Chess Olympiad Dream Teams

In honor of the 44th Chess Olympiad, we at Chess.com asked the question: If you could put every country's best five players ever on the same team, how good would those teams be?

Now there are many arguments, and not just in chess, about how good players of the past really are. But for this article, we try to avoid that speculation and just look for success in a player's own time. That said, we also try for a chronological balance, going for strength across eras instead of putting every egg in a 19th- or 21st-century basket.

Which country will team together and win the gold? Just one way to find out! You can watch the 2022 Olympiad live on Chess.com/TV and on our Twitch, or catch all our live broadcasts on YouTube.com/ChesscomLive. You can also keep up with all the details and watch the broadcast on our live events platform.

Each team is presented as both a graphic and a table. Table notes: WCC=World Chess Championship. Peak ranking uses ChessMetrics.com before 2000. An asterisk (*) after WCC Challenger means the player negotiated or earned the right to play for the title, but the match was never played.

Now, the teams:

- Russia (Kasparov, Karpov, Kramnik, Alekhine, Botvinnik)

- United States (Fischer, Caruana, Nakamura, Morphy, Reshevsky)

- Hungary (Polgar, Portisch, Leko, Rapport, Maroczy)

- Ukraine (Bronstein, Ivanchuk, Geller, Bogoljubow, Ponomariov)

- Poland (Rubinstein, Tartakower, Najdorf, Duda, Wojtaszek)

- Germany (Lasker, Anderssen, Tarrasch, Hubner, Unzicker)

- Netherlands (Euwe, Timman, Giri, Van Wely, Donner)

- Armenia (Petrosian, Aronian, Vaganian, Akopian, Sargissian)

- Latvia (Tal, Shirov, Nimzowitsch, Koblencs, Klovans)

- England (Short, Adams, Blackburne, Staunton, Nunn)

- China (Ding Liren, Wang Hao, Yu Yangyi, Wei Yi, Wang Yue)

