Like a Jewel

Reporting the death of Adolf Anderssen, on April 12, 1879, "The Saturday Magazine" wrote:

Paul Morphy has a world-wide reputation, and he deserves to have it, because he simply mowed down every one he came across;—but if the fame of Morphy be analyzed it will be seen that his victory over Anderssen in 1858 weighs more with chessplayers than all his other triumphs put together. Morphy's brilliant career lasted only three years. He was not heard of before, nor has done anything since, but during that brief period he was found invincible by whoever dared tackle him, and therefore his reputation will undoubtedly last until the New Zealander come, if chess endure so long. Nevertheless, if fame is to so meted out according to a just and impartial judgment, Anderssen, with his career of thirty years, during which time he has been dreaded by the strongest experts of two generations, must be looked upon as a greater chess-player than Morphy. The latter might have done as much if he had tried, but he did not try. He came before us in 1857, and he retired in 1860; but Anderssen lived and died a fighting chessplayer, and it is a proof of his undiminished greatness that no more, when threescore years had rolled over his head, than in his youth, could the strongest expert of the day afford to hold him cheap.

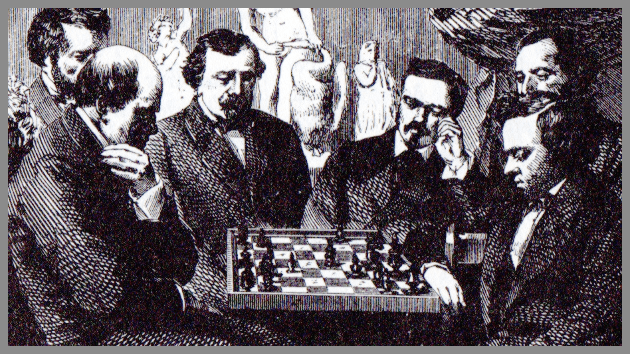

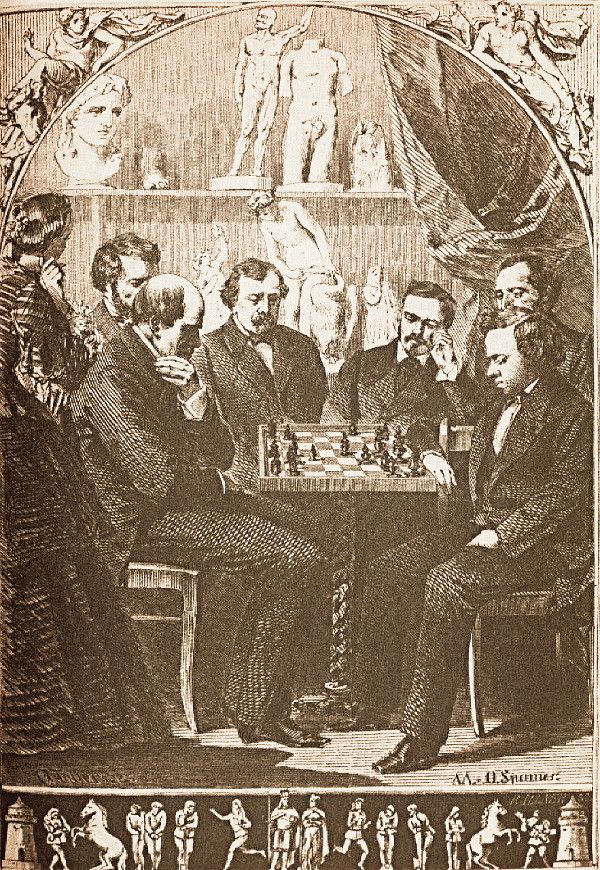

this image is from a woodcut published in Frederick Edge's "Exploits of Paul Morphy"

this image is from a woodcut published in Frederick Edge's "Exploits of Paul Morphy"

Adolf Anderssen's meeting with Paul Morphy is often fraught with misapprehensions. This article hopes to examine the details and shine some light into the darker dusty corners.

