How To Study Openings The Right Way

The opening is the part of chess that players study the most. I doubt that this statement came as a big surprise to you, considering the humongous amount of books and videos on this subject. When I ask my students what kind of chess books they have, as a rule, most of them are opening manuals.

Unfortunately, most chess players don't know how to study openings, so they just try to mechanically memorize the content of the books and videos mentioned above. Therefore, the questions posted by our readers in the comment section of my last article are quite instructive.

Here is one of them: "[...] there was one part I found to be misleading. At one point, the move 1. c4? was given a question mark, which I do not understand. The English Opening is a perfectly respectable opening. Perhaps the meaning was that the subsequent line is dubious?"

Even though I specifically provided a link to my article, where a very detailed explanation was given, I nevertheless copied the most important part of it: "Before anything else, you need to learn the classical principles of the openings (center, development, king safety, etc.)." But I guess I need to spell out the reason why I gave the move 1.c4 a question mark in that context.

First of all, as you can see, all the games in the article, except just one, started with 1.c4. Two of them were true strategical masterpieces, and in another one GM Nodirbek Abdusattorov beat GM Magnus Carlsen, which is a great endorsement for the English Opening. But in the game where I gave it a question mark, the person who played White was a nine-year-old kid rated 1543 and in my opinion, the English Opening is not the best way to start a game at this age and playing level.

In order to demonstrate this point, let me share my personal journey in the English, which started with 1.c4? and a question mark, but ended with 1.c4! and an exclamation mark.

In October of 1980, one of the strongest Soviet tournaments, the first league of the national championship, took place in my home city of Tashkent. This tournament gave an enormous boost to chess life in Uzbekistan. Way before the Internet, the sheer ability to see a real grandmaster was priceless. Even better, these grandmasters were giving a lot of simuls.

One day GM Vladimir Tukmakov, one of the best Soviet players at that time, was giving a clock simul to the top junior players. I was one of the few lucky kids who managed to make a draw. A couple of days later, Tukmakov was giving a second simul against the same opponents. Before the simul, he announced that we should switch colors (in other words, those of us who played White should play Black now.) And here I had a problem. You see, I drew the first game with the black pieces, and I wanted to play Black again since, at that time, I preferred to play with the black pieces. Don't be surprised, there are even very strong players who prefer playing Black.

I will never forget my conversation with the late GM Evgeny Sveshnikov, the originator of the Sveshnikov Sicilian. He was a truly unique person on many levels and deserves a multiple-volume book about his chess heritage. Sveshnikov was one of those chess players who preferred to play Black. So when we played in one tournament, he said that he was going to beat his next opponent, who was quite a strong player. I asked him why he was so sure. I will always remember the beginning of his lengthy answer: "Well, first of all, I am playing Black..."