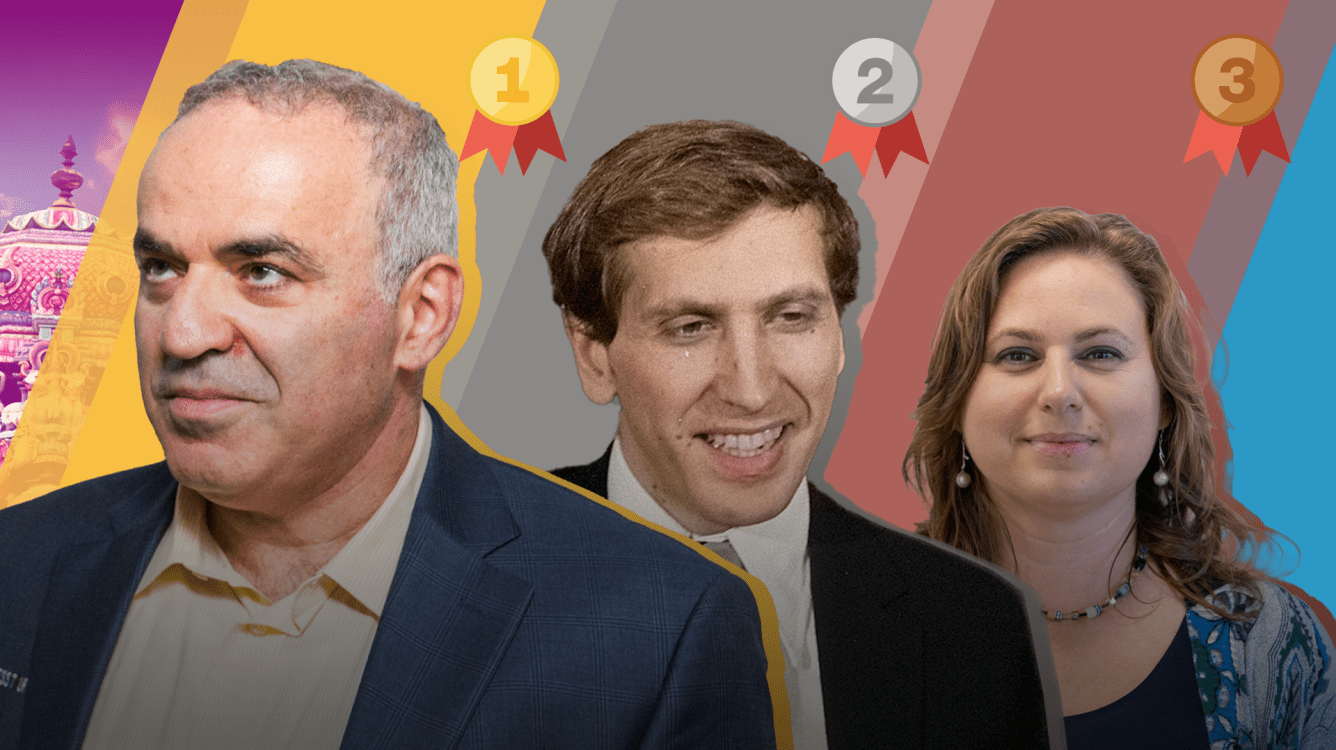

#1: Russia

Despite the government's current policies, the chess is no contest. No other country can come even close to filling up their whole team with world champions.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Garry Kasparov | 1963 | 1st | World Champion (6x) |

| 2 | GM Anatoly Karpov | 1951 | 1st | World Champion (5x) |

| 3 | GM Vladimir Kramnik | 1975 | 1st | World Champion (3x) |

| 4 | Alexander Alekhine | 1892 | 1st | World Champion (4x) |

| 5 | GM Mikhail Botvinnik | 1911 | 1st | World Champion (5x) |

When you have not one but two reserves who were also the world champion, GMs Vasily Smyslov and GM Boris Spassky, you're the best chess country. Not to mention incredibly strong players who were never world champion like Mikhail Chigorin or GMs Viktor Korchnoi, Ian Nepomniachtchi, and Peter Svidler.

If you want to assign different countries to these players, it would be simple enough for most of them: Kasparov and Kramnik can go to Armenia and Ukraine, respectively, which was the nationalities of their mothers; Alekhine can play for France, where he was a citizen after 1927; and Botvinnik was born in what was at the time the Grand Duchy of Finland, albeit part of the Russian Empire in what is now St. Petersburg, Russia, and in a city where he never lived permanently.

The bar to entry into Russia's top-five chess players is stratospherically high, but one active player has a chance to join it. That would be Nepomniachtchi, who has won two consecutive Candidates Tournaments. But he needs to become the world champion and defend multiple times, preferably against GM Magnus Carlsen in at least one match, to join this prestigious list.

No one else would seem to have a reasonable shot. Even super GM Andrey Esipenko, currently 20 years old, would need an absurdly good next decade. He needs multiple world championships and hasn't come particularly close to qualifying for a Candidates Tournament yet.

#2: United States

You can try to put another country second, but good luck making the argument. Players who don't make this team but would easily be in most other countries' top fives include: GM Wesley So, GM Gata Kamsky, GM Pal Benko, GM Reuben Fine, Frank Marshall, and Harry Pillsbury. Instead, they give way to:

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Bobby Fischer | 1943 | 1st | World Champion (1972) |

| 2 | GM Fabiano Caruana | 1992 | 2nd | WCC Challenger (2018) |

| 3 | GM Hikaru Nakamura | 1987 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (2x) |

| 4 | Paul Morphy | 1837 | 1st | World Champion (unofficial) |

| 5 | GM Samuel Reshevsky | 1911 | 1st | T-3rd, 1948 World Championship |

Fischer at number one is obvious even if he might have trouble getting along with all these scary new people away from the board. After him, positions two through four could really go in any order you want depending on how exactly you weigh the measurements you value. And Reshevsky rounding out the squad is one of the strongest board-five players.

