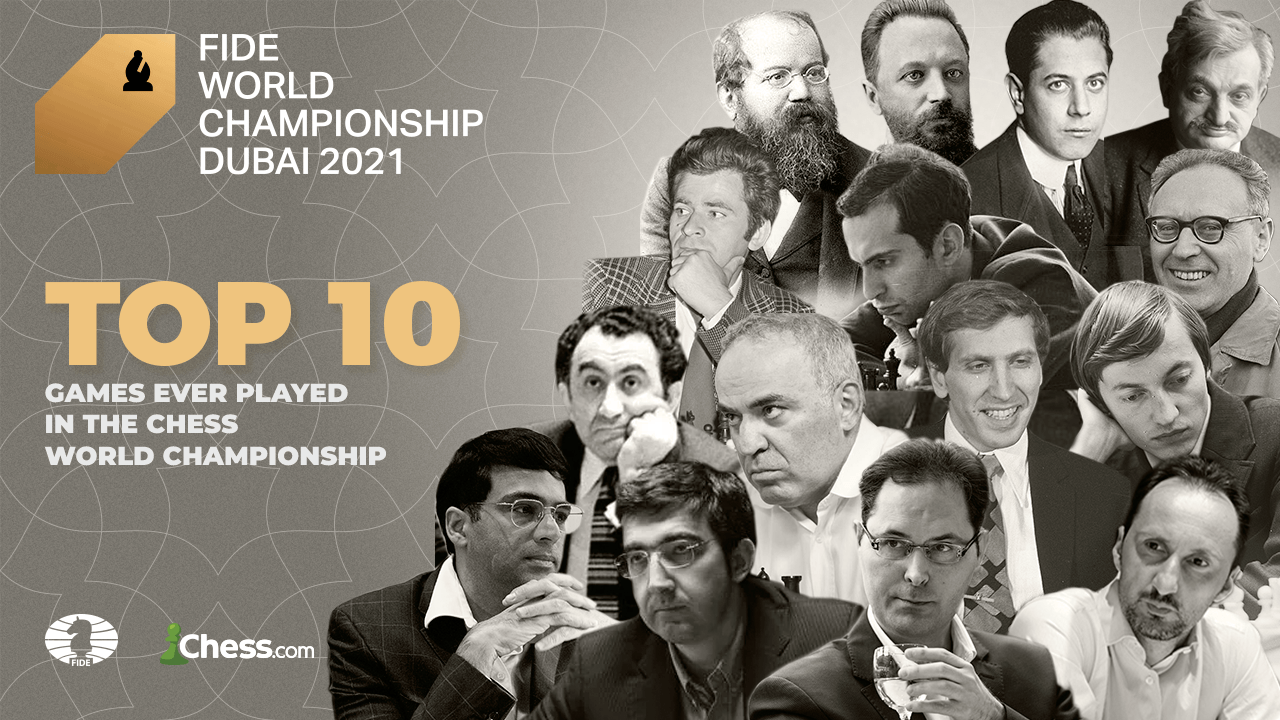

The 10 Greatest Games Ever Played In The World Chess Championship

What is the best game of chess you've ever played? Do you remember where you were: Was it on Chess.com, or over the board? Was it a tournament game, or a more casual affair?

Well, imagine playing a great game on the biggest stage, the FIDE World Championship. It's hard enough to get there—fewer than 40 people have ever played a match for the world championship—and even harder to win, let alone to do so with games that will enthrall millions for decades to come.

These are the 10 greatest games ever played in the world championship.

We ran every game through Stockfish 12 at depth 30 (15 moves per side) using the new Game Review feature. Notes are also greatly helped by the 2021 edition of The Mammoth Book of the World's Greatest Chess Games, in which eight of the ten games below (all except the champion-trying-to-win-last game efforts of 1987 and 2004) are included.

- Steinitz-Chigorin, 1892, 4th game

- Lasker-Capablanca, 1921, 10th game

- Tal-Botvinnik, 1960, 6th game

- Petrosian-Spassky, 1966, 10th game

- Fischer-Spassky, 1972, 6th game

- Karpov-Kasparov, 1985, 16th game

- Kasparov-Karpov, 1987, 24th game

- Kasparov-Anand, 1995, 10th game

- Kramnik-Leko, 2004, 14th game

- Anand-Topalov, 2010, 4th game

- Conclusion

Steinitz-Chigorin, 1892, 4th game

Wilhelm Steinitz became the first official world champion in 1886 by beating Johannes Zukertort. Steinitz defended his title with regularity: 1889, 1890, and 1892 with success before losing to Emanuel Lasker in 1894. Two of these defenses, 1889 and 1892, came against Mikhail Chigorin. Our first game is from the latter match.