In the year Paul Morphy was born, Karl Ernst Adolf Anderssen (Max Lange called him "Adolphus Anderssen"), had already entered the university, studying mathematics and philosophy. His primary chess interest at this time was in the area of chess problems, creating as well as solving. He published a book of 60 original problems, "Aufgabe für Schachspieler," in 1842 (see "Anderssen als Problemkomponist"). As a regular of the Nova chess club/coffee-house in Breslau, he tested his skill (mostly unsuccessfully) against the likes of Ludwig Bledow, Heydebrand v.d. Lasa and, on at least one occasion, Johann Löwenthal. Wanting to improve, Anderssen spent time studying chess authors, particularly Bledow's translation of Lewis' annotated collection of the Labourdonnais-M'Donnel match, Moses Hirschel's translation of Greco, Johann Allgaier's "Neue Theoretische-praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiel" and Philidor's "l'Analyse," but was often forced to put aside chess and concentrate on his studies. It wasn't until 1847 when he became a private teacher in the village of Groß Machmin at age 29 that he started a more intense involvement in chess by making the very long journey to Berlin several times and playing against the best that German chess mecca had to offer. Morphy was, at this time, 10 years old and a recognized chess prodigy. Anderssen's efforts paid off and his successes started to mount, leading to his appointment as editor of the "Schachzeitung der Berliner Schachgesellschaft " after Bledow, its founder, passed away. This position, along with his continual successes earned him an invitation to the international tournament to be held in London in 1851. Around Eastertime in 1851 Anderssen resigned his easily-replaceable private teaching position and trained for several months in Berlin against Jean Dufresne and Ernst Faulkbeer in preparation for his depature for London in June. The Berlin chess community raised the funds, through buying shares of his possible winnings, for his journey.

The London international, one of the earliest of tournaments, was a knockout event. Even though many of the stronger participants were eliminated at the start, Anderssen's win was well-deserved. However some irregularities involving Anderssen existed. First, in order to facilitate his participation, Howard Staunton, from his personal funds, promised to reimburse Anderssen's expenses should he fail to win enough to cover them - despite the fact that the Berliners also assisted Anderssen financially; second, Anderssen entered into an agreement with József Szén that, if either one of them won, he would give the other one third of the winnings. Wikipedia claims: "this does not appear to have been considered in any way unethical" but it does seem to have been considered irregular and unbecoming a champion. Major Carl Jaenisch of Russia wrote: "Why, did not Mr. Anderssen himself, in a moment of trepidation, enter into an arrangement with Mr. Szén, that if either of them was lucky enough to gain the first prize, he should pay to the other one-third of the amount? Was not this an extraordinary piece of conduct for a " Chess King," if he have seriously accepted the title which ill-judging admirers have decreed him ?" Jaenisch was writing a response to an editorial penned by Otto von Oppen, editor of the "Deutsche Schachzeitung," in which he (unjustly) attacked Staunton for his words about Anderssen and for depriving him of the proper prize amount. It's not clear, but it seems the prize money, reduced through the agreement with Szén, also reduced the amount the Berlin subscribers would receive and inspired von Oppen's vitriolic attack.

After Anderssen returned home he took a permanent teaching position teaching German and Mathematics with Friedrich-Gymnasium (College) in Breslau, one he held until retirement (he was awarded professorship in 1856) but one that Emil Schallopp (whose biography of Anderssen in "Der schachkongress zu Leipzig im juli, 1877" is the basis for most of this information) considered a major factor in his loss to Morphy in 1858 since his ability to travel as well as his contact with the best German players became more restricted.

Emil Schallopp

Emil Schallopp

Shallopp wrote:

...aber um die fernere Pflege der erlangten Spielstärke war es doch traurig bestellt, da eine ausgedehnte Berufstätigkeit ihm wenig Muße ließ und es an ebenbürtigen Gegnern fehlte. Hierin ist der Grund zu suchen, weshalb Anderssen im Dezember 1858 zu Paris dem amerikanischen Meister Paul Morphy gegenüber unterlag, wenngleich feststeht, dass das Spiel des deutschen Meisters sich durch größere Tiefe und Genialität vor der gleichmäßigen Geschicklichkeit des kaltblütigen Amerikaners vorteilhaft auszeichnete.

which either says or infers that Anderssen's play was more creative and winning than Morphy's and that Anderssen lost simply on weaker technique due lack of proper practice.

Max Lange echoed this opinion in his, "Paul Morphy; a Sketch from the Chess World":

Lately, Anderssen has devoted his leisure hours to private studies, whilst his only recreation, which is not of a literary nature, consists in a game of Chess, although amongst the members of the Breslau Club there is not one player of his strength. This want of practice with first-rate players exercised a greater influence, than Anderssen could or would have believed before, on his unlucky match in Paris.

But between 1852 and 1858 Andersen was hardly a chess hermit. He played a large, now famous, series of games against Louis Eichborne. He played the Berliner Pleiades' Karl Mayet and Heydebrand v.d. Lasa as well as Jean Dufresne, David Hillel (a strong player and professional chess teacher who "einmal dem berühmten Schachdorfe Ströbeck einen Thurm vorgab.") in addition to visiting England where he played Lowenthal, Mongredien, Harrwitz, Boden and Kipping.

Curiously enough, Anderssen lost to James Kipping -5+4 whereas when Morphy played Kipping, the 36 year old banker, the following year the score was +2-1 in Morphy's favor, the loss being a blindfold game in an 8 board simul. James Stanley Kipping was the secretary of the Manchester C.C. and considered among the strongest English amateurs of the day.

[As a side note, his grandson, Cyril Stanley Kipping would earn the honorary FIDE title of International Master of Chess Composition in the 1959.]