If So makes a big leap in the next championship cycle, he might be able to join Caruana and Nakamura on the all-time U.S. team. Also worth following is development of the youngest grandmaster ever, GM Abhimanyu Mishra, 13, and it is not too late for 21-and-under GMs Jeffery Xiong (rated 2691), Hans Niemann (2688), and Sam Sevian (2684) to make an impact.

#3: Hungary

The third-best or "bronze" position is a tough call between two or three countries, but Hungary takes the cake. The more difficult question is how to sort their top four boards, as almost any order works.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Judit Polgar | 1976 | 8th | 2005 FIDE Championship Challenger |

| 2 | GM Lajos Portisch | 1937 | 3rd | WCC Candidate (8x) |

| 3 | GM Peter Leko | 1979 | 4th | WCC Challenger (2004) |

| 4 | GM Richard Rapport | 1996 | 5th | WCC Candidate (2022) |

| 5 | GM Geza Maroczy | 1870 | 1st | WCC Challenger (1906*) |

Maroczy beats Gyula Breyer, GM Gyula Sax, GM Laszlo Szabo, GM Zoltan Ribli, and Benko (who would be a better fit on the U.S. anyway) for the last spot on the strength of his number-one peak position in 1906, when he was ready to challenge for the world championship until negotiations fell through.

The bar is very high, and the only other Hungarian player who would seem to have a chance now of getting there someday is GM Benjamin Gledura, currently rated 2637 at age 22, but his chess would need to take a big leap.

4th: Ukraine

Ukraine is pretty close to Hungary in all-time chess talent after you account for two Soviet players who were born and raised in Kyiv. After the top five, Ukraine runs out of gas a bit (their first reserve may be someone like GM Anton Korobov), but five is all they need in this exercise.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM David Bronstein | 1924 | 1st | WCC Challenger (1951) |

| 2 | GM Vasyl Ivanchuk | 1969 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (3x) |

| 3 | GM Efim Geller | 1925 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (6x) |

| 4 | GM Efim Bogoljubow | 1889 | 1st | WCC Challenger (2x) |

| 5 | GM Ruslan Ponomariov | 1983 | 6th | FIDE Champion (2002) |

Bronstein gets first board, but Ivanchuk would be completely at home there too—peaking in the top two while Kasparov and Karpov were in their primes (1992) is a feat few can claim. Geller could also work on the first board, especially if Team Ukraine wanted to use his terrific score against Fischer (+5 -3 =2) to their advantage. Bogoljubow gets a bad rap (including from this author at times) for getting the unjustified 1934 rematch against Alekhine but was the unofficial world number-one for a time. Ponomariov on board five often gets lumped in with the supposedly weaker FIDE champions from 1999 to 2004, but he peaked as the world number-six, better than any fifth board on the teams ranked below Ukraine.

Ukraine currently has some strong young players, but it's hard to see any of them cracking the all-time top-five down the line, if only because of how high the bar has been set. GMs Kirill Shevchenko (age 19 rated 2654) and Illya Nyzhnyk (age 25 rated 2686) may have the best opportunities.

5th: Poland

Poland is historically a superb chess country, but their present-day status isn't as high. And while they rank behind Ukraine, Poland has a deeper bench, featuring Johannes Zukertort and David Janowski, two world championship challengers who both could argue for a spot ahead of Wojtaszek.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Akiba Rubinstein | 1882 | 1st | WCC Challenger (1914*) |

| 2 | GM Savielly Tartakower | 1887 | 3rd | 1st at Vienna (1923) |

| 3 | GM Miguel Najdorf | 1910 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (2x) |

| 4 | GM Jan-Krzysztof Duda | 1998 | 12th | WCC Candidate (2022) |

| 5 | GM Radoslaw Wojtaszek | 1987 | 15th | World Youth Champion (2004) |

Although Najdorf's career peak came as a citizen of Argentina, he had no real choice but to stay out of Europe at the beginning of World War II in 1939. Fortunately he, along with Tartakower, was playing in the Buenos Aires Olympiad at the time. Reaching a Candidates Tournament helped Duda a lot, but his seventh-place finish keeps a fairly sizable gap between Najdorf and himself for fourth.

