Ian Nepomniachtchi FIDE World Championship Interview

GM Ian Nepomniachtchi is making his second attempt at winning the FIDE World Championship and is just three draws away from becoming champion.

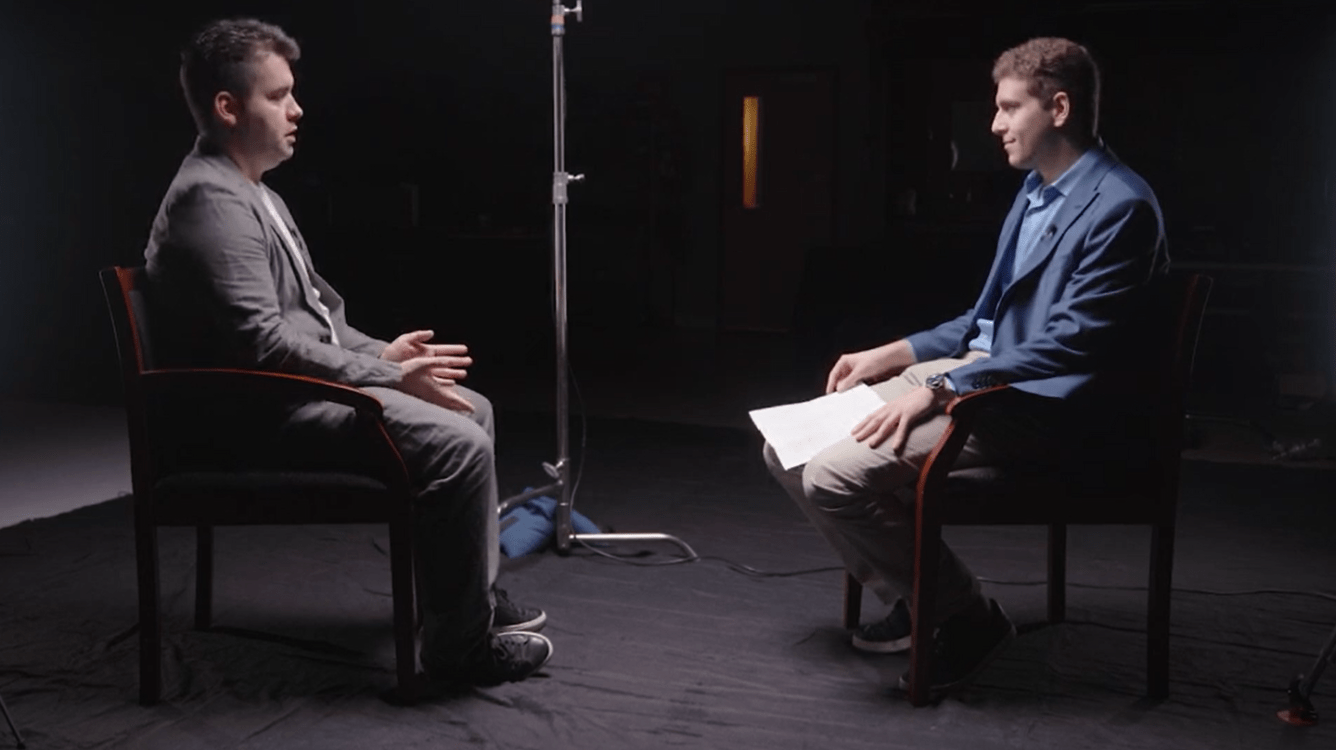

During last year's Sinquefield Cup, Nepomniachtchi sat down with Chess.com's GM Daniel "Danya" Naroditsky to discuss his early chess career, his chess philosophy, the championship match, his opponent GM Ding Liren, how his preparation changed once GM Magnus Carlsen announced he would not play the match, what he learned from his previous FIDE World Championship, and more.

What follows is the transcript, including short video excerpts.

- Upbringing

- First Success and Making Grandmaster

- Progress to 2700

- Chess Engines

- Rapid & Blitz vs. Classical

- Chess Commentary

- Candidates Tournament 2020

- World Championship 2021

- World Championship 2023

- Conclusion

Upbringing

Danya: Ian, thank you so much for taking the time out of your day during this very, very demanding tournament and joining us for this interview [ed. note: Nepomniachtchi was playing in the Sinquefield Cup at the time]. Let's start with the basics. When did Ian Nepomniachtchi learn how to play chess? Who was your your first trainer? When did you realize that this is getting serious?

Ian: Well, thank you for inviting me to this interview at all. First of all, I think my story is quite regular. So when I was about four years old, I was introduced to some chess pieces, but it was more like some soldiers. It was a quite unusual chess set. So I would play with a lot of different stuff, imagining some of the key pieces.

At the same time, there was another, let's say regular chess set, and my uncle and I played quite a lot. I think my grandpa was a second-category player or something, or maybe even first-category, in Soviet terms, which is quite something.

And my uncle is a master candidate and they spent quite a lot of free time playing each other. So it's quite usual stuff for the former Soviet Union and for Russia as well. At some point, I was like, "Okay what are you guys doing here?"

And that's how I was introduced, and I think I was about four and a half. And also, maybe later that year, the local chess club was constantly moving here and there, and it moved quite nearby to basically our block. So it's five minutes walking.