Without completely gainsaying Lange's and Schallopp's contention that Anderssen was out of practice since it's probable, at least compared to his exposure just 5 or 6 years earlier, that he was less practiced, the implication that this gave him a disadvantage against Morphy —or as Schallopp suggests, it was the prime cause for the loss— is highly improbable given what we know about Morphy himself.

Paul Morphy never really studied chess, relying on his remarkable memory and natural intuition, nor did he train obsessively.

I send you herewith a game of chess played on the 28th instant between Mr. R[ousseau] and the young Paul Morphy, my nephew who is only twelve. This child never opened a work of chess; he learned the game himself by following the parties played between members of his family. In the openings he makes the right moves as if by inspiration; and it is astonishing to note the precision of his calculations in the middle and end game. When seated before the chessboard, his face betrays no agitation even in the most critical positions; in such cases he generally whistles an air through his teeth and patiently seeks for the combination to get him out of trouble. Further, he plays three of four severe enough games every Sunday (the only day on which his father allows him to play) without showing the least fatigue.

[Ernest Morphy to Lionel Kieseritzky, editor of "La Régence," Oct 31, 1849]

Morphy didn't produce a large catalogue of recorded games and, except for a brief period, he never played a great deal of chess either.

Paul Morphy was never so passionately fond, so inordinately devoted to chess as is generally believed. An intimate acquaintance and long observation enables us to state this positively. His only devotion to the game, if it may be so termed, lay in his ambition to meet and to defeat the best players and great masters of this country and of Europe. He felt his enormous strength, and never for a moment doubted the outcome. Indeed, before his first departure for Europe he privately and modestly, yet with perfect confidence, predicted his certain success, and when he returned he expressed the conviction that he had played poorly, rashly —that none of his opponents should have done so well as they did against him. But, this one ambition satisfied, he appeared to have lost all interest in the game.

[Charles Maurian in his obituary column for Paul Morphy in the New Orleans "Times-Democrat"]

When Morphy sailed to England, his reputation, stemming from his winning the American Chess Congress and a few published games, was considered far less than stellar since the Europeans sneered at the competition upon which his reputation relied. Whereas Anderssen had had years of practice with the best German players (whom the Germans themselves considered to be in a class above the rest of the world), Morphy's only contact with world-class players (other than his childhood encounter with Lowenthal) occurred after he arrived in England just 6 months prior to his match with Anderssen.

Morphy had first landed in England in June of 1858 where he tried in vain to get Howard Staunton to play the match that Staunton seemed to agree to in a letter and later in person. He played other English masters (particularly Löwenthal) while waiting for Staunton to fulfill his implied promise. Impatient with waiting in London and feeling he was wasting valuable time, Morphy traveled to Paris on the last day of August, where he beat Daniel Harrwitz, the well-known blindfold player. Although he had planned to go to Germany and meet with players like Adolf Anderssen, Carl Mayet, Max Lange and possibly even Heyderbrandt von der Lasa (who was, however, in Rio de Janeiro), Morphy, who had, according to Frederick Edge, "been an invalid since his arrival in the French capitol," who was becoming less and less enchanted with chess, completely avoiding the chess scene at the Café de la Régence for two months and who was being urged to return to New Orleans as planned, found he couldn't travel to Germany in his condition and was completely resigned to going home without playing Anderssen. It's turned out that his doctor, who dissuaded him from traveling to Germany also insisted he not make the steamer voyage to the United States.

But it was the general conviction in Germany that Morphy would never have left Europe without playing Anderssen. As Lange related:

It was clear that the American champion would be compelled to encounter the far-renowned German masters ere he could boast of the championship of the world. His chivalrous mind would have doubtlessly led him to that final and decisive combat; and the programme of his Chess tour, which was repeatedly announced in the American Monthly, distinctly intimated a similar project. Moreover, it would have been indifferent to the German masters that a foreign and newly risen Chess celebrity was gathering laurels in France and in England, as long as that knight errant of Chess did not consider it necessary and to the interest of his own reputation to enter the arena with those who were acknowledged the strongest.

The Germans were very secure in their sense of chess superiority and felt that any "rising star" seeking to enhance his reputation should make the overture of going to them. The Leipzig Chess Club (to which Max Lange belonged) and the Breslau Chess Club had both sent Morphy letters inviting him to play Anderssen at either venue. In the beginning of October, after all chances to engage Staunton had dissipated, Morphy replied that he couldn't come to Germany but would send Mr. Anderssen the 295 francs raised by the amateurs of the Café de la Régence for his expenses to come to Paris. To this Anderssen responded that he couldn't get away until his December vacation and countered by personally inviting Morphy to Breslau, offering a stake of £50 along with £25 for Morphy's expenses. Morphy replied (to Dr. Schutz, secretary of the Breslau C.C.) that he wasn't a professional, so stakes were out of the question and that he had his own funds, so expenses weren't an issue. Still maintaining he couldn't come to Breslau, Morphy ended his letter: "I had hoped he could accept the invitation of the French players, but the dispatch received Saturday deprives me of hope that I will be able to measure myself with the German champion."

