth Frenchman on the throne of the world? -- the three last chess chiefs having been successively Philidor, Deschapelles, and De la Bourdonnais. I have my doubts. Boncourt is passing, St. Amant forsaking chess; and there is no third son of France worthy of being borne on the books, save as a petty officer. May we hope that the laurel is growing in England? No! Ten thousand reasons forbid the supposition. Germany, Holland, and Belgium, contain no likely man. At present De la Bourdonnais, like Alexander the Great, is without heir, and there is room to fear the empire may be divided eventually under a number of petty kings. M. Deschapelles considers that chess is an affair of the sun, and that the cold north can never produce a first-rate chess organization. I cannot admit the truth of the hypothesis; since we find the north, in our time, bringing forth the hardest thinkers of the day in every department. Calvi of Italy will go far in chess; but so will Szen of Poland, and Kiesaritzki of Livonia. The imperial name of the latter is alone a pawn in his favour; but, I repeat, the future is yet wrapped in darkness.

The only know image of Lionel Kieseritzky

By the mid 1840's Kieseritzky was probably the strongest player in Paris and possibly the world - though such a claim would undoubtedly be fodder for intense debate. While the everyday contests against weaker amateurs were his bread and butter, Kieseritzky played a good many matches against strong masters with generally good results -

1839 vs. St Amant 1-1=1

vs Rousseau - won a 100 game match

1840 vs. Boncourt - even score

1843 vs. Buckle at QB odds - Buckle won

1845 vs. Calvi +7-7=1

1846 vs. Horwitz 7-4=1

1846 Staunton played Harrwitz and Kieseritzky in a rather peculiar 2 game simultaneous triangular contest. Staunton gave Rook odds while his two opponents played blindfolded. Harrwitz won both his games; Kieseritzky lost both his games

1847 vs. Harrwitz 11-5=2

1848 vs.Buckle 2-3=3

1850 vs. Schulten 107-34=10

vs. James Thompson at P&move odds. Thompson won the majority.

1851 vs. Buckle 2-1

vs. Mayet 13-8=1

vs. Mayet 13-8=1

vs. Szen 13-7

vs. Loewnthal 9-8

vs. Bird 8-2

vs. Jaenisch 1-1=1

vs. Anderssen 9-5=2

vs. Mongredien 1-2

When Staunton was in Paris in Oct.-Nov.1844 trying to organize a third match with St. Amant - which he abandoned due to illness - he also tried to arrange one with Kieseritzky, but the match never materialized:

MATCH BETWEEN MR. STAUNTON AND M. KIESERITZKY.

Our readers will learn with pleasure that, whatever be the event of the match between Mr. Staunton and M. St. Amant, a match is being arranged in Paris between the celebrated Livonian player, M. Kieseritzky, and our English champion, to take place early in the coming year, at the rooms of the St. George's Club, Cavendish Square, London. We look forward confidently for this event, as likely to afford so much interest to the whole of the British Chess circle; and learn that in all probability several of the first French players will accompany M. Kieseritzky upon this occasion. It is to be stipulated that each party shall play the King's Pawn two squares in every game; in fact, the Livonian player is eager that the contest shall be entered upon so as in every way to gratify public taste, and serve as a stimulus to the extension of Chess-practice; by setting up models of brilliant play. M. Kieseritzky is already well known in England, by the high reputation he has acquired, as one of the first Chess-artists of the day. He has played with M. St. Amant; and the result was strict equality. His style is that of Mr. Cochrane ;—dashing, bold and chivalrous; conducting endings of games with mathematical accuracy. M. Kieseritzky may be assured that he will be received here with the hearty welcome due to his talent; and that our metropolitan amateurs will spare no pains to render his stay in England agreeable to him.

Although Kieseritzky was possibly among the best theorists of the coffeehouse players, an expert in openings and endings, he was overly fond of wild gambits and often accused of playing for the audience, preferring show over soundness. And he was, indeed, a showman and a capable blindfold player. In one particular blindfold exhibition he played against four opponents (at that time, a new record), announcing his moves in a different language for each board - French, German, English and Italian. He also invented a 3-D version of chess that had as little impact as his unusual chess notation creation (see below).

