Havana '66

Fulgencio Batista, president of Cuba during WWII and again from 1952-1959, backed by the US government as well as by organized crime, enriched himself at the expense of his citizenry. One of his methods of enrichment was to encourage the building of large, luxurious hotels/casinos from which he and his regime received a 20% share in the gambling revenues. On March 18, 1958 Conrad Hilton opened the largest hotel in Latin America, the Havana Hilton. Hilton managed the property but didn't subsidize it. Batista worked out a deal with the Cuban Food Industry Workers Union to borrow the money from their retirement fund as an investment for the Union. Maybe it would have all worked out but for the Revolution. Seeing the writing on the wall, Batista fled Cuba with $300 million dollars on the last day of 1958.

On January 8, 1959, the leaders of the revolution, primarily Fidel and Raúl Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos and Che Guevara, triumphantly entered Havana and set up their headquarters on the upper two floors of the Havana Hilton with Castro making suite 2324 his personal accommodations - a symbolic slap in the face to the foreign interlopers. Although the new regime craved the revenue from the hotel, the growing chasm between Cuba and the U.S. ensured empty rooms. In October of 1960, all Cuban hotels were nationalized and the Havana Hilton was renamed the "Habana Libre."

The Hotel Habana Libre, the site of many significant chess tournaments

The Hotel Habana Libre, the site of many significant chess tournaments

It's said that Ernesto Guevara learned chess as a child from his father who took his 11 year old son with him to the 1939 chess Olympiad. The Olympiad was being held in Buenos Aires not too far from his home. It was there that José Raúl Capablanca caught the child's eye and the island of Cuba first came to his attention. Ernesto , enchanted with chess, became a relatively strong player over the years., After the successful revolution in Cuba Ernesto "Che" Guevara was made Governor of the Central Bank and Minister of Industries, giving him a free hand with the government's money.

Guevara spent lavishly on chess starting with the Capablanca Memorial of 1962, sparing no expense and offering particularly hefty prizes. As with most Cuban chess events of this time, Guevara provided the backing and official support while José Luís Barreras, head of the National Institute of Sports, Physical Education and Recreation, did the actual work. The Torneo Capablanca in Memoriam became an annual affair and put Cuba solidly in the chess world radar. Most famously, Fischer, who was invited to play in 1965 but was prevented from traveling to Cuba by the State Department, played via telex from the Marshall Chess club in NYC at great cost to the Cuban sponsor. During this time Guevara and Barreras were securing, planning and organizing a spectacular event for the following year, the Chess Olympiad. Guevara would leave Cuba before the actual event and would die in Bolivia the year after. Obviously engaging, charming the players who met him, the mythical "Che," emblazoned on t-shirts and counter-culture posters, contrasted sharply with the ruthless "Butcher of La Cabaña" (referring to the political prison he supervised). Whatever the actual facts or one's perspective, whether he should be honored or reviled, there's no doubt that Ernesto Guevara led a remarkable life and is only rivaled by Capablanca himself in putting Cuba on the chess map.

Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Barreras had close ties with the Czech player and FIDE vice-president , Jaroslav Sajtar, an anti-Soviet who was amenable towards staging an Olympiad in Latin America - the only other Latin American venue had been Buenos Aires in 1939, the event that so inspired Ernest Guevara. Che, of course, was ecstatic at the idea of any chess tournament and Castro saw the propaganda advantage in it. The logistics, expense and expertise involved in such an undertaking is mind-boggling but somehow José Luis Barreras, Jaroslav Sajtar and company managed to pull it off.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

The games were played in the Salón de los Embajadores of the Hotel Habana Libre, formerly the casino. The Salón Primavera was set aside for journalists, analyzing, post-mortems and blitz.

Working with $5 million dollars (some say a good bit less) and a pool of 1000 skilled workers to employ, it was still a complex affair. With a record 52 countries involved (oddly West Germany boycotted the event for political reasons while the U.S., Cuba's biggest political enemy, accepted its invitation) and 306 players, the planners divided the teams into 7 groups from which the two top winners would move into the finals.