Danya: That's convenient.

Ian: Yeah, quite near. So they decided to show me to a chess coach, also I think a master candidate. He said "yeah, of course." And that's how I went. I think I was maybe five, maybe I was slightly younger, maybe almost five.

And there I met my first coach, FM Valentin Evdokimenko, who is just an incredibly kind man and gentle, especially with children. So that's just what the doctor prescribed. And I think it was a great fortune in my life. The first coach is very important. It's someone who really guides you into the world of chess. And I think quite soon he wasn't only having these classes with me in the chess club, but he also was visiting us, and...

Danya: He became a friend.

Ian: Of course, a friend and mentor, and also I would say that a few years later, he did something which I don't know a lot of examples of. When he felt that he couldn't truly help as much as before, he spoke to international master Valery Zilberstein, who was two times Russian champion in Soviet times, maybe he would be interested to work with me. I believe it was a huge milestone, and also I would say that it's just quite impressive. Because normally, I feel it's more or less the mentality to fight for your own students, not to let anyone take away your fame.

In that case, it was completely different. And again, of course, I'm eternally thankful.

Danya: How would you characterize your style as a young boy? Were you incredibly tactical? Did you start exhibiting certain stylistic signs that you still exhibit as a super grandmaster and world championship contender?

Ian: That's a good question. When I was a really small kid, I used to replay a lot of games. I come from a family of teachers, and we had an amazing library. And part of it is we had a lot of chess books. Some really nice books like My System by Aron Nimzowitsch, which is very famous. Also I think a lot of grandmaster tournaments, like from [GM David] Bronstein [ed. note: Zurich 1953] is one of the most celebrated books of all time. There was also some best games of world champions. So I was trying to play, and I think I really never tried to understand what's going on. I just liked the process of playing, of looking.

Besides these, I also liked to set up some ideal positions. So, for example, I play as many moves from, let's say, the white side as I can. And basically I was setting up a3, b4, c5, d5, e5, f5, g4, h3. You know, bishop c4, f4, knight d4, knight e4.

Danya: Ideal structures.

Ian: Ideal structures. Yeah. Sort of modeling the position I'd like to achieve in the real game. And I can't say that's how I learned or understood some chess harmony, but somehow it came from the very beginning. I like nice structure, and everything's protected, everything is connected, everything is coordinated.

So I spent quite some time doing this. Maybe this early love for chess harmony, I believe it's still with me. Yeah. That's something I'm still trying—probably unsuccessfully (laughing)—still trying to achieve in my games.

But also I would say that speaking of more modern times, you should always adapt your style, you should adapt your openings sometimes. Some people start, and their first opening is some classical opening, let's say.

They start by learning the Sicilian or Queen's Gambit or Ruy Lopez. But as for me. I think my first opening was the Caro-Kann because I was basically following the openings which my first coach showed me, and then I suddenly turned into a Scandinavian player.

Danya: Wow.

Ian: Yeah. Also, I had my own research in the Alekhine. It was some good time, and all these openings worked quite nicely in some children championships. I would say, even now, these openings are just not so bad. But probably to score well, you should stick to something more classical, like the Sicilian or Petrov.

First Success and Making Grandmaster

Danya: I know some guy who plays the Petrov pretty successfully at a high level. Won't mention any names. [Ed. note: Danya is talking about Nepo himself.]

When did you start turning heads, raising eyebrows? When did your name start appearing in the newspapers? When did people in your chess community in Russia and at large start to realize that this guy is serious?

Ian: Well, I'm afraid it happened too early because I don't think I could fully digest it back then. I was quite successful as a kid. Despite the success, I could never, until some moment, win a youth Russian championship. I always was sharing first place, and I always was second in the tiebreak. It was very frustrating, I would say. But I think I won something like three times in a row, some European youth championships. Two times it was, I believe, with a round to spare, so the last round I could basically skip.

And also, I think in 2002, it was like a "golden double," both the European and World Youth Championship. Also, Magnus played well, and he shared first place with me. It was one of the few cases when I was successful in the tiebreak.

I think after this, I quickly started playing in some adult tournaments and other age groups like under-18. [Ed. note: Nepomniachtchi was 12 years old in 2002.] I can't say I was fully prepared for this mentally. Of course, that's some sort of a drawback of chess. When a kid goes to chess and plays a lot and plays it professionally early on, without [the] proper mindset [they] could develop a very strong ego.

Danya: Star fever.

Ian: Not necessarily star fever, but like you're responsible for everything. You lose, you win, your move is good, your move is bad. And that's how the ego progresses. And actually, as an advice to parents of young chess players: it should be at least, if not controlled, slightly moderated.

And I think I was quite sure that after all this, that every result should come to me as granted. So my goal was just to make it to the tournament, and there it happened [by] itself, and I didn't really work at chess. Normally when your level increases, you should work more, because the level of your opponent increases as well. But I never worked as much as it was required. Basically, I would say under the age of 25 or 26, I didn't really work too much in chess, compared to my other competitors. So maybe it was sort of a star fever. But at the same time, I think I couldn't quickly get used to the news attention.

Danya: How old were you when you became a grandmaster? Do you remember that exact day, do you remember who you played to get your final norm, or was it sort of "I finally got the title." You were expecting it?