Kieseritzky and Daniel Harrwitz played a series of 15 games, both players blindfolded. Kieseritzky won convincingly by +11-3=1

For all his sociable tendencies, Kieseritzky has been described in the most unfavorable terms - "...of livid complexion, with melancholic and afflicted appearance."

Just as for all his chess victories, his play was sometimes criticized by his contemporaries -

With all his fine genius and extraordinary knowledge of the game, Kieseritzky was the most wayward and crotchety of players. It was this and his constitutional timidity, perhaps, which prevented his occupying the highest place amongst the chess masters of the day. In his Openings he delighted in all sorts of odd, out-of-the-way manoeuvring. In his End-games, when the road to victory lay plain and direct before him, he would turn aside, as if from sheer wantonness, and lose himself in some inextricable maze, while his opponent took time and heart and reached the long-despaired-of goal. These eccentricities have been set down to an obliquity of mind. I am disposed to attribute them in part, at least, to another cause. He entertained a great repugnance to giving odds, and as his opponents were, for the most part, immeasurably inferior to him both in skill and bookish lore, he could of course afford, when playing "even" with them, to risk a good deal. Of what import was the loss of a few moves or of two or three Pawns to one who felt he was a Rook stronger than his adversary? It was thus probably that he acquired that fondness for rash attacks, and whimsical defences, which injured his game and told against him so terribly when he came to cope with men of mettle like his own. - Howard Stanton, "Chess Praxis"

Labourdonnais died in 1840. This was very shortly after Kieseritzky arrived in Paris. The two men did play together during their brief acquaintance.

DE LA BOURDONNAIS AND KIESERITZKY.

The two games between De La Bourdonnais and Kieseritzky, that we have given in our September and October numbers, will recall to the minds of our readers too vividly the loss that the Chess circles of Europe sustained when those distinguished players were taken from us by the irreversible stroke of death. Seldom or never do we meet with such specimens of skill as those which the eminent men whom we have named contributed to the literature of our game. Each, in his best day, was the ornament of Chess in France. De La Bourdonnais, succeeding to the throne of his predecessor, Des Chapelles, raised the renown of French Chess to a higher pitch than it had reached even during the legitimate reigns of Legalle, the half-British Philidor and Verdoni, or during the short-lived usurpation of Mouret, the regent of the Automaton. Kieseritzky,, although not by birth a Frenchman, was one of the ablest successors whom De La Bourdonnais, with the instinctive prescience of genius, raised up during his life, as worthy at a future time to maintain the excellence of Chess in France, and with it of Chess throughout the whole of Europe.

In the present article we propose instituting a brief comparison between these great masters of combination. De La Bourdonnais was gifted with moral and physical qualities of a higher order than those which were possessed by Kieseritzky. Not in the furnace of the Chalybes was tempered truer steel than that around the breast of the lion-hearted hero. His master-spirit knew not fear. It was through his unshrinking courage that his boundless resources perished not by an untimely blight, but were brought to their full maturity. It was this that enabled him to compete successfully with players of every style, from every country. Through this he was more than a match for the depth of Des Chapelles, the subtlety of Szen, the accuracy of Popert, the judgment of Slous, and the uniformity of Walker. Without this the French Hannibal could not have encountered, far less have obtained the victory over, generals inspired by genius and boldness not inferior to his own—the fiery and impassioned Cochrane, the sword — the undaunted and persevering McDonnell, the shield—of English Chess.

Kieseritzky was deficient in nerve. His constitutional timidity, that suffered many a conquest to be torn from him, debarred him from retrieving a defeat. This was the evil eye that bewitched him, that rendered him powerless for playing matches. He laboured under constant depression. The removal of his armour gave him no relief. His whole career justifies us in applying to Chess the criticism of one of the greatest masters of the human heart that the world has ever seen, when pronouncing judgment on a subject of far higher importance. “ The art of the orator,” says Demosthenes, “lies firstly, secondly, and entirely, in delivery.” So it is with the Chess-player. Without the power of expression, knowledge, however acquired, is fruitless, genius unavailing. But Kieseritzky atoned for his timid bearing by his modesty. In him we saw the genuine diffidence of a plain and unassuming man, not the pitiful cowardice of a vain-glorious boaster, who is conscious that if brought to the test he will be stripped of his borrowed plumes. He never displayed arrogance ; he was not

A monster filler with insolence and fear --

In tongue a lion, but in hear a deer."