For a Romantic-style attacker like Chigorin, getting run over like this must have been a tough pill to swallow. Steinitz's 20.Qf1 is well-celebrated, and he obviously had to see the 24.Rxh7+ and 25.Qh1+ variation to play it. Chigorin missed that idea, also obviously, considering it arrived on the board.

This match also featured one of the worst games in world championship history, which ended up deciding the match in Steinitz's favor.

The Computer Says...

Steinitz played an excellent 95.2 compared to a mere 79.8 from Chigorin. Humorously, the only Steinitz move the computer doesn't like is... yes, you guessed it, 20.Qf1. Stupid silicon, don't ruin our vibe here.

But here's the thing, the machine claims Black's best reply is 20...h5, otherwise he's still losing. Now, who's gonna play 20...h5? You? Chigorin? Me?

Lasker-Capablanca, 1921, 10th game

Jose Capablanca was one of the greatest endgame players ever, and this game is but one example. The match had been close leading up to the game, with Capablanca up 1-0 in nine contests. He went up 2-0 here.

It was the turning point of the match. Emanuel Lasker was not competitive afterward, and one might wonder if this was one time his fighting spirit failed him. Before the match he had even tried to resign the title and play as the challenger, which the chess world did not accept, but it does offer insight into his state of mind entering the match. Capablanca locked it down with two additional victories in the next four games, Lasker simply blundering the exchange to a two-move combination in the last game, and Lasker resigned the match.

The Computer Says...

Capablanca 91.5, Lasker 86.1, a pretty close game.

Capablanca and Mammoth Games annotator FM Graham Burgess both rejected 43...Nb4 because of 44.Rd2 Rb1 45.Nb2 Rxb2 46.Rxb2 Nd3 47.Ke2 Nxb2 48.Kd2. The computer, of course, thinks 43...Rb1 is a mistake and 43...Nb4 is best after all. In this variation, the machine takes things slow on move 45 in that variation, playing 45...Nc6 trying and failing to win the knight as in the 45...Rxb2 continuation.

We humans want and need something more concrete, however, so 43...Rb1 was best in a practical sense. In fact, Lasker certainly played the line that Capablanca and Burgess analyzed as the type of practical trap he was famous for (and sometimes accused of relying on solely for his achievements, which is obviously ridiculous). Can't always listen to the silicon.

Tal-Botvinnik, 1960, 6th game

Easily GM Mikhail Tal's most famous game thanks to the amazing 21st move. It's typical Tal, where the sacrifice may not be "correct" in that it might (or might not!) lose against best play, but it makes it very difficult for a human opponent to find said "best play."

Tal himself actually was not so impressed with the move itself, considering it necessary based on how he'd already played the opening and middlegame. Regardless, with this game Tal was up two points in the match (4-2 including draws). He'd also won the first game and would end up leading the match the entire way, clinching it with a draw in game 21.

The Computer Says...

Be prepared for anything here. This game is always more known for its complexity than its being accurate in every line like a computer would want. So the result of...

...isn't that bad.

The computer considers Nf4 to be inaccurate, but like Tal said, it's all a part of Black's plan. And it worked. Unlike even GM Mikhail Botvinnik, the computer can pretty much see all (usually).

Petrosian-Spassky, 1966, 10th game

Two exchange sacrifices in classic GM Tigran Petrosian style, plus a sick final combination? Yes, please!

Petrosian in 1966 became the first player to outright win a match in defense of his title since Alexander Alekhine did it against Efim Bogoljubow in 1934. Like Tal six years prior, Petrosian's best game put him up 2-0 in a match he never trailed.

The Computer Says...

This is a particularly impressive display by the game report feature, annotating somewhat like a human might. The first exchange sacrifice and the final tactical shot both get the brilliant !! designation, and two additional moves, neither of which are necessarily obvious, get one exclamation mark.

Fischer-Spassky, 1972, 6th game

Poor GM Boris Spassky, we're about to make him the first player to lose two games in this collection.

People remember this game for GM Bobby Fischer uncharacteristically opening with 1.c4. It was also the game that gave him the first lead of the match. What you may not realize is that he used 1.c4 regularly in this match (starting with this game), including his very next game as White, which he also won.

The Computer Says...

Fischer 92.4, Spassky 79.2, but the idea that Fischer only played 92% accurately in this game seems silly. And even though Spassky only played 79% there's no painfully obvious blunder, he just gets gradually run over. By move 26 he hasn't lost any material but the computer gives Fischer a 4.5-point edge, nearly an entire rook's worth.

Karpov-Kasparov, 1985, 16th game

In their world title bouts against each other, GM Garry Kasparov won 21 games and GM Anatoly Karpov took home 19. So it's a little unfair that both games from their matches in this collection are wins for Kasparov. For any Karpov fans, here is our lesson using some of his greatest games.