Morphy had, in fact, planned on being in New Orleans by Christmas and even the prospects of a match with Anderssen wouldn't alter his resolve.

. Frederick Edge (Morphy's secretary and self-invited companion who wrote the book about his European tour) confirms this:

Herr Anderssen immediately replied, that his duties as mathematical professor at Breslau presented an insurmountable objection to his leaving, but that the Christmas vacation would enable him to meet the American player in Paris. Morphy said, thereupon, that he should be deprived of the pleasure of crossing swords with the victor in the International Tournament, inasmuch as he must be at home before Christmas. On hearing this, I began to talk the matter over quietly with him, asserting that his voyage to Europe was useless, if he did not play Anderssen. All was of no effect. Morphy did not appear to have the slightest ambition, say what I would to him. He must be at home in December; he had promised to be there, and home he would go.

Plans tend to go awry. Again according to Edge: "Our hero originally intended making a visit to the principal chess clubs of Germany, and especially to Berlin, but having been an invalid since his arrival in the French capital, he feared to undertake the long journey by rail..." His doctor had advised against making an extended winter ocean voyage in his condition so he couldn't go home and travelling to Germany, was out of the question.

Unknown to Morphy, Edge had started a letter-writing campaign to all the chess clubs in Europe asking them to entice Morphy to stay.

After a week or two, Morphy began receiving letters from Amsterdam, Leipzig, Brussels, Berlin, Breslau, etc. ; from the London and St. George Chess Clubs ; requisitions signed by the amateurs of the Café and Cercle de la Régence, expressing the earnest wish of all that he would remain throughout the winter. Herr Anderssen wrote him a lengthy epistle, in which he assured him he did not think it possible he could leave Europe without playing him, and adding is voice to the general cry.

As noted, Anderssen agreed to come to Paris. Morphy's affliction, however, took a turn for the worse and he was confined to his room since the beginning of December with what was termed intestinal influenza for which the treatment was a series of applications of leeches. The loss of blood left Morphy weak and unable to get out of bed. Around this same time Anderssen began his arduous journey to Paris and upon his arrival on December 15, was dismayed to find Morphy bed-ridden. Anderssen didn't want to start a match against such an ill disposed opponent but Morphy assured him that by Monday he would be ready.

It must be established that the Germans has several issues with this whole affair. First was Anderssen's agreement to come to Paris (for which Lange raked him over the coals in a long letter). Second was Edge's letter-writing campaign which they viewed as an underhanded tactic to entice Anderssen to go to Paris, assuming the role of the challenger. Third was Morphy's illness which they considered nothing more than a ploy. Writing to v.d. Lasa on Dec. 31, Anderssen stated:

Altogether, he is not only a great chess player but also a great diplomat and all maneuvers which he inaugurated in reference to me since his arrival in England had not other purpose than to lure me to Paris and to burden me with the inconvenience of the trip. Likewise, I admired from the very beginning as a very tactful diplomatic maneuver that he took to his bed when I arrived in Paris, and I have never changed my mind about that.

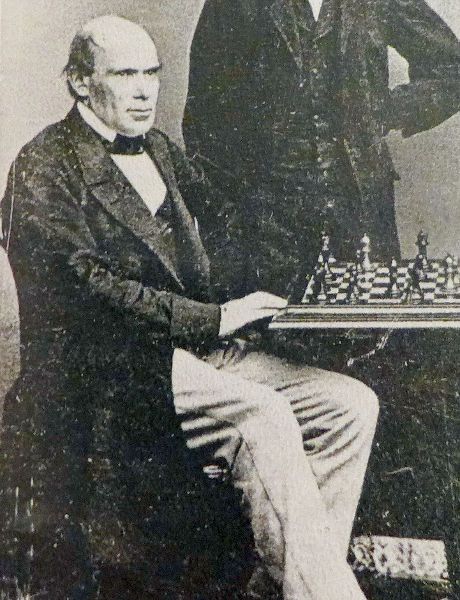

Anderssen in 1862

Anderssen in 1862

After briefly talking with Morphy, Anderssen and Edge finalized the match conditions — no stakes, first player to win 7 games — and walked to the Café de la Régence where Daniel Harritz was working. Morphy had just beaten Harrwitz in a set match that September. Harrwitz, like Anderssen, was from Breslau. Considered one of the strongest players in the world, he was especially celebrated for his blindfold play. Harrwitz and Anderssen were old nemeses. Their 1848 match, expected to be 11 games was cut short leaving the result at the inconclusive 5-5. Some good natured bantering about who was better off led to a series of 6 skittles games of which Anderssen won 3, lost 1 and drew 2.