Even as older players, Rubinstein, Tartakower, and Najdorf set quite a standard in Polish chess. With Duda already a Candidate once and on the all-time team, this roster seems set for quite some time. IM Pawel Teclaf, age 19, is the only player younger than Duda in Poland's current top-20 players, but Teclaf is rated just 2548.

6th: Germany

The German team has three players born before 1900, more than anyone, and nobody born since the 1940s. So it's a good time to discuss that age-old argument in sports: How would the players of yesteryear fare in the modern day? The generally accepted answer is, if you just transported them to now with no adjustment period, they would fail, but if you took someone with the same natural talent and then let them grow up and develop with modern amenities, they'd succeed. That answer is generally accepted because it's probably true, and that's why players like Morphy make a team.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | Emanuel Lasker | 1868 | 1st | World Champion (6x) |

| 2 | Adolf Anderssen | 1818 | 1st | World Champion (unofficial) |

| 3 | Siegbert Tarrasch | 1862 | 2nd | WCC Challenger (1908) |

| 4 | GM Robert Hubner | 1948 | 6th | WCC Candidate (4x) |

| 5 | GM Wolfgang Unzicker | 1925 | 14th | T-1st at Moscow (1965) |

After the incredibly easy pick of Lasker for the first board, decisions on Team Germany become very tough. In 1981, Hubner came ever-so-close to challenging Karpov for the world championship, but it's not enough to give him the edge over his 19th-century predecessors. Meanwhile, Unzicker—whom Karpov once dubbed the "world champion of amateurs"—rounds out the squad, barely beating out another Wolfgang U., GM Wolfgang Uhlmann.

He's not there yet, but 17-year-old GM Vincent Keymer is already rated 2686 and has the talent to become the all-time German number-two sometime down the line, or if not that high a position, certainly the top five. Naturally, there is still a way to go.

7th: Netherlands

If there's ever a country whose world champion does not get the first board, it's the Netherlands, Timman's career was so strong. But he also had the misfortune of playing at the same time as Kasparov and Karpov and so never reached number one, something Euwe did accomplish even though he faced some all-time greats himself.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Max Euwe | 1901 | 1st | World Champion (1935) |

| 2 | GM Jan Timman | 1951 | 3rd | Challenger (FIDE 1993) |

| 3 | GM Anish Giri | 1994 | 3rd | WCC Candidate (2x) |

| 4 | GM Loek van Wely | 1972 | 10th | T-4th at Wijk aan Zee (2003) |

| 5 | GM Jan Hein Donner | 1927 | 45th | 2nd at Oegstgeest (1970) |

Meanwhile, Giri is the easiest third-board selection of the entire article, and he makes a convincing "big three" with Timman and Euwe. Loek van Wely was once the world number-10, and the last Dutch spot goes to their best player in the roughly 30-year era between Euwe and Timman. Just missing out are GMs Jeroen Piket, Jan Smeets, Ivan Sokolov, and John van der Wiel.

Giri is still looking to move up the list if he does well in the next one or two world championship cycles. GM Jorden van Foreest may actually already be better than Donner, and fourth place on the list could certainly be his at some point as well.

8th: Armenia

The smallest modern-day country in the top eight, with a population of about three million (although the diaspora is at least twice that size), Armenia would rank at least third and possibly second if they pried Kasparov from Russia. (Kasparov identifies as Russian, one reason he's been so stridently anti-Putin long before the 2022 war, but not only was his mother Armenian—his surname is the russification of Gasparyan—he played with other Armenia-adjacent teammates in a 2004 event.)