Ian: I would say, unlike many current prodigies and many of my contemporaries, I never—maybe it was also the mindset that you should just learn to play chess, you should learn to play well, you should improve, and so on. And you can make it slowly, but it's the main goal. If you improve, then the results will follow. So this was somehow the mindset. Maybe that's why I wasn't trying to set some firm goals. Of course, I was very frustrated as to why I suddenly stopped winning tournaments. But it took some time for me to connect A and B and say it's really happening.

But speaking of the grandmaster norm, we all know [GM Sergey] Karjakin, who made it more or less in a forceful way, going for some round robins to complete his norm. Basically that's what's happening right now.

But I guess I only played in the round-robin with a GM norm maybe once, and I think I made something like 50%. So it wasn't necessarily to complete the norm but to practice. And I believe I was like 16 or 17 years old [when I became a grandmaster]—so nowadays, an old, wise man [both laughing]. Everyone thinks you won’t achieve much in chess if you're not earning master by the age of, whatever, 14.

I only played in the round-robin with a GM norm maybe once... I believe I was like 16 or 17 years old—so nowadays, an old, wise man.

Danya: Do you think—jumping to a different topic for one question—do you think that's a ridiculous idea? I feel like there are a lot of murmurs in the chess world now that you have to do this by this age. You know, when you are 35, there's no more hope for you. That's been proven wrong, it seems, by [GM] Vishy [Anand], by other players. How important do you think it is to do things at an incredibly young age? Do you think there's any reason to believe that idea?

Ian: Well, the idea is everyone wants to break records. That’s, I think, the main idea, and that's how you get the attention. That's how you get the invitations. That's how you get sponsorship and so on.

But at the same time, I would say that the main benefit of a young age is completely another level of efficiency when you consume information. That's, I think, more or less a known fact. So if some kid is raised in a bilingual family, he'll probably easily learn both languages. I know some of my friends [are] trying to hire some tutors just to teach more languages until [their child] turns seven or eight.

That doesn’t necessarily apply to chess as well, but from my own experience, I might say that learning something new at the age, let's say, of 13, 14, 15 is so much easier than doing the same when you're 25 or 30.

I think that's what really matters. So if you work a lot at that age, this really saves you a lot of time in the future.

And speaking on the titles, I think acquiring a title that early is really a big advantage to other competitors. If you have this 2450 at chess, maybe FIDE master, maybe international master, so not going for some titles early, compared to someone who has 2490 or 2500 and already the GM title. Who will play against some stronger opposition? Who would be invited to round-robin tournaments to test [their] level against real players?

The answer is obvious. And that's why I think it's really important to control these things because it's getting some major advantage in early stages. I can’t say that's fair for the people who are not ready to go for these early norms, not going to get it forcefully.

Progress to 2700

Danya: You crossed 2700 in July of 2010 if my research is correct. If you recall yourself as a person, as a player back in 2010, how has your approach to chess changed, matured over the years, and do you remember what you were first like when you crossed 2700? What was that feeling? Did you start sensing, Hey, wait a second, You know, I'm on top of Chess Olympics now. I've got a serious shot at this. How has your perspective on the game changed in that time?

Ian: I would say about my own chess progress. For two years, one year at least, it always was a long and a little bit sad to play at all. For example, I was really excited when I got my GM norm—I mean, finally, at last, I got a 2600 rating. Some people would say there's more to come. But then the next major progress came to me after quite a while. I think I was like sitting on this 2600 for three years or something. And then suddenly, at some point, I started winning all my games.

Danya: Something changed specifically?

Ian: I can’t say. It was just something. A switch turned, or something. Maybe at some point, you get frustrated about not winning, and [the] last drop comes, and you change your attitude without actually noticing it to yourself.

I can recall I was more or less about 2600, 2620, 2610, 2640, 2620, and then at some point within half a year, I got maybe like 60 or 70 or 80 points. I think it was the Russian Cup, where I scored something like 8.5/10.

And then, it was some open tournament, and it was one of my best tournaments result-wise, the European Individual Championship in Croatia. Since that moment, I [have loved] Croatia so much (laughs). Scored something like 9/11, and it was quite something. I didn't really expect this to happen.

I can’t say I did something spectacular. I did my job, and suddenly everything came together.

Chess Engines

Danya: Let's get to your perspective on chess now, starting with the question of computers. When do you remember starting to use engines very actively in your training and your preparation? And what is your take on the involvement of chess computers in high-level preparation now?

Ian: Well, as far as I remember, I first saw a real computer when I was like eight years old. We came to our friends who lived in Moscow. And I think it was more about Prince of Persia. (Both laugh.) It wasn't anything about chess. But after quite some time, they left Moscow, and they left some stuff to us, as well as [the] computer for the kid. Later on, our friend installed, I think it was a 386 [ed. note: a computer processing chip] or something. So some really, really old stuff, but after we installed Windows 3.1 or something, it was quite nice. Luckily for me also some quite simple computer games—and it was, of course, my main interest.

But also I think we got something like ChessBase free and we had some very, very basic database with some older games of until, let's say 1995, so with some new games. And of course Fritz, maybe it was Fritz Free, maybe it was 5.32. But already, it was like depth seven, depth eight.