De La Bourdonnais had other qualifications that gave him the superiority over Kieseritzky. A little deeper, he was entirely free from crotchets of every kind. Nothing could be finer than his play—nothing, at the same time, could be more practical. Prone to the carelessness of genius, he was never the spoiled creature of self-will. The combinations of other great players have been equally profound, but there is a difference in their elements. They are elaborate—De La Bourdonnais is distinguished for his simplicity. From moves of the most ordinary character, he discloses the most beautiful and unlooked for positions— with other players the first move is the key of the combinations. There is, notwithstanding, an intimate connection between his premises and their conclusion. Conceived in the highest spirit of poetry, his games will bear the examination of logical acuteness and mathematical precision. Kieseritzky was a crotchety player. With the obstinacy, but without the compensating boldness, of McDonnell, he would cling to untenable defences of openings, and pronounce them indestructible. In spite of this, we must, strange to say, declare him superior to his illustrious master in theoretical knowledge. The Pawns he played, if not with the vehemence with which De La Bourdonnais brought them up to assail his adversaries’ entrenchments, with more unerring certainty in endgames. What, however, was this in practical play, when compared with his favourite but weak defences to the Evans’ and K. BIshop’s Gambits? Thus theory is self—destroying. He who loves that which he himself has either invented or adopted, will succumb to the lover of what is true and practical.

In blindfold play both of them were distinguished, and far surpassed the legendary prowess of Philidor. Perhaps the most wonderful feature in De La Bourdonnais’ play is the brilliancy of his blindfold parties. Many a player can conduct a game without the board coolly and steadily, but who, save De La Bourdonnais, under such circumstances, invented attacks profound in conception, brilliant in execution, and enduring upon analysis? Who but the Chess Grand-Master could have contested a game without the board against a player like Boncourt, with the remotest chance of success? Kieseritzky was, in games played without the board, inferior to De La Bourdonnais alone. In point of fact, his blindfold games appear to occupy the same relative position to those of De La Bourdonnais, that his best games played over the board do to the immortal victories gained by his master over McDonnell.

As writers, these admirable players do not deserve the highest praise. Kieseritzky, if his invention of problems be thrown into the scale, may fairly be allowed the pre-eminence in this department of Chess. In the days of De La Bourdonnais, the periodical literature of Chess was not established on a firm footing—it was in its infancy. It was not sufficient to stimulate the powerful genius of the illustrious Frenchman. Great as he was in his ideas, and correctly as they are traced out, he would, we suspect, had he seriously directed his attention to the study, have obtained as much celebrity in the analytical as he has in the practical history of our game—B.

One of the two games mentioned in the above article.

(The first one, not given here, was a 56 move draw.)

In 1849, Kieseritsky started publishing his chess periodical, "la Régence."

Correspondence between Kieseritzky and von der Lasa reveals Kieseritzky's shaky financial footing. In 1850 the planned rennovations of Paris included the tearing down of the Café de la Régence, Kieseritzky's "workplace" as he called it. The failure of his magazine the following year and the likely disruption in his regular income most certainly weighed heavy on his mind. In 1851 he was invited to London to play in the first international chess tournament. Kieseritzky was one of the favorites. In spite of the fact that he had just beaten Anderssen convincingly in a match, his showing in the tournament was dismal with his first game, which lasted only 20 minutes, being the worst loss of his long chess career:

About this game Staunton wrote: "not only playing away the only piece guarding his King from mate, but doing it in such a manner that his opponent (even if he missed the mate) could still have won his Queen instead - a sort of double-barreled blunder that I have never seen equaled even among beginners of the game."

Kieseritsky, the favorite, was knocked out in the first round 0-2=1.

From here everything went down hill. After the Tournament, Kiesertizky furthered Anderssen's fame and ensured his own questionable place in chess lore by publishing another loss, a skittles game, to Anderssen played on June 21, 1851. When Ernst Falkbeer re-published the game in his very short lived Austrian chess periodical, "Wiener Schachzeitung," he christened it "Anderssen's Immortal."

Below is the game as it appeared in Kieseritzky's own publication, "la Régence" in July, 1851. It should be noted that the game was never played through to mate, as it's always given, but that Kieseritzky resigned after 20. Ke2 when Anderssen's clever plan became clear.