Even without him, Armenia is fairly easily an all-time top-10 chess country.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Tigran Petrosian | 1929 | 1st | World Champion (2x) |

| 2 | GM Levon Aronian | 1982 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (5x) |

| 3 | GM Rafael Vaganian | 1951 | 3rd | WCC Candidate (2x) |

| 4 | GM Vladimir Akopian | 1971 | 11th | Finalist, 1999 FIDE Championship |

| 5 | GM Gabriel Sargissian | 1983 | 40th | National Champion (2x) |

Aronian may play for the United States now, but he stays on the Armenian team for the all-time tournament and is a clear number-two on this roster. Vaganian, now 70, is an underrated player historically—reaching third in the mid-1980s meant you were playing better than anybody in the world not named Kasparov or Karpov.

The fifth position is somewhat open in coming years if GMs Haik Martirosyan (2672 at 21), Shant Sargsyan (2661 at 20), or Aram Hakobyan (2612 at 21) can make a big leap. No one is going to replace Petrosian and Aronian on the top two boards for some time, though.

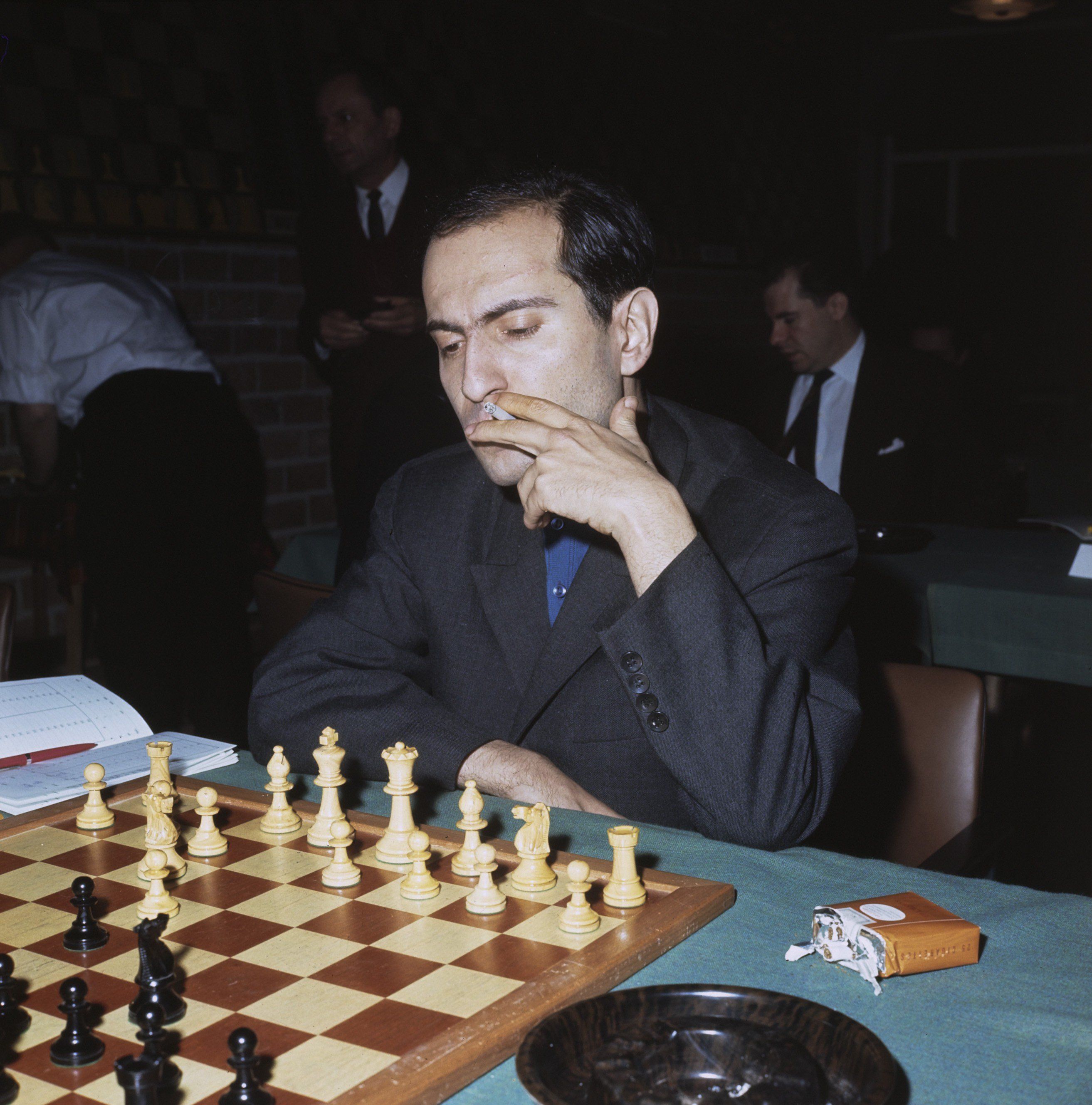

9th: Latvia (or Spain)

It all depends which country Shirov would play for, as he has represented both his native Latvia and adopted Spain for extended periods of time. Like Aronian, Shirov's decision of the country to represent has less to do with any lack of cultural affinity and more with a perceived lack of support from the native government.

Hence, Latvia takes the spot. Spain doesn't have anyone who can really challenge Latvia's first board, either.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Mikhail Tal | 1936 | 1st | World Champion (1960) |

| 2 | GM Alexei Shirov | 1972 | 2nd | WCC Challenger (1998*) |

| 3 | GM Aron Nimzowitsch | 1886 | 2nd | 1st at Carlsbad (1929) |

| 4 | Alexander Koblencs | 1916 | 43rd | National Champion (4x) |

| 5 | GM Janis Klovans | 1935 | 40th | National Champion (9x) |