Danya: People hearing this now, some of them won’t even know what Fritz is. Crazy thought.

Ian: Maybe we don’t even know about the Fat Fritz. But yeah, it was quite something. Probably I was more interested in, I think, also PlayerBase with some pictures. So I was more interested in looking at the players.

Danya: Like, what did [GM] Garry [Kasparov] look like when he was 15?

Ian: Yeah, exactly. Since then, I had my own small, very small notes, so maybe I was checking something over the board, and I went to the PC, and I was checking what it was going to say. But I assume this Fritz wasn't too skilled.

Danya: So you started using Fritz in your preparation. Of course, fast forward to now, chess has changed so completely. What are your thoughts on that? What were you thinking as chess was changing so rapidly, engines were becoming more and more involved in all elements of preparation and training?

Ian: Well, continuing, yeah. So I think until I turned 12 and won some youth tournaments, I had no laptop, so clearly, whenever I went to a tournament, [there] was no preparation. There was a tradition—maybe in Wijk aan Zee it remains actually— that you are given some printed games of the past round. So this was the main source of information about my opponents. And sure, notes from a database. Normally when you play under 10, it's difficult to find too much info about someone you are paired with. So I think it was in some youth championships, it was our head of delegation who had a laptop, and it was a long queue of players who were coming to him and getting 10 minutes of glory of using the computer. It was quite priceless back then.

But for real preparation for analysis, it started maybe when I was 12 or 13 or 14 because it's not really enough just to have the laptop, you should also know how to use it. The first time I used a database, it was a really big upgrade that you wouldn't collect all these sheets of paper, you can just press a couple of buttons and check the database, and you know what your opponent is playing. It was a huge relief.

Speaking of later years, I started working on my own theory. And of course, I was quite excited about it, and I was very happy every time this line was going to actually arise onto the board.

Some coaches showed me some lines, but it doesn't matter. I think I started playing online maybe when I was 14 or something, and it was quite a limited experience because it was hard to afford internet back then. I was, of course, trying everything online, and I think it's just the same as a lot of players do right now.

So I wouldn't say I'm someone who could call himself a child of the computer era. I think maybe I still belong to let's say, more or less this mix of generations who started actually playing chess without computers, but later on, after achieving some level already, you can’t really think of playing chess without checking lines. Actually, right now, you can just check lines with your iPhone. So that's probably enough to find the moment when you blundered. But for me, it was mostly about checking the database and learning some games, and getting some info about the openings, especially for the first time.

And of course, like now, it's—I don't know. Maybe most of the players are just trying to play like computers already because it’s by far the most effective way. And whenever you just see the computer lines, whenever you see evaluations—I don't know about everyone, but as for me—I'm trying to understand why is that? So that's why you try to dig in deeper into the lines. You're not necessarily learning the evaluation, but you want to see the typical maneuvers and so on. Because normally, before, you would replay some games of great players and see how do they play; how do they manage this or that piece. But now you just do the same with the first line of the engine or the second line.

Rapid & Blitz vs. Classical

Danya: The crazy thing that I've observed is that a lot of these young players, they're not necessarily all that good at blitz. And you can correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems that the heavy use of computers has made them pursue the truth in a position over intuition. So do you think that young players are becoming less intuitive? And related to that, would you call yourself an intuitive player? Do you think the fact that you grew up in a “pre-computer era” has made your style markedly different from the style of young players who are coming up today?

Ian: I believe the style comes from your inner algorithm of thinking. Basically, chess is quite a simple game. So you think, "What if I play this move? What does my opponent do then?" In some way, it looks like coding to me, like there’s some operation: if-then, if-then, if-then. That’s more or less how I try to play over the board.

But at the same time, I hugely rely on my intuition or my common sense. I would say like nine out of ten times at least. So when I see a position, I have some first impression, like, three moves I’d surely consider in this position. I’d say out of these three, most likely one of these three would maybe not be the best one, but surely not the worst one. Of course, it doesn't work just like this, there’s pure calculation where you should just sit and work for half an hour or two to make sure you’re not blundering something badly. That's how, more or less, my head works. I can’t say it's intuition alone, but I can’t say the same about the young players because, you know, shame on me, but I didn't dig deep into their chess character. But perhaps you're right.

I hugely rely on my intuition or my common sense. I would say like nine out of ten times at least.

And I’d say also when we spoke, back then, like, 10 years ago, about some Chinese players, it was a general opinion that, “Okay, all these Chinese players, they only know how to calculate lines. They don't want to evaluate the position." It was more about the technical part of the game—less intuition, more calculation. In these terms, I would say I'm quite the opposite: More intuition, less calculation.

Danya: Do you think that's made you the beast of the blitz player and rapid player that you are?

Ian: Maybe. I were. Because, as I said, I had to adjust my style. Especially right after the opening, you have to solve some very, very direct aspect, or very direct questions. Very concrete problems. That's how you try to trick your opponent in the opening. It's a common opinion that intuitive players, their chess level is not going too low when the time is going too low. Maybe that's one of the reasons. Also, when they speak about the Soviet champs, everyone praises Tal. He was such a great blitz player, completely intuitive. But I would say Petrosian was supposed to be even better because he was very positional. He was maybe also intuitive in some way, but he was more about prophylaxis, and accurate, and also trying to establish connections between the pieces. Like we say in Russia, if everything is protected, you won’t blunder anything. That's probably how it works regarding blitz and rapid.