Monday, Dec. 20 arrived. Early that morning Fred Edge and James Mortimer helped the unsteady Morphy out of bed to get him ready for the match which would begin at noon. The match itself was held in a special room set up iat the Hôtel de Breteuil on No.1 Rue du Dauphin where Morphy was staying and "where we had a magnificent view of the palace and gardens of the Tuileries, and were within a stone's throw of the best quarters of Paris and the Regency" [Edge]. Anderssen arrived promptly at 12:00; Morphy, appearing pale and weak, was a half hour late.

Besides the competitors, there were 10 (or possibly 11) observers:

Morphy's physician —was present for the first two games since his approval for Morphy to play was given against his better judgment.

Dr. Johnston —a correspondent for the New York "Times"

Eugène Lequesne —who sculpted a bust of Morphy,

P. Ch. F. de Saint Amant —Champion of France in the 1840s who lost his match with Staunton in 1943.

Jules Arnous De Rivière —one of Morphy's closest Parisian friends and probably the strongest French player at that time. He had played skittles with Anderssen while waiting for Morphy to recover.

Carlini —an artist living at 3 rue Chaptal and member of the Cercle d'échecs in the Café de la Régence,

James Mortimer —At the age of 22, this newspaper editor was appointed attaché of the U.S. Legation in Paris. He was 25 when he met Morphy. In his article "Chess Palyers I have Known," published in the "BCM" in May, 1905, Mortimer wrote:

"In my hours of leisure, I went almost every day to the Regence, to do a little "wood-shifting" with some mazette (duffer) of about my own feebleness, or occasionally to pay half a franc for the privilege of being beaten at the odds of Rook or Knight by any professional " artist" or strong amateur who would graciously condescend (for fivepence a lesson! to show me "how it was done." l was Morphy's fellow countryman, and four years his senior. He had arranged to make Paris his headquarters for a considerable time, and it was not long before we became intimate friends."

. . .

"In the following December was played the Celebrated match between Morphy and Professor Anderssen, then esteemed the greatest of European players. The score of this match was: Morphy 7. Professor Anderssen 2, and two drawn games. The match was commenced at the Hotel de Rivoli, where Morphy was residing, and I helped him to rise from a sick bed to play the first game—-which he lost."

[45 years after the fact, Mortimer confused the Hotel Breteuil with the Hotel Rivioli most likely because the Hotel Breteuil was located at the corner of Rues de Rivioli and du Dauphin. ]

Jean-Louis Preti —professional flutist-turned-importer and future editor of "La Stratégie." At hi death his son, Numa, edited "La Stratégie" until his own demise.

Paul Journoud —one of France's strongest players and also a member of the Cercle d'échecs in the Café de la Régence. About Journoud, Edge wrote:

"Monsieur Journoud, one of the best known and strongest of French players, and a member of the Paris Committee of Co-operation on the International Tournament of 1851, played upwards of a dozen games at different times with Morphy; but though he came very near winning on one or two occasions, our hero always wriggled out at last at the right end of the horn. Journoud once described his opponent's game as 'disgustingly correct'."

Journoud was better known for his journalistic efforts having edited "La Regence" in I860; "La Nouvelle Regence" 1861 to 1864; "Le Palamede Francais" during its first six months; "Le Sphinx" 1866-67." ["BCM" May, 1882]

Frederick Milne Edge - was an intriguing character. A British newspaperman working in New York, he met Morphy at the American Chess Congress in 1857 and attached himself uninvited to Morphy when he arrived in London. His book of their adventures in invaluable, even if, as Willard Fiske called it, it was "a gossipy account." He and Morphy had a falling out in Paris, possibly over the book, which sent him packing. Later Edge would act as a war correspondent in the American Civil War (one of only two English correspondents remaining in the war's latter part (Edge was working for the "Morning Star") and wrote many books, articles and pamphlets on social issues. His wife was also a social activist.

[According to Max Lange, a M. Grandboulogne was also in attendance as either a second or an official witness. Dr. Johnston never mentioned him in his report, but Lange was undoubtedly referring to "le docteur (Alphonse) de Grand-Boulogne," whom "La Régence: revue spéciale des échecs" in 1862 called, "un amateur d'échecs distingué."]

A few blocks away in the Café de la Régence, the crowd had grown so large that three boards were set up to allow everyone to follow the progress of the games with the moves carried by messenger every half hour.

After each game, Anderssen walked down to the Café de la Régence to expedite the transmission of the moves to both Leipzig and Berlin where his supporters waited eagerly for the results.