On the other hand, Game 16 in 1985 is perhaps the greatest game played by anybody in any context.

Like Fischer, Kasparov had broken a tie in the match for a lead he would not relinquish.

The Computer Says...

Now that's the stuff: Kasparov 97.4, against 83.9 for Karpov.

After the inaccuracies 11...Bc5 (which gave Karpov the opportunity, missed, to remove the black knight on b4) and 12...O-O, Kasparov was essentially perfect.

Kasparov-Karpov, 1987, 24th game

Kasparov's other win vs. Karpov is on this list due to circumstance. Lasker probably needed to beat Schlechter in game 10 to keep his title (historians are unsure), but Kasparov definitely did.

The first world championship match between two Soviets to take place entirely outside of the Soviet Union (Seville, Spain, after the 1986 match was split between in London and Leningrad) had ended in a most dramatic fashion.

The Computer Says...

Under the circumstances, the pure pressure that both sides felt—this game is pretty much literally the farthest thing chess has from a random 1|0 bullet game—not the worst, actually.

Kasparov knew what the problem was, too, recounting his main error (move 33) in How Life Imitates Chess from 2007. Those pesky arbiters?

Lost in thought, I was startled by a tap on my shoulder. The Dutch arbiter leaned over and said, "Mr. Kasparov, you have to write the moves." I had become so wrapped up in the game that I had forgotten to make note of the last two moves on my score sheet as required by the rules. The arbiter was of course correct to remind me of the regulations, but what a moment to be strict! Distracted, I played my queen to the wrong square. I missed a subtlety and failed to see why a different move with the same idea would have been stronger. My move gave Karpov a clever defense, and suddenly he was one move from reclaiming his title. But under pressure from the clock, he missed the best move (though our exchange of errors would not be discovered until well after the game), and the momentum was still with me.

Kasparov-Anand, 1995, 10th game

Are three Kasparov games too many? Well, this game features some ridiculous opening preparation from Kasparov: He played his first 21 moves in less than five minutes, while the usually quick GM Viswanathan Anand needed most of his time.

It was also an important game in the match: After eight draws, Anand had just taken the lead in game nine, only for Kasparov to cruelly snatch it away, then win games 11, 13, and 14 as well while never losing again. Turned around by one piece of opening prep.

Kasparov's opponent five years later, who worked with him in this match, GM Vladimir Kramnik, knew not to play this variation of the Ruy Lopez against him.

The Computer Says...

Kasparov 97.3, Anand 87.2. As with Petrosian-Spassky, the computer's assignments of !! and ! markers are particularly strong.

Kramnik-Leko, 2004, 14th game

Like the 1987 Kasparov-Karpov game, Kramnik was a draw away from losing his title. Kramnik responded with a positional masterpiece, gradually accumulating advantages all over the board.

A situation like this may never happen again. It was the last world championship match to date that did not have a rapid tiebreak provision, and it's hard to imagine a future circumstance where that might be reverted.

The Computer Says...

Instructively, the computer isn't the biggest fan of several of GM Peter Leko's exchanges: 8...Bxc5, 15...Nxd4, and 16...Qxd2+. Needing only a draw to become world champion, it's understandable that Leko would be anxious to exchange, but the ones he went for tended to help Kramnik's position. 24...Nf4, aiming for another exchange, is the losing blunder by allowing 25.b6 and a White outpost on c7.

Anand-Topalov, 2010, 4th game

The Catalan is supposed to be a long-term, positional opening. Anand says never mind all that and crushes GM Veselin Topalov's king.

Anand went up 2-1 with this game and although Topalov came back to tie the match in game eight, Anand won the 12th and final game to take the match. It closed the book on a long road for Anand to solidify his claim to the title—he had to win a tournament in 2007 to become champion, then in 2008 beat Kramnik who lost his title without a match, then in 2010 beat Topalov who lost his spot in the 2007 tournament by losing to Kramnik.

The Computer Says...

The losing move is given as 22...Rad8, which gets no negative marking in the Mammoth Book although the computer's favorite move, 22...Qe7, is not considered among the three alternatives analyzed by Burgess. Chess is hard.

Conclusion

Well, winning the whole match is clearly a good way to have your games remembered: the match victor took all 10 games here. Of course, by definition, there are more total games to choose from when looking for players who won the match compared to those who lost the match!

You may notice that GM Magnus Carlsen did not have any games on this list. He certainly provided good candidates, but he's also played the shortest world championship matches in history, giving him fewer opportunities. In four matches he's won seven classical games. (And lost just twice!)

Fortunately for Carlsen and GM Ian Nepomniachtchi, there will soon be opportunities to produce the next world championship masterpiece.

What are some of the best games that didn't make the cut? Let us know! And be sure to catch the World Chess Championship and witness the next great game on Chess.com!