Danya: You're playing in the Chess.com Global Championship. That's a rapid tournament. One more question on rapid versus classical, I guess two questions. Does your preparation for a rapid tournament markedly differ from your preparation for a classical tournament in your mind? Is a rapid tournament somehow more casual? Does your opening preparation change, or is it a similar type of preparation and mindset going into a rapid event?

Ian: That's a good question because I would say that two years ago, my mindset was completely different. I wouldn't say, “okay, all these internet games are only for fun." Of course, somewhere you can win some prizes. But you can’t really compare it with the importance of OTB or some classical. Actually, I think this equally applies also to OTB rapid and blitz. Of course, you can experiment with openings that have a bad reputation. I'm more or less successful, even now, with the King’s Gambit in rapid and blitz. I even considered playing it in classical once or twice.

Danya: Chess fans would’ve loved that.

Ian: Chess fans would, but what about me, right? (smiles)

Danya: Yeah, that's less important, right? (laughs)

Ian: That's another question. It was like, here is a repertoire basically for classical, here's a repertoire for rapid and blitz. But when I started noticing that, first of all, a lot of strong players started to compete online. Basically, when we had an alternative of playing anywhere apart from online tournaments, it was quite understandable. But when all these strong players started to use some really good ideas, which otherwise would probably be kept until an important game, I changed my opinion, and I'm not as greedy as I was before. If I see a game that’s more or less important, even though it's online, I still prepare, and I'm not trying to save something until a really important game comes.

Of course, this doesn't apply to all the ideas, to all the concepts. But I believe, in that sense, people became less greedy. Also, there is a chance that someone else will play it because, basically, everyone uses the same engines. Everyone uses Stockfish, everyone uses Leela, everyone uses Dragon. Of course, you can just sit and wait and then see some genius playing the same line in a Titled Tuesday. You would never do this, but basically, sometimes you have no choice left, so why would you sit and wait until you have a chance when someone can use this chance instead of you. The number of games got higher because normally, you could see one, or two, or three games of each elite player playing against Magnus. But now they are playing at least 10 to 15 games in some tournaments, at least online. And this surely affects the whole theory status.

Basically everyone uses the same engines... so why would you sit and wait until you have a chance [to play a prepared opening] when someone can use this chance instead of you?

Danya: And then they play seven times in Titled Tuesday and play six other variations. So the output has to be much greater. Obviously, as you're indicating, rapid chess is taken a lot more seriously. Blitz is taken a lot more seriously. There's more money in it. Do you think these people who say that classical chess should either be abolished or it in some way doesn't represent some sort of objective truth? Chess should move toward a more rapid time control from both the perspective of chess as an art in terms of pursuing maximum beauty and from the spectator perspective of making chess palatable and accessible. What is your take on the relationship between rapid and classical right now, and where do you see that going in the next years?

Ian: Well, you can't deny that more people will go to the new Marvel comic movie instead of the opera. That's just a fact. That's our time, that's how it goes. I think it's more or less the same for chess. Classical chess is far more deep. It's the game where you can try to come up with your own concept during the game. It's not necessarily the competition between two teams of seconds who prepare something, you can also come up with your own concept. This happens not quite often, but let's say, out of my own experience, I played against [GM] Anish Giri in 2020 at the Candidates, and he came up with a very nice opening idea, probably a novelty, which I was completely unfamiliar with. But at the time, I played not the best concrete moves, but I had my own idea of what I was going to do, and it worked out. I equalized, and later he even blundered something, and I could even win this game. Normally you can't imagine someone having just enough time to do the same in rapid chess. It's more about your first impression, more about your general feeling.

Classical chess is far more deep [than rapid]. It's... where you can try to come up with your own concept during the game.

Maybe it's even better for me, I don't know. (smiles) I get back to this full-time intuition routine, not taking everything so seriously, just “okay, this move looks good, let's go for it.” Of course, it would change the situation in the ratings list. We have separated ratings lists for classical, blitz, and rapid. At the same time, it's the same pieces, same board, 64 squares, but it's a little bit of a different game. Personally, when I was like 15 years old, I liked blitz. I didn't understand why I would play rapid at all. Why not just play blitz?

Danya: Why that middle ground?

Ian: Yeah. Over time it's not me becoming older, but I think it's about understanding that classical chess has its own beauty. Of course, it's more entertaining to watch 3+0 and flagging each other. I think I used to be quite good at this as well back then, maybe I can get back some of my e-sports skills (laughts).

Danya: Your priorities have shifted.

Ian: Yeah, absolutely. In terms of enjoyment for me. I really find a good classical game, in which you're not necessarily winning, but you have like a big clash. You spend a few hours thinking about something really interesting, and you try to get into your opponent's head: What is he thinking? What is he planning? When everything just happens in three minutes, you have the result, that's quite favorable for our time overall. But I think it leaves most of the beauty behind the scenes.

Chess Commentary

Danya: And you think there is a way of commentary being done right, of conveying the beauty of classical chess to the public at large. That's a doable task, in your opinion?