1) See Games II, XI, XIX, LXXUI, LXXIV, LXXX, LXXXV,

XCII, CIII, CIV, CV, CXVI, CXVII, CXXVII, CXXVIII, and CXXXV

CXL.

2) White has only two ways to save the Rook, namely, E-25 and G-48,

because by playing E-17 he would the lose the Bishop by D-62-X

3) This is not the best move; he should play g-67, and if then

White plays 37-g, it's answered by F-75.

4) From this moment White's play is superior.

5) Instead of taking the Bishop that White had left skillfully

en pris, it would be much better to push for d-64

and get rid of the Knight as soon as possible.

6) The only move to save the Queen

7) Perfect combination

8) Taking the Pawn and the attacking both Rooks is too tempting to resist.

9) The coup de grâce, which negates all efforts of the opponent.

This game was conducted by Mr. Anderssen with remarkable skill.

L. K.

The Immortal game as usually presented:

Two years later, at age 47 - the same age as Morphy when he passed away - Lionel Kieseritzky would die, penniless and friendless in the Hotel du Dieu in Paris, referred to as le Hôpital de la Charité, a place for the care of the insane, and buried in a pauper's grave.

Lionel Kieseritzky's obituary in the 1853 "Chess Player's Chronicle"

While the "British Chess Review" (ed. by Daniel Harrwitz who, himself, was a noted blindfold player) wrote:

It is with feelings of deep regret that we have to announce the decease of one of the most eminent players of Europe—M. Kieseritzky. It appears that he had been labouring under mental derangement for several months, which may partly have been caused by the too frequent practice of playing " blindfold," for which he was so celebrated.

"La Régence" was a very straightforward chess magazine that was light on talk and heavy on games. But it had one striking and unusual feature - one that might have contributed to it's early demise. Kieseritzky, for some reason, used an exclusive and somewhat bizarre notation to present the games in the periodical.

He gave the "key" to his notation in the frontispiece -

Note that the ranks are numbered 10-80 and the files 1-10. Each square has it's own number, much like the coordinates used in algebraic notation. The number is arrived at by adding the rank and the file. So, a1= 10+1=11; a2=20+1=21; b1=10+2=12, etc. This absolute notation was a far cry from the relative descriptive notation in vogue at the time.

The pawns are denoted by lower case letters a-h, while the pieces correspond to the upper-case letters that occupy their square in the "key."

Here is a game between Kieseritzky and John Schulten who was visiting Paris that year.

[X denoted "check;" XX denotes "mate;" hyphen (-) denotes capture]

An example:

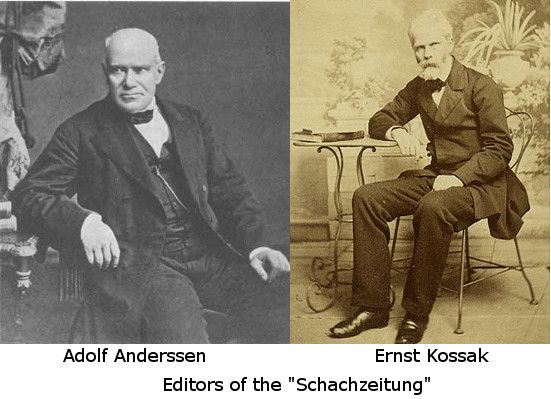

In 1853, upon the death of Lionel Kieseritzki, his obituary was published in the periodical "Schachzeitung" which was co-edited by Adolf Anderssen and Ernst Kossak. Kossak was disappointed with the dearth of information he had to work with and contacted Lionel's brother, Guido, in Dorpat requesting more details. In 1855 "Schachzeitung" published the fruits of this effort and we get to know a little more about our subject. Guido, whose words form the first part of this memorial, seems somewhat more interested in a bit of self-aggrandizement than in talking about his brother:

(a special thanks to member, Dirty_Sandbagger, for translating this from the original German and for some insights into the German culture.)

Lionel Adalbert Bagration Felix Kieseritzky (correctly Freiherr von Koseritz of the Holy Roman Empire and Polish Count Kizericki) was born in Dorpat on December 20th 1805 (January 1st 1806). He was the youngest - 14th - child of Otto Wilhelm Kieseritzky and his wife Catherina Felicitas née Hoffmann.