Illustration by Otto Spammer of Leipzig, 1859

(from a staged photograph taken on Dec. 29th)

Dr. Johnston reported:

Nothing could be more unlike than the physique of the two players. Mr. Morphy is a frail, small boy, with a fine face and head, and a modest, almost timid air. Prof. Anderssen, on the contrary, is a tall man, slim, about fifty years of age. with a small head, a slight stoop in the shoulders, lively black eyes, a clean-shaven face and a decidedly German cast of features. He is a quite gentlemanly man, with a sympathetic expression of the face, which immediately predisposes in his favor.

The following passage, also from Dr. Johnson, is rather interesting since Morphy is generally considered today to have been an extremely fast player and the Germans view of Anderssen's style vs that of Morphy is the exact opposite:

During the first game M. Anderssen moved much more rapidly than Mr. Morphy. Not a word was spoken by either player during the whole seven hours. No demonstrations or false moves were made by either party to indicate to the other his plans. There seemed to be more originality, more genius, more of the imprévu in Mr. Morphy's moves, and more of the study and experience in those of M. Anderssen. The two men are evidently more nearly matched than they ever were before.

Along this same line, in a letter to "Herr Von Heyderbrandt V. der Lasa" on Dec. 31, 1859, Anderssen wrote:

His figuring is, in general, not of remarkable or even tiring duration: he always takes as much time as such a tireless and experienced thinker requires depending on the position, but never makes the impression of useless and tormented pressure or stress - an impression I occasionally had with Staunton.

Interesting enough, Hans Renette, in his "H.E.Bird: A Chess Biography," quotes this passage from the Nov. 1932 issue of the "BCM":

[Oscar Conrad} Múller pointed out at a slightly negative point made by Bird:

'One afternoon Morphy turned up at about one o'clock and offered to play me a skittle game. I accepted the challenge, and the game actually lasted, owning to his slow play, till nine p.m., when I lost it.'"

Edge wrote:

On Monday morning, I got Morphy out of bed for the first time since his illness, and, at noon, assisted him into the room where the match was to come off. No time was lost in getting to work, and, within five minutes of his entering, as many moves had been played. Our hero had first move, and ventured the Evans’ gambit, which he lost, after seven hours’ fighting, and upwards of seventy moves. I noticed that he was restless throughout the contest, which was only to be expected after having been so long in bed, and without nourishment.

Morphy was charmed with Anderssen’s defence [sic] throughout, and has frequently cited it as an admirably conducted strategy. It proved to him that the Evans’ is indubitably a lost game for the first player, if the defence be carefully played; inasmuch as the former can never recover the gambit pawn, and the position supposed to be acquired at the outset cannot be maintained.

This was a remarkable admission since, out of about his 80+ recorded Evans Gambits , Morphy only lost 2 playing even and a few at Rook and Knight odds.

This first game - the Evans Gambit won by Anderssen - was possibly the best game of the match, belying the notion that Anderssen was out of practice.

The first five games featured 1.e4. Anderssen, after losing three in a row, completely abandoned that hallmark of Romanticism, opening his finale three games as White with 1.a3, evermore to be referred to as Anderssen's Opening. Even though he lost his first game with this opening, he managed to draw the second and win the third. The only instances of earlier use of this opening that I could find were 2 games by Kieseritsky: one a loss against Henri Boncourt and the other a draw against Saint-Amant in 1843.

As a curious side note, Anderssen played a series of games against the innovative future Dutch champion, Maarten van't Kruijs in July of 1861. Wining five and drawing two of the eight games, Anderssen's only loss was playing black against to van't Kruijs' 1. a3. Anderssen later used this opening with success against Louis Paulsen, George Mackenzie, James Mason and Adolf Schwartz.

Today the two most popular responses to 1. e4 are the Sicilian and the French, neither of which were popular with Romantic players. Morphy only played the French from the Black side twice, winning both games and only faced it a handful of times, winning all but for a draw with George Walker in a blindfold simul. The Sicilian Defense was very distasteful to Morphy - he called the fondness for this defense "pernicious." However, out of the 20 recorded games where Morphy played against the Sicilian, he won 15, drawing against Augustus Mongredien, Thomas Avery and Louis Paulsen and losing only when giving odds against Horace Richardson (at Kt. odds) and against Charles de Maurian (at QR+QN odds).

During his long chess career Anderssen had good results on both sides of the Sicilian.

Max Lange took Anderssen's improvement in results using 1. a3 as an indication of his superior genius:

An impartial and profound examination of the games in this match, proves, on the part of the vanquished, an uncommon depth in judging positions, and even shows him to be the superior genius in a certain class of games, in which that advantage predominates. That class of games which obliges each party to arrange first their pieces on their own territory, and thus exacts a long foresight of future positions, and a comprehensive understanding of Pawns and pieces in concerto, not having been as yet analyzed in books, gives free and full scope to the exercise of genius, and affords at the same time a proper scale for the appreciation of the natural depth of combinations. To the superiority of the German master in this class of games which is especially shown in the sixth, eighth, and tenth, and which he regrets not to have made use of sooner, the American can oppose his perfect knowledge and accurate play in all the open games wherein he has a nearly equal superiority, as Anderssen, entirely absorbed by his professional duties, could lately not devote so much time to the study of the openings, and therefore succumbed nearly always in those games, which are analyzed by the books and which form the great majority of the match.