Ian: I don't know. I used to like the Mr. Bean series. In one of the episodes, which is probably called "Goodnight Mr. Bean."

As it's obvious from the title, he's trying to fall asleep. He switches on some TV channels, and there is some chess match on TV. And it's someone moving very slowly, in complete silence, only the clock is ticking. (Mimicking the scene, Ian motions as if making a chess move, then pulls hand back.) This almost works for him. And then, of course, suddenly some ads [come in] and (Ian motions as if suddenly waking up).

It shouldn't be shown as some entertaining thing. I can’t say you should be dead serious. It's interesting to maybe [show the players’] blood pressure, pulse, and so on. Maybe you should add something to entertain the audience. But at the same time, if you are not doing this at the opera, why would you do this with classical chess?

It’s a very big task, maybe for us, maybe for upcoming generations, to find the balance. I can imagine it’s really hard for, let's say, a newcomer. When you see a football match, there are 45 minutes, then a break, then 45 minutes, maybe some penalties, and you know the result. You don't spend your whole day. Our longest game in Dubai was like eight hours. Game six.

I think it was a little bit too much for the players and probably a little bit too much for some random people who just wanted to watch chess for the first time. Of course, someone likes it, but I think [most people] think, “Okay, it's a little bit too long.”

I think [Game 6 of the 2021 World Championship] was a little bit too much for the players and probably a little bit too much for some random people who just wanted to watch chess for the first time.

There is also a good example in the National Hockey League. Back in the beginning of the 20th century, I think it was actually two periods for 30 minutes. And then they found out that they get all the money not from tickets but from buying something in between—some drinks, some snacks. So they just added more and more breaks. Maybe one day chess will shift to something like snooker, have longer open matches and frames. Some early, morning session, evening session, and so on. So you are getting your result quicker. Maybe that's a major problem [in chess], that sometimes [you need] four, five, six hours to get the result. Maybe that’s a problem. I don't know. The [depth] of this discussion is just impossible to cover.

Candidates Tournament 2020

Danya: Yeah, it's a vast topic for sure. Another vast topic that I want to switch to is the world championship. You win the Candidates for the first time. You realize after the last game, you're going to face Magnus Carlsen in Dubai. Can you walk us through what that feeling was like going into the 2020 Candidates? Did you motivate yourself with the idea that you could be facing Magnus? What was your mindset like at the time?

Ian: Oh, well, the moment I qualified, I think [I had] a very practical approach. I told myself, “All right, you played, let's say, a thousand classical games or something over your career. Some of them you played well, some of them you played not so brilliantly, but for now it's basically 28 games until you get the title and, probably, you should try harder because inside these 28 games, you should really take it seriously. Prepare, be a sportsman, don't waste time for something else. Less games, less entertainment, just more work. Because you've played so many games before, so why not do it?”

Nepo be like:

— Rakesh Kulkarni (@itherocky) April 26, 2021

Hey Ma! I made it! #FIDECandidates pic.twitter.com/4A5vhvwrw6

I can't say if this mindset worked, but actually, it was my mindset. I just try to take more or less every game as an opportunity to train myself, to become better. But speaking of regular round-robin tournaments or especially some blitz and rapid, I can't say it’s a matter of life and death for me. There are more principled opponents, more important games, so they never lead me to some fanaticism, or something. It’s never a religion.

When we speak about the World Championship cycle. I'm quite realistic that when, let's say, I play the World Cup, it's more or less a lottery. In the lottery, you have the initial chance of one out of 128. When I'm getting eliminated from the World Cup, I probably take it quite commonly. But when it’s obvious that you can [make it]... There are like three tournaments, like the Grand Prix, so you can make it to the Candidates. Well, you should just be consistent, you should be stable, you should play well all the time. And that's probably on my mindset. Maybe it helped me in two or three stages back in 2019. Now it's like one last step. Basically, 28 games is nothing in terms of your whole career. You played hundreds of games to get to this place, and now it's a such a small step to be made. But yeah, I think it was quite naive (laughs).

Danya: As you were preparing for Magnus, could you let us in on what percentage of time was spent on opening preparation purely versus general preparation in terms of getting yourself to peak form?

Ian: Hmm. Well, I would say, first of all... This was the year between the first and second leg of the Candidates. I think it really helped me chess-wise because seeing the goal so close in front of your eyes, it motivates you to work more. I think starting with the SARS pandemic, I really worked as never before. Normally I have some routine. Then I have some training sessions, then I work, then I have tournaments, and then I work. When I have nothing, then I just chill here. Maybe I play some blitz online, maybe I can check one or two opening lines, but it's never something... I mean, it was never like a real schedule.

Seeing the goal so close in front of your eyes, it motivates you to work more.

But in 2020, after the tournaments stopped, I think things changed completely. And before this awful year… I mean, it’s a very, very short period in terms of preparing for a world championship match, especially in my case, since I started working on chess quite recently. I have changed my life completely, and I think that maybe it was a little bit too much. It's always better to keep some energy, but I felt like I should do so many things—to change my style, change my openings, change my schedule, change my diet or whatever, change everything! So basically, I changed my whole life, and it was quite stressful, especially when you do it almost all of a sudden. I couldn't imagine that the effect could be not only positive but also inflict some damage.