Lionel started at the same time as me (Guido), the next youngest child, to play with Chessmen, for you cannot call it anything but that, when our father asked us to mate him in three moves with Queen and Bishop. Back then, Lionel was three years old. From our older brother, Felix, back then probably the best chess player in Dorpat, we really learned to play the game. He gave us Queen odds at first, then rook odds, then soon only two pawns. When we were "Tertianer" in the Gymnasium, we did not receive any odds anymore because it had become obvious that both of us younger brothers were already a little better than the older one. When Baron Franz von Ungern-Sternberg, who was also well known as a painter, who played a lot with Allgaier, visited us, I dealt him a bad blow in the one game we played.

I played the Queen's Gambit and Ungern wanted, somewhat overconfident, to get the action back to he King's side, which I declared to be impossible. Ungern lost the game in a ignominious way. Lionel played with him more often and always won the majority of games, so Ungern acknowledged him as a better player. - In 1819 we both entered the Gymnasium of Dorpat, and in 1825 Lionel matriculated as a student of law at the University, which he left in 1829. He worked several years as deputy notary in the local court of Dorpat and during that time he became a director and soon also a factotum of the "akademische Musse" (the Academic social club) where he resurrected their old chess club from 1821. From those initial members who played at the start on October 11, 1821, I (Guido K.) am now perhaps the only one remaining. The names of the participants from back then are: Felix Kieseritzky, Andreas von Löwis of Menar, Guido Kieseritzky, Major von Hüene, Lionel Kieseritzky, von Sucknij.

Lately, the two of us rarely played against each other, but when be did, something strange occurred. Although in general Lionel played better than me, I still won nearly every game between us nearly without exception. The reason was that every time I was lucky enough to make a move that got Lionel out of book play which he was a lot better at than me. Once the game was going without one being weaker than the other, I usually had the advantage, that I, being his superior in creativity, (Herr Guido Kieseritzky is as excellent a mathmatician as a creative poet and a very strong player, especially in the middle game and the ending. He is unfamiliar with the theory of many openings though. -A. Anderssen) managed by exchanges to be one pawn ahead of him every time, and among the both of us, whoever was a pawn ahead necessarily won the game usually

In June 1839 Lionel left Dorpat and traveled from Riga to Rostock, via le Havre to Paris. In "Le Palamede" Labourdonnais soon considered him to be special: "Mr. Kieseritzky, a very strong young Russian". After Labourdonnais' death a short while after this, only St. Amant remained as an opponent of equal strength for Lionel in Paris. But his haughtiness regrettably caused an enmity between him and my brother, which unfortunately! lasted until St. Amant went off to America.

So far the words of Mr. Guido Kieseritzky. In the year 1832, as a student [Kossak would have been 18], I [Kossak] became a member of the "akademische Musse" in Dorpat, where I found several chess players who all were a lot weaker than me. Soon the beaten players presented to me Lionel Kieseritzky, who was considered the Grand Master of Dorpat's chess players, as my next opponent. I have a lively recollection of him as pale man, his head angled a bit to the front, simple hair and a lively, energetic gait. Our first match took three hours. Four games we played, of which I lost the first and the third one, had a draw in the second one and won the fourth one (Three of these games were written down during the same evening by me and I have kept them until now -23 years later. The second game, a very long one which remained a draw, was a Queen's Gambit which I played, but I could no longer write down.). From there we played weekly for several years with changing success, although in total, Kieseritzky was stronger. The gambit that was later named for him, then the King's Gambit Accepted Cunningham Defense, the Bishop's Opening and the Latvian counter-gambit were my opponent's favourite openings. The next strongest player after us was Lionel's brother Guido, but he neglected theory and analyzing because as a poet and mathmatician he had other pursuits. Later a certain Hehn [the aforementioned Major von Hüene?] proved to be a quite strong player. The rest were weak although a lot of chess was played at the "akademische Musse" and occasionally stronger players who were traveling came by to play.