Most team fielded 6 players (two being reserves) but some could only field 5 while one (Panama in group 6) fielded 4, so the groups were established with these numbers, followed by the winners going to the finals:

group 1 - 8 teams - 47 players - USSR, Spain

group 2 - 7 teams - 42 players - Yugoslavia, Iceland

group 3 - 7 teams - 41 players - USA, Norway

group 4 - 7 teams - 42 players - Argentina, Denmark

group 5 - 7 teams - 40 players - Czech., E. Germany

group 6 - 8 teams - 46 players - Hungary, Cuba

group 7 - 8 teams - 48 players - Romania, Bulgaria

The Olympiad opened on Oct. 23, 1966 with a unique Living Chess display in the form of a ballet using students from the Manuel Fajardo Escuela de Educación Física and the Escuela Nacional de Arte de Cubanacán (who also provided 1000 singing voices accompanied by the Orquesta Sinfonica Nacional de Cuba -Frank Brady, "Profile of a Prodigy") under the professional direction by Alberto Alonso, the famous Cuban ballet Cuban dancer and choreographer at the sports complex, Coliseo de la Ciudad Deportiva which had opened in 1958 just prior to the regime change. It followed one of the 1936 games between Emanuel Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca from the Moscow International (Capablanca won the event, of course).

1st place USSR fielded 6 grandmasters; 2nd place USA fielded 4; 3rd place Hungary, 4; 4th place Yugoslavia, 6; 5th place Argentina, 2 ; and 6th place Czechoslovakia, 4 — 26 of the 38 grandmasters participating were in the top 6 teams. The 14 teams in the Finals held 35 of the 38 GMs and 24 of the 45 total IMs.

Results

Results

As is the case with many events Fischer entered, he became the center-of-attention at the 17th Olympiad starting with a broken promise.

Larry Evans, writing for "Chess Life," Dec. 1966:

On both these occasions the U.S. team was headed by our number one player, 23-year-old Bobby Fischer, the somewhat eccentric glamour boy of international chess; and both times he was mainly responsible for our good showing.

This time he came within an ace of taking the gold medal on board #l, with 15 out of a possible 17 points (14 wins. 2 draws, 1 loss) as against 11½ out of 13 points (10 wins, 3 draws) for world champion Tigran Petrosian. Petrosian's winning average was 88.46 to Fischer's 88.23, a microscopic difference. Fischer faced tougher opposition and played four more games. Had he been willing to accept a draw in his 16th game, when it was offered to him by 21-year-old Florin Gheorghiu of Rumania, he would have had no losses, the same number of draws, and far more wins than Petrosian—for a higher percentage and the gold medal. These details were known to Cuba's numerous and demonstrative chess fans who, right up to the last day, expected that Fischer would win. The thousands who couldn't squeeze into the tournament hall followed the games play-by-play via radio, TV, and an elaborate $80,000 electronic demonstration board that had been set up opposite the Habana Libre (formerly Hilton) hotel. But it was the brilliant and aggressive character of Fischer's play, and his willingness to take on all comers, that gained the affection of the crowd and obviated any hostility or irritation that might have developed as the result of a contretemps that took place on the second day of the finals.

After the tournament was over, some criticism was directed (rightly or wrongly) at our non-playing captain, Donald Byrne, for allowing Bobby to take on more than 15 opponents. His victims read like a who's who of international chess. After his first 15 games he had 13 wins, 2 draws, and the gold medal in his pocket. There is no question that, under the same circumstances, the Russians would have played it safe and removed one of their stars from the lineup. But since we were still engaged in a tight race for second place Bobby was given his head and, in effect, beat himself in his encounter with Gheorghiu. He failed to consult the captain when offered a draw. "Are you playing for a win?" asked Gheorghiu, shortly after the opening. "Of course!" snapped Bobby. None of this was lost on either the Russians or the Cubans, though it was given scant notice in the local press.

A good deal was said, however, in all the Havana papers about Fischer's refusal to play before 6 p.m. on Saturday, November 5th. It has been generally accepted, for the past year or two, that Fischer never plays, or even discusses the game, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday; that period is, he says, his "holy day." He has gotten religion, but no one has been able to find out which, or whether its has a brand name; the subject is one of several that Bobby flatly refuses to discuss.

Still, Lt. Col. Edmund Edmondson, Executive Director of the U.S. Chess Federation, had raised this point when making arrangements with one of the responsible Cuban officials prior to the departure of the U.S. team; and he had been assured that Bobby's Sabbath would be respected. But on Nov. 5, when, by the luck of the draw, the Russians were asked to postpone the start of Fischer's game against Petrosian, from 4 to 6 p.m., Alexi Serov, manager of the Russian team, not only refused but treated U.S. team captain Donald Byrne to a lengthy, irrelevant anti-American harangue.