World Championship 2021

Danya: All right. So you're sitting in front of Magnus game one of the Dubai 2021 World Championship. What's going through your head at that moment? Is it anxiety? Do you shut everything out and treat it just like a regular game? Can you walk us through your emotions as the world championship match began?

Ian: Well, it's like coming to take an exam when you are absolutely sure you're not prepared. You started so poorly, and you surely want to make it through. You surely want to get to mate.

Somehow I always had no feelings of chess superiority from Magnus. I mean, I was quite optimistic about the match. I would even say that probably the first half of the match was more or less proving my view. But, at the same time, I probably underestimated how the other side was dealing with the match. So it was not the ‘tournament edition’ of Magnus. It's not completely another player, but surely he adapted his strategy and caught up to everything.

But back before the first game… Of course, I'm always optimistic entering any event, and until some moment in Dubai, I was also quite optimistic. But yeah, not for all the match. It's not something completely new, I'm more or less used to this: Photographers, cameras, press, and some excitement, hype, and so on. But it was a little bit of a new experience.

I mean, playing in matches is a little bit different than playing in tournaments. Playing in tournaments, you can come and talk with someone, some other player. You can change the subject of your attention. You can take a look at other games. For example, on the team championship, you can look at games of one of your teammates or other competitors.

But here you are only with your game and your opponent, and this was sort of a new feeling. I think the previous match I played was against [GM] Dmitry Andreikin in 2012, but it was quite short, I think four games, maybe six games. It was some experience, but, of course, this special type of experience you can only get by basically playing the match. Also, I spoke to quite a lot of people who played matches, who won the match, who lost the match. And everyone has something to say, they can point out their own mistakes. And maybe my idea that all these experience could be useful was a little bit naive because, in fact, every game, every player, every game, every match is quite unique. Trying to fill myself in someone's shoes... maybe it was worth it, but now I think that I shouldn't have relied on this too much.

Danya: All top chess players have a vast team of assistants, coaches, seconds, friends, and before a World Championship match, I would imagine that you assembled and put into force a team of such people. Could you let us in on some of the most important players on your team? And would you say that during the match, did they mostly play the role of assistants on the board, or did they mostly play the role of friends who were supporting you after difficult games?

Ian: Well, I would say that you don't want to change the lineup which was successful. And I more or less tried to keep everyone who was on the [team] for the Candidates. So I would say that most of the team remained the same. [GM] Nikita Vitiugov, back then, he said he would like to focus on his own career. So maybe helping was a little bit too stressful. Anyway, he had his reasons to skip the match, so he was replaced by [GM] Evgeny Tomashevsky, someone who I think helped [GM Boris] Gelfand during his match against Vishy.

You don't want to change the lineup which was successful. And I more or less tried to keep everyone who was on the [team] for the Candidates.

Danya: The Professor.

Ian: Yeah, The Professor. I mean, he's the true professor, in life and in chess—a very nice person. It was a nice combination of basically everyone who was with me on the team was not only a great chess player, analyst, and second, but also my close friend. For example, Evgeny, we have known each other, I think, since 2001 or something.

So this was more or less set, and of course, I had a lot of talks with great Russian champions of various years, not only general advice but also chess advice. And also, there was a huge role played by [GM] Peter Leko, who almost, alas, almost is not enough, but almost won his match against [GM] Vladimir Kramnik. Probably, in some way, I think helping someone winning the match is always like a redemption in that case.

I would say that I had never had so many trainers, so many coaches, so many seconds. And since the Candidates, this has changed for me and, of course, it was quite useful for my chess progress because, once again, I would say compared to most of the top players, I started working on a regular basis when I turned 26 or 27, so it was very late. I mean, I was for quite some time in the chess elite, like 2700 plus. But at the same time, it was obviously not enough to compete for the title. That's why I'm quite optimistic about what's going to be the future because I think I have quite some room to improve.

Danya: Well, you showed that because you won the Candidates the second time in a row, a dominant performance. Would you say that your match with Magnus impacted your performance? Were there any specific lessons that you took away from the Magnus match that you applied in the Candidates and that you will apply in your upcoming World Championship match against Ding Liren? And I'll get to the question of Magnus abdicating his title in a moment.

Ian: Just one second. It's good to mention Potkin also.

Danya: M-hm. [GM] Vladimir Potkin.

Ian: Yeah. More or less the Head Coach, the coordinator back then, basically for most of the time, like 15 years, I think. My close friend, actually, and also my coach for most of these year, was Vladimir Potkin, who made it this long with me and probably for pretty much most of these years. Ok, he was involved in other projects, but at the same time, he was more or less my only assistant throughout this time.

World Championship 2023

Danya: So you had a match with Magnus, then you came back, you won the Candidates again, and now you're facing Ding Liren for your second chance at a world title. I'll get to the question of Magnus abdicating his title in a moment. First, let's start with your approach to this upcoming world championship. Would you say that there were specific lessons that you learned in your match with Magnus that you will be applying in this world championship and that you applied in the Candidates, or are you over that match? Are you trying to think about it more or think about it less going into this match?