If it comes down to just three boards, Latvia might have the third-best team in this contest, but they lose a bit of steam at the bottom boards. Tal trusted Koblencs with his world championship preparation, the deciding factor in ranking the bottom two positions.

In an imaginary world where the Baltics are all one state, that team would replace Poland in the top five: Estonia's GMs Paul Keres and Jaan Ehlvest (the latter moved to the United States only in his mid-40s) would replace Koblencs and Klovans.

As for the future, at a two million population, Latvia is even smaller than Armenia. And with no player currently rated above 2600—GM Arturs Neiksans is the number one at 2594—the odds someone improves Latvia's all-time squad in the coming years are slim.

10th: England

This is also the British team—Scotland has had some strong players, perhaps most notably GM Jonathan Rowson, but no one who would make a top-10 British players list.

One of the hotbeds of 19th century chess, England and Britain entered a lull for much of the 20th century. It wasn't until the 1970s that their chess scene took off again.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Nigel Short | 1965 | 5th | WCC Challenger (1993) |

| 2 | GM Michael Adams | 1971 | 4th | FIDE Finalist (2004) |

| 3 | Joseph Blackburne | 1841 | 2nd | 1st at Vienna (1873) |

| 4 | Howard Staunton | 1810 | 1st | World Champion (unofficial) |

| 5 | GM John Nunn | 1955 | 10th | 1st at Wijk aan Zee (3x) |

As the only Englishman to challenge for the world championship, Short claims the first board over Adams even though both players had amazing durability and peaks.

Blackburne was an amazing attacking player with a long and illustrious career in the late 19th century. Staunton, although he has to make the team on account of dominating his peers, was never really tested, even less so than Morphy. England also has one of the deepest benches: GMs Jon Speelman, Tony Miles, and David Howell, and pre-GMs Henry Bird and Fred Yates.

No current young Englishman seems ready to join the world's top-10.