(At this point, Byrne filled in Col. Edmondson, in New York, by telephone. After consultation between our team members, captain Byrne, and USCF officers (by telephone), the U.S. position was that our team had gone to Havana after being assured that schedule variations would be made to permit Fischer's participation in accordance with his religious beliefs. Anyone refusing to honor this agreement was, therefore, refusing to play the U.S. team, since Fischer was so obviously the team leader in playing strength. Olympiad officials, and the Soviet team, were notified that the U.S. team would be present to start the round at 6 p.m. in accordance with our prior arrangement. Serov, again with irrelevant remarks (this time disparaging Fischer's playing strength), flatly refused to compete and said his team would be present at 4 p.m. When he received word of the Soviet stand, Col. Edmondson met the following cable to Mr. Folke Rogard, president of F.I.D.E. in Stockholm:

USSR REFUSED PLAY USA MATCH UNDER ORGANIZING COMMITTEE AGREEMENT DELAY FISCHER GAME START. YOUR INTERVENTION URGENTLY REQUESTED FOR SOVIET COMPLIANCE, IF THEY CONTINUE REFUSAL WE CLAIM 4-0 FORFEIT.

Back in Havana, the U.S. team arrived at the playing site at 6 p.m. to find that a rather premature action had been taken; the USSR-USA match score had been posted as a 4-0 forfeit in favor of the Soviets, with no one having yet learned the views of F.I.D.E. President Regard. Since everyone else—even the Soviet players—wanted the match to be played, it seemed that their manager had gone off on a tangent contrary to the interests of chess. Upon hearing this news, team captain Byrne reiterated the U.S. position to chess officials on the scene. From New York, Col. Edmondson sent clarifying messages to various parties who would be interested M a fair out, come of the dispute.The next day, F.I.D.E. President Rogard's recommendations reached Havana. He asked first of all that "a friendly agreement be obtained" to reschedule and play the match; stated that if the parties refused an Arbitration Council would have to be set up to reschedule the match; or, if rescheduling were found not possible nor appropriate, the match results could be scored as a 2-2 tie.

"Consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds," and Serov was nothing else if not consistent; he refused to consider the possibility of "friendly agreement.")

Accordingly, on November 9, an Arbitration Council—with members from Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cuba, and Czechoslovakia—taking into account the fact that prior to Nov. 5 every other team had agreed to accommodate Fischer's scruple, urged the Russians to agree to a rescheduling of the match. Igor Bondarevsky, captain of the Russian team, had at this point suddenly replaced Serov as Soviet spokesman. Bondarevsky explained that, since the incident had developed "international repercussions," the decision would have to be made by his home federation. He added that one could be expected in a few days. But the very next day, Jesus Betancourt, director of INDER the Cuban Sports Federation) announced that, in order not to disappoint their Cuban public, the Russians had agreed to have the match rescheduled for Nov. 14, This was instantly hailed by the Havana papers as a "noble gesture," and for the next several days they publicized the coming match. (One cartoon depicted Petrosian and Fischer in baseball garb, warming up in the pitcher's bullpen to compete against one another.)

If it seems like Evans might have possibly been treating Alexei Serov too harshly for effect, in "Chess Without Mercy," Viktor Korchnoi gives a similar treatment from the Soviet perspective. He also included the story of Tal's misfortune at Los Violines night club (I used Google Translator, so some phraseology may look awkward).

The competition is held under the auspices of the Government of Cuba, with its full and, of course, financial support. The USSR team lives in an excellent hotel "Havana Libre", in the past "Havana Hilton", the team has an excellent interpreter - one of Fidel Castro's personal Russian. True, just before the games began an emergency happened. Tal and I at night - of course, without the knowledge and permission of our superiors - decided to take a walk. We went in together with the Cuban acquaintances to the night club; And here, at a time when Tal was dancing with a young Cuban woman, he was hit on the head with a bottle! Bloodied Tal and me were brought to the hospital [the Calixto Garcia Hospital], an interpreter arrived there in the morning. The wound over the eye was washed and stitches were applied. All those who were at the bar - 43 people - were sent to the Cuban Security Committee. One young man confessed that he had struck a blow from jealousy. And the hotel in the morning - a meeting of the team. Tal got his [punishment] for disobedience - a mighty blow, as you, the reader may understand. And I was criticized for weakening the team on the eve of the decisive encounter: the evening match with Monaco ...

Tal went on the game in the fourth round. Still unhealthy, wearing sunglasses, he showed absolutely the best result of the Olympics - 9.5 out of 11. But neither the grudging KGB never forgave Tal or myself ...

