|

The Introduction:

The second half of the 18th century into the early 19th century was marked with cultural changes previously equaled perhaps only by the Renaissance. There were great and important political revolutions, such as those in America and France; there was the Industrial Revolution that changed the way people produced goods, which in turn changed the way they lived and how they viewed the world; there were great strides made in science and technology and there was a major trend against the status quo, a trend that put reason above dogma and science above simple faith. This was the beginning of Rationalism ——> the Age of Reason ——> the Enlightenment. Ironically enough, even among the "enlightened" individuals, Jews were still considered a lower class of people. Some of this attitude changed through the philosophical efforts of enlightened Jews such as the teacher Joseph Perl, author Saul Berlin, and the epicenter himself of the Haskala, the Jewish enlightenment that followed on the heels of the Age of Reason, Moses Mendelssohn.

The Haskala was an internal affair for Jews which tried to bring Jews out of their self-contained, "ghetto" mentality to assimilate into the world around them. But along with this movement, there was also a necessary one, initiated by gentiles, that tried to convince the world to accept these Jews.

And it's within this tumultuous time this story begins.

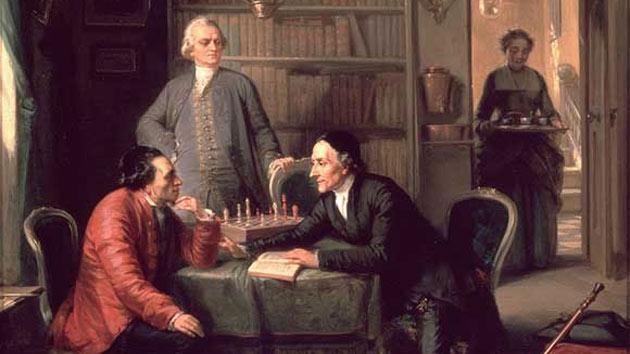

The panting below was created by one of the leading Jewish artists of the Enlightenment, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. This rich allegorical picture tells us a story.

The Characters:

The man in the red coat seated on the left is Moses Mendelssohn, the great Jewish philosopher and spearhead of the Jewish Enlightenment. Mendelssohn enjoyed prominence and almost universal respect during his life, setting an example for both Jews and Gentiles. In his position he conversed and made friends with many other prominent men of different walks of life and of different religions. Two of these men are shown in the picture :

— The man standing is Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a Christian, an author and a rationalist, who believed, and expressed that belief, in religious tolerance. He was one of Mendelssohn's most vocal supporters.

— The man seated across from Mendelssohn is another Christian, named Johann Kaspar Lavater. Lavater was a highly influential cleric, a great speaker and defender of Christianity. A physician's son, he was well known mainly due to his "scientific" writings on physiognomy (he argued, for instance, that the static features of one's face revealed one's moral nature, while the mutable elements, those used for making expressions, could be used to deceive).

The Setting:

Lavater visited Mendelssohn in his home several times for discussions on religion. During the course of those very friendly private visits, Lavater was able to elicit from Mendelssohn certain admissions such as agreeing to Jesus' high moral stature. Mendelssohn considered their meetings an indication of how their friendship transcended their differences. Lavater, however, saw the meetings a chance to strike a religious coup by using them to force Mendelssohn, the most famous Jew, to convert to Christianity.

The Intrigue:

One day Mendelssohn opened his mail to find a book, a copy of Charles Bonnet's "Palingénésie Philosophique" that had been translated by Lavater. The gift, however, was double edged. The translation included a dedication — to Mendelssohn — in which Lavater revealed some of their private conversation and then used what he culled to issue a public challenge, an ultimatum, to Mendelssohn that he either refute Bonnet's "truths" on the validity of Christianity or do the only honorable thing and convert. But honor was already on Mendelssohn's side and he was deeply hurt by Lavater's betrayal of what Mendelssohn thought was a friendship. The affair strirred a lot of interest and most people agreed with Mendelssohn's refusal to even consider Lavater's challenge. In fact, Mendelssohn used his reply to Lavater to show how Judaism was a religion of tolerance while Christianity, at least Lavater's brand, was out of touch with the ideas of the Enlightenment. Eventually Lavater's reputation, as both a theologian and a scientist, suffered irreparable damage.

The Interpetation:

The the entire affair was good for the Enlightenment and for the Haskala but the strain severely deteriorated Mendelssohn's health.