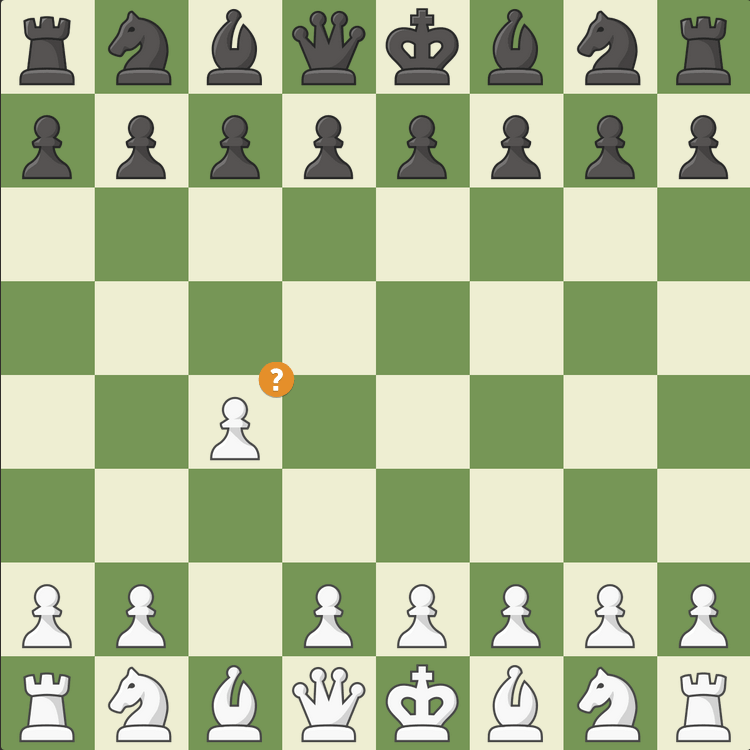

Anyway, back to my story. When GM Tukmakov announced that we were supposed to switch colors, I tried to pretend that I didn't hear the announcement and set up the black pieces for myself. When Tukmakov came to my board, he apparently remembered quite well the little kid who drew him a couple of days ago. He just said that the last time we played, I was Black, so now I have to be White. I didn't have a choice, so I turned the board, and played 1.c4?

Generally speaking, I always started my games with 1.e4!, but here, with an unexpected change of plans (I was preparing to play Black!), I panicked and played the English. I lost the game quite miserably: My much stronger opponent just completely outplayed me positionally and I didn't even understand where I went wrong. After the game, my coach explained to me that I had pretty much wasted an opportunity against such a great player.

Had I played my usual 1.e4, I would most probably have lost anyway, but I would have learned much more from the ensuing sharp play than from that boring 1.c4? game. By the way, I was 11 years old, so not much older than that kid whose game I used for my article.

Now fast forward eight years. I was already an international master and it occurred to me that because I played the Sicilian Defense my whole life, why not try the English Opening, which is essentially an attempt to play the Sicilian with colors reversed? After I switched from 1.e4 to 1.c4, my results improved. Here is the game that brought me my grandmaster title:

So, that was my personal journey from 1.c4? to 1.c4!

Now let me answer another question from the comment section:

"I've been trying 1.c4 with reasonable (questionable) success lately, but feel as if I don't fully understand the theory/purpose behind it. Could you perhaps recommend anything for me to start with? Thanks."

This is a very good question! The problem with most opening books is that they just dump tons of chess variations on you, but at the end you don't quite understand the purpose of these moves, as the reader correctly pointed out.

Let me give you a simple example that shows quite well why you need to know the ideas of your openings. In my game on move nine, I traded my fianchettoed bishop to damage Black's queen's side. In many cases, such a trade makes your own king vulnerable, so why was it so easy for me to part with my bishop? The answer is simple: I knew the following two games played by world champions:

As you can see, in my game I simply copied the idea executed by two world champions since the positions were practically identical. But it is not always that easy. What should you do if you find yourself completely out of book? The knowledge of classical games should help you here as well.

Let's take a look at my move 15.exf3! Why did I deliberately spoil my pawn structure when I had 15.Qxf3, a perfectly fine move? Moreover, I already used this idea before, where my move looked even more shocking:

Here my move 13.exf3! looks even more ridiculous since I could recapture with both queen or bishop without spoiling my pawn structure. Is there any reason for White's madness? Well, there is one main reason: White wants to open the e-file. Also, in some variations, the f3-pawn can be used as a battering ram to damage Black's castle. Again I didn't need to find this neat idea on my own since I knew the following game of another world champion. GM Anatoly Karpov took full advantage of the open e-file, but didn't find the best continuation of his attack at the decisive moment:

I have to admit that I learned this idea from an Alexander Alekhine game before I saw Karpov's game. It's quite possible that Karpov himself learned this idea from Alekhine as well.

Now you can see how difficult it was for GM Boris Alterman to play our game: I had four world champions standing behind me!

So, let's get back to the question of how to study openings. As the first step, I would recommend studying the games where world champions and elite grandmasters play the opening of your interest. That should give you a general idea about typical ways of attack and defense, the best placement of your pieces, key elements of strategy and tactics, etc.

Now let's imagine a situation where you are thinking about employing one of the numerous meme openings in a tournament game and wondering how Jose Capablanca, GM Bobby Fischer, GM Garry Kasparov, or GM Viswanathan Anand played them. So you check a database and get this response:

Well, I guess that's another reason to study classical games. Even this unusual response can teach you something about chess.