Results Summary

White and Black squares indicate the players' pieces

White and Black squares indicate the players' pieces

In spite of this devastating loss, Anderssen, according to Lange, wouldn't admit Morphy's superiority:

He did not even in his dreams," he [Anderssen] said, " believe in the superiority of his opponent; it is, however, impossible to keep one's excellence in a little glass casket, like a jewel, to take it out whenever wanted; on the contrary, it can only be conserved by continuous and good practice."

In reading Lange's account, one gets the feeling that Anderssen felt that after the match he was treated with an air of condescension from those surrounding Morphy, though not from Morphy himself about whom he said "was invariably polite to him, but more so after his victory, and that he manifested his satisfaction by several little attentions. "

Anderssen said, "Those who surrounded the American, however, seemed to think that they flattered me most when they said, how high an opinion the American had of my play, and that he considered me the strongest of all opponents he had met till now. But to be reckoned stronger than a Löwenthal I consider next door to nothing! "

Lange summed up the German attitude concerning the outcome of the match:

It is evident therefore that the want of strong practice in the German master, which is so great an obstacle to success in similar matches, must have been strongly felt by him when opposed to the American, who, so to say, only lived for the practice of the game. In most of the games, we thus see the German player either through evident blunders, as in Games III., VI., and IX., or through mistaken easy combinations, showing the want of tension in his intellectual powers at the moment, as in Games IV., VI., and IX., or lastly through undervaluing his opponent's strength, as in Games IV. and V., throw an already obtained advantage away and lose the game. If therefore we take into account the specific quality of coolness, which is the peculiarity of the tough Englishman and the practical American, and oppose it to the depth of combination which, characterizes the German genius, we find that the balance is greatly ins favour of the American, by his thorough knowledge of the openings and their application to practical play, and that balance, too, is in full accord with the result of the match. To sum up our remarks, we can state in a few words, that at all events the American was, at the time, the superior, that is, the more practiced match player.

Twenty-six years later, Wilhelm Steinitz, stung by criticism of the quality of play in his world champion match with Zukertort, compared the play in that match with Morphy's play vs Anderssen, pointing out blunders, weak moves and poor strategy. While his motives were rather self-serving, his observations had merit.

A paragraph from his article is captured below for anyone who cares to read it:

It will, no doubt, he admitted at all hands that Anderssen was Morphy's strongest opponent and here is a brief review of the match between the two masters which please to examine carefully and report upon it in comparison with the games of the late match. In their first game. Morphy committed a serious strategical error, on the 14th move, which costs a Pawn and brings his Bishop out of play. 14 B–K3 was his correct move; Morphy apparently apprehended P-KB4 in answer, which was not dangerous by proper treatment. As it was, Morphy ought to have lost the game in a few moves, as Löwenthal proves, but Anderssen overlooked it and only won after a fight of over seventy moves. In Game II, Anderssen made an unsound sacrifice of a piece on the 23d move ; Morphy, as admitted by Löwenthal, overlooked an easy winning process and allowed a draw. In Game III, Anderssen, after a very weak 17th move, on the 19th move makes a fearful blunder, one which was enough to dishearten him for the whole match, for he loses a clear piece or the Queen by a simple combination only two moves deep. Löwenthal maintains that he had a lost game at the time, but I am fully convinced that he had at least an even game with a Pawn ahead if he had moved Q—Kt 3. In Game IV, Anderssen throws away a clear piece on the 23d move without a shadow of justification, for already Löwenthal proves that Morphy could have won the game in a very easy manner, six moves later, instead of which he throws away two Pawns quite needlessly, and I am almost certain that Anderssen could have at least drawn the game after that, on the 35th move, by Q-R8 ch. but he lost it. Game V, Anderssen could have at least drawn on the 20th move by Ktx B, and Löwenthal in his analysis to the contrary overlooks 22 Q—R7 ch., followed by KtxKt, threatening mate, but Anderssen lost it. In Game VI, Morphy's advance 11 P-KKt 4, was strategically a gross error which could have been taken advantage of in different ways even stronger than those Anderssen adopts who, however, also obtains a fine game which he could have won several times in the middle, but he lets his opportunities slip. In consequence of an at least premature sacrifice on the part of his opponent, Morphy had, on the 39th move, what I believe to be a won game by R–QB sq., instead of which he leaves himself, however, open to a sure draw which his opponent overlooks and loses a piece by an oversight. Game VII is one where the material advantage of a Pawn is given up by Morphy on the 7th move without sufficient cause and hardly for good reason returned again by Anderssen who, however, has still a little the better game up to the 16th move, when Morphy plays for winning the K R P and giving up the QBP for it, which would have been to Anderssen's advantage. But the latter being unjustly afraid of exposing his King, and instead of moving P-QKt 3, makes a very bad move with his Rook, on the 16th move, which brings him into difficulties. By another gross error, on the 20th move, he loses two Pawns, when he might have escaped with the loss of one, with a fair game for drawing purposes. Game viii, Anderssen could have won on the 39th move by R-Q5, followed mostly by Kt—QB4, but it ends in a draw. In Game IX, Anderssen, actually, already on the 8th move, by a plain oversight, subjects himself to the loss of the exchange. Morphy, instead of contenting himself with that easily-winning advantage, institutes an attack from which Anderssen might have escaped with the loss of a Pawn only, with a fair position, but the latter overlooks the right process, and loses on the 17th move [In the January 1885 edition of "The International Chess Magazine," Steinitz had called this game 'brilliant']. In Game X, Morphy commits a bad strategical error on the 29th move, and his game was already irretrievably lost in a few moves and in a very simple manner if Anderssen had played 34 Q-Kt 7 instead of exchanging Queens. However, two moves later, as Löwenthal justly remarks, Anderssen overlooks a fine and complicated winning combination, while Morphy afterward, on the 42d and 58th moves, misses his opportunities of drawing, and loses ultimately. In Game XI, which is the last of the match, Anderssen's 20th and 22d moves are flagrant errors of position judgment which could have been easily avoided.