Chess events at the Olympics were no less exciting than our private lives. The US Department at the time weakened the cultural blockade of Cuba. The US team led by Fischer arrived in Havana. In those years, Fischer did not play on Fridays and Saturdays, and the organizers of the Olympics, high government officials promised him that his demands for transferring important parties to other times would be met. The decisive duel between the USSR and the United States was approaching. It fell to play on Saturday. The Americans asked to postpone the start of Fischer's game for several hours so that he could take part in the match. Our team met for an emergency meeting. The head of the team was Alexei Serov, an employee of the CPSU apparatus. Since he was with chess players for the first time, he had little idea of chess affairs. His assistant and chief adviser was the team's coach I. Bondarevsky. A man of a harsh nature, he firmly applied the principle of the Hammer and Vyshin school in negotiations with foreigners: "Since we, that is, the Soviet Union, are stronger than anyone else in the world, we do not accept any conditions - we impose them!" It had already happened under his direction in Delegations, he had to challenge his point of view and even win in the dispute. I asserted: "Since we surpass all in chess, we can and should accept the compromise proposals of foreigners without prejudice to ourselves." So, at the meeting Bondarevsky was the main speaker, and I objected to him. The rest were silent. The color and pride of the Soviet people - Petrosian, Spassky, Tal, Stein, Polugaevsky, Boleslavsky - sat side by side, lowering their eyes to the floor. They did not, and did not want to have their opinion on this issue! It did not concern them! Bondarevsky supported Serov, and who supported me - no one. The Stalinists easily won. At the appointed time, the Soviet team came to the game, and the Americans did not appear in full force. The newspapers sounded the brilliant victory of the Soviet Union with a score of 4: 0. But the matter did not end there. How so?! No sooner had Cuba established normal relations with the United States of America, how someone Bondarevsky inflicted a devastating blow to these efforts! The question of the disruption of the match was discussed by the Government of Cuba. Corresponding explanations were sent to Moscow. Order of the Sports Committee - the match must be played! - cooled the fervor of the Stalinists, the leaders of the team. On a special day (all other teams were free) the match was held. The Soviets won 2½-1½.

Tal (with Fischer) sporting his bandage

.

.

The American team

The American team

.

.

"El Ajedrecista en Jefe"

.

.

.

.

.

.

See Michael Goeller's astute observations concerning the implications of this above photo on the Kenilworthian.

Fischer vs. Spassky

Fischer vs. Spassky

.

.

.

.

.

The US has never issued a chess themed stamp.

For the 17th Chess Olympiad, Cuba issued 6 stamps.

The players received a medallion.

The players received a medallion.

.

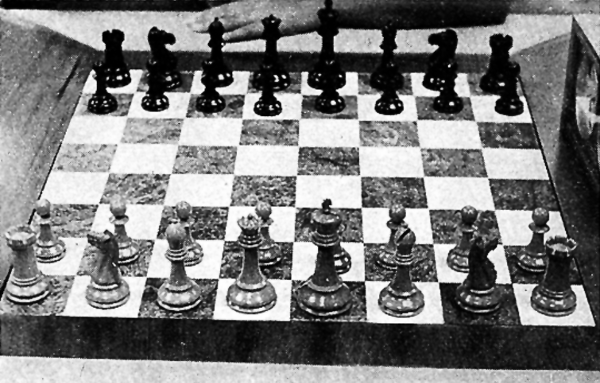

. Players were given a chess set while the team captains also received a marble board.

Players were given a chess set while the team captains also received a marble board.

(see Kevin Spragget's site for some nice photos - HERE)

The players received a box of Cuban cigars and one oversized cigar in a special case.

.

.

The Olympiad closing ceremonies took place on Sunday, November 20. Saturday, November 19 was Capablanca Day, celebrating what would have been his 78th birthday. The organizers planned a massive simultaneous exhibition to show off Cuba's love of chess. 380 masters played 18 opponents each for a total of 6,480 games. It was the largest simul to date. The results were 3,212 wins for the masters vs 144 losses. Of the remaining games, 707 were draws and the rest were unfinished.

Castro playing against Petrosian in the simul.

Castro playing against Petrosian in the simul.

This image shows less than half of the boards

This image shows less than half of the boards

Another look at the Plaza de la Revolución where the simul took place

Another look at the Plaza de la Revolución where the simul took place

.

.

.

.

The closing ceremonies took place in the shadow of the towering Monumento a José Martí in the Plaza de la Revolución.

The U.S. State Department and the FBI took special note of a couple "irregularities" involving Fischer about which they added to their dossier. First was the "international incident" caused by Fischer's refusal to play during times forbidden by his religion despite the fact that this had been negotiated prior to the event. One witness claimed it was an attempt to embarrass the Cuban government. The second irregularity was that Fischer did not return to the U.S. with his team at the conclusion of the Olympiad but stayed in Cuba for 10 day after as an official guest of the Cuban chess organization. This along with a couple private conversations with Castro put Fischer squarely in the FBI's radar.

The FBI agent assumed Fischer practice Judaism but be was rather a member of the Worldwide Church of God.