The painting depicts an attentive Mendelssohn, a fervent Lavater and a seemingly disapproving Lessing. Apparently Lessing had originally been seated on the other side of the chessboard from Mendelssohn. Lessing was introduced to Mendelssohn by Aaron Salomon Gumpertz who was Mendelssohn's mentor, initially as a chess player. Through chess, their friendship blossomed. The chessboard in the painting symbolizes that friendship.

Much has been made by scholars of the chessboard itself.

According to Cyril Reade in his 2007 treatise, "Mendelssohn to Mendelsohn"—

Sed-Rajna suggests that 'the chess pieces show that Mendelssohn is winning' in his exchange with Lavater. . . .

The play of the chess pieces could reflect Oppenheim's interpretation of the relative intellectual position in this exchange about religious beliefs. The players on the chessboard include six white pieces opposing two red pawns and the King. The white castle on the last row and the queen on the next to last have put the red king isolated on the last row in checkmate. Thus the white player has put the red in checkmate. The chessboard victory needs to be examined in terms of the play of light and dark in the painting.

. . .

The allegorical play of light and dark that distinguishes the good, Mendelssohn and Lessing, from the bad, Lavater, echoes the alignment of the dark and light chess pieces, a dichotomization that evinces simplistic moral positions, clothed in sophisticated language of history paining. By reading the checkmate as a victory of the light side — of the truly enlightened position — it is possible to

understand Oppenheim's painting as having attributed the win in the Lavater affair to Mendelssohn.

The book in Lavater's hand is his translation of Bonnet's book. Above the doorway is a blessing (in Hebrew - ברוך אתה בבואך וברוך אתה בצאתך ) from Deuteronomy 28: 6: "Blessed shalt thou be when thou comest in, and blessed shalt thou be when thou goest out."

The Prologue:

Lessing was a writer. His play, "Die Juden," used Gumpertz as a model. Later, his play, "Nathan the Wise," used Mendelssohn as a model. "Nathan" was banned by the Catholic Church during his lifetime. Later, both plays were banned by the Nazis.

In a letter to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Carl Friedrich Zelter had written—

Jan. 19, 1826

I remember in my younger days a Jew of the name of Michel, who appeared to be mad on all subjects, except two. When he spoke French, every word came trippingly from his tongue, and he was a first-rate chess-player. Now this "mad Michel" (as they called him), pays a visit to old Moses Mendelssohn, while he is sitting at chess with Abram, the old mathematician, and begins to watch the game.

Abram at last makes a gesture with his right hand, showing that he gives up the game for lost, and gets such a thumping whack on the head, that his loose wig tumbles off. Abram quietly picks it up, saying, "But, my dear Michel, how ought I have moved then?"

Lessing has copied the incident in "Nathan," and now I am about it, I may as well tell you the rest. Abram, the aforesaid arithmetician, is the very man whom Lessing took as his model for Alhafi. He passed for a very great oddity, and a very great arithmetician, giving lessons for a few Groschen, for gratis, and he had a room in Mendelssohn's house, gratis too. Lessing highly esteemed him on account of his piety, and his innate cynicism. When Lessing went to Wolfenbiittel, Abram begged of him a rare book on mathematics from the local Library. Lessing found two copies, and sent one of them to Abram, to keep as a souvenir. Some time afterwards, Abram comes to Mendelssohn, bringing the book, and wants to present him with it.

"Why, you surely do not want to part with that book; it's a keepsake from a friend."

"I know that, but I do not want it any more; the examples are good, and I do not understand Greek."

"Well, I see you want money; tell me, how much ? "

"No, no, I have money, and don't want any."

"Well then, go, in God's name, and if you want anything, you know where I live!"

A short time afterwards, Abram comes to Mendelssohn, who happens just then to have Professor Engel with him; he stands quite still, without uttering a word.

"Well, Abram, how are you ? Why are you so silent, and what do you mean by staring at me in that way ? do you want anything?"

"My wife has arrived from Hanover; I have but one chair,"

—whereupon he seizes a chair and bolts with it out of the room. His wife lived in Hanover with her relations, for her husband never had a farthing.

It was good fun, hearing Professor Engel tell these stories, and others like them, he being a thorough cynic about good eating, drinking, and sleeping.

Now good-bye; may our little fish tickle your palate as pleasantly as your toothsome pheasants did ours!

Yours,

Z

According to the "Life of Goethe" by Heinrich Düntzer in 1883, Goethe was a chess player:

These four - Goethe, Horn, Crespel and Riese - used to play chess on a great double board which belonged to Riese.