["The International Chess Magazine.", May, 1886. p.116]

All the match games can be seen here.

Anderssen in 1863

Anderssen in 1863

On the 29th, the day after the match ended, Morphy and Anderssen played a 6 game skittles match (the entire match lasted 3 hours), all King's Gambits, which Morphy won 5-1.

Skittles were off-hand games usually played quickly although there were no clocks. One of the most famous games of all time was a skittles game won by Anderssen against Lionel Kieseritzky on June 21, 1851. This game, known as The Immortal Game, occurred within a series of skittles games played between the two men during the Grand Tournament. Anderssen's winning result vs Kieseritzky in the tournament itself was a +2=1. The more lengthy skittles series was won by Kieseritzky +9-5-2. The Immortal Game was one of Anderssen wins.

Here is Anderssen's one win from his skittles match with Morphy:

Anderssen left for home on January 2. Morphy stayed in France until April 6 when he returned to England to catch a steamer for the U.S. Morphy may have been planning to visit Germany —Anderssen seemed to have that impression when he stated "They wont be pleased with me in Berlin, but I shall tell them, 'Mr. Morphy will come here himself." — or he may have just been waiting for the more benign Spring weather. At any event, his mother had requested his brother-in-law John D. Sybrandt, who had gone to Europe on business, to hurry Morphy's departure, in effect suppressing any plans he might have had to stay longer.

This meeting, however highly anticipated, was hastily arranged, full of misunderstandings, suspicions, machinations and misrepresentations. Both Morphy and Anderssen conducted themselves with great propriety however, rising above the situation. Max Lange illustrated some of these misrepresentations in his book on Morphy:

The match with the American began on Monday, December the 20th, and was continued without intermission. Besides these chief games, there were played a few off-hand contests, to which, however, Anderssen attached no importance whatever. They met for another distinct purpose, but the preparations were, through mistake, not finished; and just in order to pass the time, a few games were played in a skittling style. Afterwards, great emphasis was laid upon these games by French and English writers; often, also, the most innocent expressions, which sometimes had quite a different meaning, or were spoken occasionally by the German player, were laid hold of, and undue importance attached to them. Amongst these may be mentioned the words attributed to him, "that it was a rare fortune for a player to win one or two games against Morphy." The fact is, that at dinner, before the last game was played, Anderssen said, jokingly and in good temper, " He was glad to have already two sheep in safety." Again, Anderssen is reported to have said, " Il joue non seulement le coup juste, mais le coup le plus juste." (Morphy makes not only the best, but the very best move.) " No living player has a chance in play against Morphy ; it is uncertainty struggling against certainty."

The truth is, that Anderssen only spoke of the great correctness of Morphy's play, and simply remarked, that the American never made a mistake, and very rarely an error.

Harold James Ruthven Murray summed it up in his 1913 tome, "A History of Chess" —

In the play of Morphy and Anderssen the principles of the Lewis school reached their highest development. Both were players of rare imaginative gifts, and their play has never been paralleled for brilliancy of style, beauty of conception, and depth of design. In Morphy these qualities blazed forth from sheer natural genius; in Anderssen they were the result of long practice and study, the foundations being laid in the composition of the problem.