Ian: Well, every unsuccessful game is a lesson. And of course, the main thing I took away from this match was my experience, and the experience was quite sad (smiles). But maybe that's why it was quite useful. Even in the middle of the match, even until I started blundering everything in one move, I came to the conclusion that it was pretty much different from what I had expected.

Every unsuccessful game is a lesson... The main thing I took away from [my match with Magnus] was my experience, and the experience was quite sad. But maybe that's why it was quite useful.

Now, in a way, I can model the match, how it goes, how it might go. For example, my general idea was, to win the Candidates, I should win like three or four games. To win the match I should win one game and lose zero. I mean, it's also quite a childish approach, I think.

Speaking of the upcoming match, I wouldn't say it's my only advantage compared to Ding, but it's one of the very important things. I have a more or less bitter experience, but nevertheless, it's an experience. I'm not sure if he's much used to this type of chess. Of course, he's playing some matches here and there, but they're like four games, six games. It's not quite the same. It's not the same level of excitement, involvement, and preparation. So probably, this will favor me.

Danya: Your preparation for the match with Ding, would that preparation have been different if you had been facing Magnus Carlsen, or is your routine largely going to stay the same?

Ian: Well… That's an interesting question, by the way, because, of course, when you prepare for a match, first of all, you prepare for the person you play with. This is also quite an important thing, which I underestimated previously because I would say Magnus changed his style, especially for the match, quite a bit. I’d say he’s normally more opportunistic whenever he plays, but against me, he was very, very strict about giving extra chances, he was following his general strategy, and so on. I think he was just trying to play well, especially after maybe his first game with White, when he was close to losing, and he started to play very accurately and to just let me make my mistakes myself instead of provoking for something, for example.

Let's see how Ding also plays. Will it be like the usual Ding we’re all used to? Very active, fighting for the initiative with both colors? Very principled? Or will it be some other kind, some other 'special match edition?' Returning to my preparation, I think that I was mostly focused on my own. I should play well, and what happens, happens.

Obviously, it's hard to spot weak spots in Magnus’ play, in his style, but that's probably also something I should have been focused on as well as preparing my own. Maybe playing some specific lines. What I did in the match was more or less trying to win in his territory. If you want to play some boring, calm chess, I'm up to it completely. I'm even more interested in these. Result-wise, maybe the match could’ve gone differently. But maybe it wasn’t the finest idea.

Again, speaking of Ding Liren, he also has his strong sides and probably not so strong, so I will take into much bigger consideration his person, his style. Overall, him as a chess player and as a person rather than what it looks like I didn’t do for Dubai.

Conclusion

Danya: Are there days when you wake up and say "Man, this stuff is incredibly hard. I just don't want to do chess today"? What is it that keeps you going, that keeps you working as hard as you're working in preparation for this next very important trial in your chess career?

Ian: Probably when you wake up and think like this, maybe it's a good idea to have a rest. That's probably something I never let myself, and I never let an extra rest day happen before the match with Magnus. This also was quite a questionable approach because, even in the last two or three weeks in Dubai, when I was supposed to go to the beach and swim, drink cocktails, and so on to gather some extra energy and recharge my battery, I was mostly sitting with the laptop and polishing some lines. Even statistically, you use two to three percent of your preparation during the match. The rest comes when someone plays it instead of you or something happens, like in the next year. That’s normal.

Even statistically, you use two to three percent of your preparation during the match. The rest comes when someone plays it instead of you.

Back then, I felt it was completely and incredibly important to have everything polished to shine. And that's why I never stopped any chess work until like two or three days before the first game, which was quite wrong. Probably this is also one of the lessons: If you somehow think that it’s better to rest, you should be realistic and understand that you cannot repeat or memorize all the lines in chess.

Of course, you should be candid with yourself and tell yourself that you just have this amount of work you have to do, and once you're able to do it, you can do some extra, but you should also not forget that it’s actually still a game and everything is decided not at home, not in front of your laptop, but when you come to the board. And if you basically can't function properly and your brain refuses to work, like it happened in December, maybe it’s not such a brilliant strategy to work too much.

Danya: Final question. What do you find most beautiful about chess? Is there a particular thing that carries you forward that makes you try to be the best chess player that you can be? Do you consider yourself an artist, or is this an athletic endeavor for you? How would you characterize yourself in your pursuit of chess excellence? And what do you find most appetizing, most beautiful about the game that we all love?

Ian: Well, I don't really like to speak about myself. I'd say somewhere in between. I would happily be, let's say, an artist and play only for beauty, prizes, and so on. Just for the entertainment of myself and the audience. But the reality is such that if you want to win, you should be way more pragmatic than you want to be. I made some new additions to my playing style, which probably helped me a little bit with my results in the tournaments. When I am playing in a tournament, let’s say Rapid and Blitz or some very strong round-robin, and I see a nice idea, then okay, why not go for it? When you play only for the result, it's a different approach.

So, sadly, I'm a little bit envious of the chess amateurs who can play for pure enjoyment, for themselves. This is, first of all, a game. For me, of course, tonight, when we speak about achieving some goals, it's pretty much about the sport.

Danya: Thank you so much for your insights, your stories, and your time. This was awesome. Good luck in the rest of the Sinquefield Cup.

Ian: Thank you!