One of the results of the Enlightenment was the rise in popularity of coffeehouses where intellectuals gathered. In his most famous book, "Rameau's Nephew," Diderot wrote:

"If the weather is too cold or too rainy, I take refuge in the Café de la Regence. There I amuse myself by looking on at the Chess. Paris is the place in the world, and the Café de la Regence the spot in Paris, where this game is best played; it is at Rey's that the profound Légal, the subtle Philidor, the solid Mayet fight their battles, that we see the most surprising moves and hear the poorest conversation.

For if it is possible to be a man of wit and a great Chess-player like Légal, it is also possible to be a great player and a simpleton like Foubert and Mayet."

. . .

"He [Rameau's nephew] comes up to me. 'Ah ! here you are, monsieur le philosophe; and what are you doing here among this crowd of idlers. Are you too wasting your time in pushing bits of wood?'

I: No, but when I have nothing better to do, I amuse myself with looking on for a moment at those who push them well.

He: In that case you can very seldom be amused. Except Légal and Philidor, nobody else knows anything about it.

I: How about M. de Bissy ?

He: As a Chess-player he is what Mlle. Clairon is as an actress: both know all that can be learnt of their respective arts.

I: You are hard to please. I see you have no mercy except for the first-rates.

He: Yes, at Chess, at draughts, in poetry, in eloquence, in music and other such nonsense. What is the use of mediocrity in such things ?

I. Very little, I confess. But the fact is that a great many men must apply themselves to it in order that the man of genius may come out. There is one such every now and then. But let us change the subject."

Inexplicably, Steinitz wrote (in "The Modern Chess Instructor," 1889):

"Some of the foremost thinkers have spoken in the highest terms of the game of Chess as an intellectual amusement and as a mark of great capacity, and some~of the greatest celebrities of different nations has devoted time and attention to the study and practice of its intricacies. Goethe, in his translation of " Le Nepheu de Rameau," [Le Neveu de Rameau] by Diderot, endorses the opinion of the celebrated French philosopher who describes it as "the touchstone of the human brain."

Goethe did translate "Le Neveu de Rameau," but didn't offer the above endorsement in that book, neither did Diderot.

However Goethe did write an earlier work called "Gotz von Berlichingen," based on the memoirs of a 16th century adventurer, Götz von Berlichingen or Götz of the Iron Hand (because of his functioning metal prosthesis for an arm lost in battle). He fought in numerous feuds for himself and others, one of which was against the Bishop of Bamberg.

In "The Goethe gallery: from the original drawings of Wilhelm von Kaulbach," 1881. Kaulbach provided the drawing below along with the following:

In the drama [Goethe's "Gotz von Berlichingen"], Adelheid, a fascinating and unscrupulous beauty, is plotting the destruction of Gotz through his friend Adelbert von Weislingen. The artist has illustrated the scene in which the heroine is engaged in a game of chess with the Bishop of Bamberg. Franz, the lovesick squire, and the Abbot of Fulda, "the wine-butt," look on. While the old bishop is apparently absorbed in the game, Liebtraut, the minstrel, is playing on the lute and singing.

Adelheid to the Bishop: Your thoughts are not in your game.

Check to the king!

Bishop Bamberg: There is still a way to escape.

Adelheid: You will not be able to hold out long.

Check to the king!

Liebtraut: Were I a great prince, I would not play this game, and would forbid it at court and throughout the whole land.

Adelheid: 'Tis indeed a touchstone of the brain.

Checkmate!

________________________________________________________________

Thanks to my erstwhile cohort, the Bishop Berkely, for the idea and for having brought much information to my attention.

reference:

"Nathan the Wise by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing," translation by Dr. Adolphus Reich.

"Diderot and the Encyclopædists" (includes a translation of "Rameau's Nephew")

by John Morley, 1878.

"The Modern Chess Instructor" by William Steinitz, 1889.

"The Goethe Gallery: from the original drawings of Wilhelm von Kaulbach" by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1881.

"Life of Goethe" by Heinrich Düntzer, 1883.

"Goethe's letters to Zelter," Volume 13, 1887.

"Mendelssohn to Mendelsohn: visual case studies of Jewish life in Berlin" by Cyril Reade, 2007.

"White King and Red Queen: How the Cold War Was Fought on the Chessboard" by Daniel Johnson, 2008.

"A History of Zionism" by Walter Laqueur, 2003.

|