11th: China

China is somewhat the opposite of the Polish and German teams: not much of a history, but they've churned out strong players in the 21st century. So many of them that several stars such as GM Hou Yifan, GM Bu Xiangzhi, and GM Li Chao don't make the team.

| Board | Player | Born | Peak Rank | Top Achievement |

| 1 | GM Ding Liren | 1992 | 2nd | WCC Candidate (3x) |

| 2 | GM Wang Hao | 1989 | 12th | WCC Candidate (2020) |

| 3 | GM Yu Yangyi | 1994 | 10th | T-2nd at Norway (2019) |

| 4 | GM Wei Yi | 1999 | 14th | Youngest 2700 Player (2015) |

| 5 | GM Wang Yue | 1987 | 8th | 5th at FIDE Grand Prix (2008-10) |

China has a great top board, one who will be playing for the world championship in 2023. They also stay extremely strong across all boards but might have some trouble on the middle boards.

As strong as Chinese chess has been in recent times, their current reserve of up-and-comers is a bit lacking. They don't have a single 2500-rated teenager. Wei Yi is still their youngest player rated above 2600 and is already on their dream team.

Honorable Mentions

Despite a dominant world champion on first board, Cuba (Jose Capablanca), India (GM Viswanathan Anand), and Norway (Carlsen) are too shallow overall to make the list. Capablanca could lead a very strong squad from all of Latin and South America, and same thing for a Carlsen-led Scandinavian/Nordic team, but countries were not allowed to combine to create a team for this "contest."

India, meanwhile, would almost certainly have a spot in the top 10 if we ran this exercise again in 20 years thanks to its immense young talents. GMs Arjun Erigaisi, Gukesh D, Nihal Sarin, Raunak Sadhwani, and Praggnanandhaa R are all 18 or younger and all between 2611 and 2689 on the July 2022 rating list. Even if just two of the five reach the uppermost echelons of chess, a team of those two with Anand, GM Vidit Gujrathi, and GM Pentala Harikrishna will be all-time great. Right now, however, the depth isn't there. Mir Sultan Khan arrived from British India and had a career strong enough to be the second board, but he settled in Pakistan post-partition.

Instead, spots 12 and 13 would probably go to the Austrian and Czech teams, led by Wilhelm Steinitz and Richard Reti. France, with Alekhine playing for Russia, doesn't quite have enough firepower to go higher than 14th even with GM Maxime Vachier-Lagrave leading the team. India is looking at a spot around here, somewhere in the top 15. Bulgaria (GM Veselin Topalov on board one), Uzbekistan (GM Rustam Kasimdzhanov), and Georgia (GM Baadur Jobava) would also field somewhat competitive teams.

Favorite Matchups On Every Board

| Board | Player 1 | Player 2 |

| 1 | Kasparov | Fischer |

| 2 | Karpov | Ivanchuk |

| 3 | Nakamura | Nimzowitsch |

| 4 | Morphy | Rapport |

| 5 | Botvinnik | Reshevsky |

First Board: Kasparov vs. Fischer. You know you would pay to see this, especially if you're a fan of the Sicilian.

Second Board: Karpov vs. Ivanchuk. When Karpov's calm, positional style met Ivanchuk's fighting style, the result was almost always a draw as neither player dominated the other. But all of those games involved a post-championship Karpov. How would it play out between two primes?

Third Board: Nakamura vs. Nimzowitsch, if only for the memes after their game starts 1.b3 b6.

Fourth Board: Morphy vs. Rapport. You want to see how Morphy would do against modern players? Rapport is the only active player on a fourth board, and his small idiosyncrasies compared even to modern top chess players could mess with Morphy a bit, too.

Fifth Board: Botvinnik vs. Reshevsky. This board is about who can challenge Botvinnik, and very few can. Even though these two players played several times, seeing them go at it some more would be interesting. The last time they played, four games in 1955, Reshevsky won 2.5-1.5.

Conclusion

If Russia didn't win this mythical competition, it would be a shock, although the United States on a good day could get somewhat close to gold. Hungary and Ukraine would fight hard to make the top three, with a chance at silver. The bronze medal would be very wide open, and actually any of the 11 countries would have a chance at it.

What do you think? Which teams would win medals in this event? Which countries and players deserve a spot but don't get one, or vice versa? And who will win the actual 2022 Olympiad? Let us know in the comments your answer to these and other related questions!