As a person, Lionel Kieseritzky was amiable, full of wit and jocular. He had an immense talent for the theater and was excellent in comical roles. But often he was also peculiar, an eccentric even, which seems to be a trait of the Kieseritzky family and the culture of their chess, as several of them are strong players. I am only talking about the Kieseritzky of 1832-38 here, how I knew him in Dorpat; later, as a naturalized Frenchman he may have been quite a different person.

Like every chess player, Lionel Kieseritzky had good and bad days. On a bad day, he played much weaker than usual, sometimes even surprisingly bad. It is a strange thing with those "bad days". One can feel well disposed for a game, feeling healthy and well, but play like "une mazette" without ever being able to tell why. The more one tries to concentrate, the worse it becomes. Occasionally several days pass like that before one gets back on track. This occurrence has analogs in in poetry, fencing, riding, dancing, playing billiard, one can even be more disposed to talk in a non-native language during some days, without ever being able to name a clear reason. Therefore I cannot agree with anyone who laughed when Staunton struggled with such adverse fate against Anderssen and Wyvil at the tournament in London and claimed "he had not been disposed towards the game and unable to play." On the contrary, I firmly believe Mr. Staunton really has "bad days", just like Kieseritzky may have been influenced by one of these back then. In no way, though, would I wish in any way to detract from Mr. Anderssen's wonderful play by saying that.

Lionel Kieseritzky is dead, but among those who knew him, and in chess literature, he made for himself a lasting monument, and for a long long time enthusiasts of the noble game from all over the world will follow his gambit.

"This variation of the King's Gambit dates to Polerio (about 1590). The Italians, long before Kieseritzky's time, called it the Gambetto Grande: it was well known in the sixteenth century." (H. J. R. Murray, "British Chess Magazine.")

"This is the Gambetto Grande of the Italian writers. The numerous lines of play available for both attack and defence, make it a tolerably safe opening between equal players, while the complications that spring out of irregularity of arrangement add to the chances of the more skilful or more practis\ced player." (Freeborough and Ranken, "Chess Openings. Ancient and Modern." )

"If Black plays 4...Bg7 he consolidates his King's Pawns. To obviate this, White plays now 4. h4" (Hoffer, "Chess."— "The Oval Series of Games." )

"The object of 4. h4 is to avoid the usual sufficient defences, especially those in counter attack so frequently arising from 4...g4. White plays adventurously, and so, perforce, does his adversary. But, as in all cases of Gambit attack, the defence rests on surer ground, and is the more likely to succeed." (Mason, "Principles of Chess.")

"At one time this used to be the favourite Gambit. The late Dr. Zukertort did a great deal to combat the attack in this Opening, and in the Vienna Tourney of 1882 he administered the coup de grace by defeating Steinitz." (Gunsberg, "The Chess Openings."—" The Club Series of Games.")

"This Gambit maintains its position, and is likely to continue to do so, as a most popular Opening. It abounds in interesting situations, and some of the most beautiful games on record have resulted from it." (Bird, "Chess Practice.")

"The adoption of this Gambit, in contests of a serious nature, is, in these days, of rare occurrence." (Anthony Guest, "The Morning Post." )

notes: 1. "He was supposed to follow his father as an advocate, but instead he became a

teacher of mathematics." - OCC contradicts what Guido and Kossak say: that

Lionel studied law and became a Notary, and that Guido was a mathematician.

2. Blindfold results vs Harrwitz - "Blindfold Chess" by Eliot Hearst and John Knott

3. Kossak didn't sign the "Schachzeitung" article, but it's obviously attributable to

him, not Anderssen.

4. Kieseritzky's live chess production prior to leaving Dorpat, as well as mention of

his piano skills came from "Crescendo of the Virtuoso" by Paul Metzner, whose

own sources were a sketch by Friedrich Melung in "Baltische Schachblätter","

1890, by Bachmann in "Aus vergangenen Zeiten" vol. 1, 1920,

and in "La Régence,"1849-51, Kieseritzky, ed.

5. In 1853 "Schachzeitung" published a short evaluation of Kieseritzky as a chess

player followed by:

Kieseritzky starb im kräftigsten Mannesalter, ohne Anverwandte zu hinterlassen,

in einem Hospital, la Charité, und wurde von den Pariser Schachspielern

bestattet. Erst später bemerkte man, dass er einige Gegenstände von Werth

besass, welche die Kosten hinlänglich hätten decken können.