Capt. Bertin's Gambit

The Cunningham Defense in the King's Gambit Accepted begins 1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 Be7. White moves the Bishop to give his King a place to go with 4. Bc4. If Black continues with the threatened 4... Bh4+ and White replies with 5. g3, he has just initiated the Bertin Gambit.

Almost invariably the play continues as such:

A quick look will show that Black has all 8 pawns while White has only 5 and that White has compromised his King somewhat. A second look will reveal that White has developed astonishingly well and has established many potential threats against Black's King, while Black has been gobbling up the three pawns (equivalent in value to an entire minor piece). The question each side is left to answer is whether or not White is adequately compensated.

Slaughter's Coffee-house

Slaughter's Coffee-house

Captain Joseph Bertin was born in the late 1600s in the village of Castelmoron-sur-Lot which lies between Bordeaux and Toulouse in the south of France. In his early 20s, he moved to England and became a naturalized citizen. Bertin played chess in the famous Slaughter's Coffee House on St. Martin's Lane (where later both Philidor and Stamma as well as Alexander Cunningham would also play).

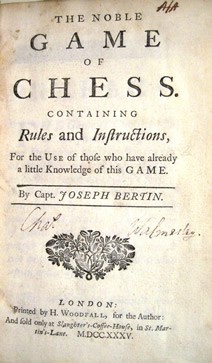

Bertin, just prior to his death, self-published a book entitled, "The Noble Game of Chess: Containing rules and Instructions, for the use of those who have already a little knowledge of this game," "printed by H. Woodfall, for the author, and sold only at Slaughter's-Coffee-House, in St. Martin's-Lane." In this book Bertin examined 26 games of various kinds, 12 endgames and offered a section of general advice or guidelines that should govern how one should conduct a game. Among the games is the first mention of the Three Pawn's Gambit, later called the Cunningham Defense by Philidor in 1749 and given more in depth treatment by the Anonymous Modense (Ercole del Rio) in 1750. Below are the "laws" of chess given by Bertin:

Preface.

The Game of Chess consists of two parts, the Offensive, and Defensive; the Offensive consists in oppressing and routing, as much as possible, your adversary's forces; the Defensive, in the due position of your own, by guarding against your enemy's attack. 'Tis a Game of genius and stratagem, and the proper emblem of war, by which two armies are drawn up in order of battle.

This noble Game abounds with a greater variety of fine strokes, than any other Games which depend on design only, and is therefore more likely to give pleasure to those who study it.

Having been in several Countries, I have seen many Chess-Players, but very few good, for want of knowing how to open well their game; for which reason, I have given particular instructions in this book, how the player may make the proper openings, to attack or defend.

Rules To Be Observed In Playing The Game Of Chess.

I.—The King's Pawn, the Bishop's Pawn, and the Queen's Pawn, must move before the Knights; otherwise if the Pawns move last, the game will be much crouded by useless moves.

II.—Never play your Queen, till your game is tolerably well opened, that you may not lose any moves; and a game well opened gives a good situation.

III.—You must not give useless checks, for the same reason.

IV.—When you are well posted, either for attack or defence, you must not be tempted to take any of your adversary's men, which may divert you from the main design.

V.—Do not Castle, but when very necessary, because the move is often lost by it.

VI.—Never attack, or defend the King, without a sufficient force; and take care of ambushes and traps.

VII.—Never croud your game by too many men in one place.

VIII.—Consider well before you play, what harm your adversary is able to do you, that you may oppose his designs.

IX.—To free your game, take off some of your adversary's men, if possible for nothing; tho' to succeed in your design, you must often give away some of your own, as occasion serves.

X.—He that plays first, is understood to have the attack. When your game is well opened, you must endeavour to attack in your turn, as soon as you can do it with safety.

But the defence, if well played, is still the best against the gambets, in which you change all your pieces, except the gambit that gives three Pawns, which will be necessary to keep a Rook, to conduct your Pawns to the Queen.

XI.—A good player ought to foresee the concealed move, from three to five and seven moves. The concealed move is a piece that does not play for a long time, but lies snug, in hopes of getting an advantage.

XII. —At the beginning of a game, you may play any Pawn two moves, without danger.

XIII.—The gambit is, when he that first gives the Pawn of the King's Bishop, in the second move for nothing, the other keeps it, or takes another for it, if he is obliged to lose.

XIV.—The close-game is, when he that plays first gives no men, unless to make a good advantage; but in giving a Pawn first he loses his advantage.

XV.—He that Castles first, the other must advance his three Pawns, on the side of his adversary's King, and back them with some pieces, in order to force him that way, provided his own King, or pieces, are not in danger in other places.

XVI.—When your game is well opened, to gain the attack, you must present your pieces to change; and if your adversary that has the attack, refuses to change, he loses a good situation; and either in exchanging, or retiring, the defence gets the move.

XVII.—For example: In the beginning of a game, to shew the necessity of playing the Pawns before the pieces, if there were but two Pawns on each side on the board, that is to say, the Pawns of the Rooks, the first that should play would soon win the game, by taking the other's pieces by check; and that situation may come in less number of pieces.

XVIII.—To play well the latter end of a game, you must calculate who has the move, on which the game always depends.

XIX.—To learn well and fast, you must be resolute to guard the gambit Pawn, or any other advantage against the attack; and when you have the least advantage, you must change all, man for man. A draw-game shows both sides played it well to the last move.

The observance of these Rules will be of great use in the practicing of the game, and will prevent your making any useless moves. I wish I could give Rules to avoid over-sights.

In January 1853, Howard Staunton covered the Bertin Gambit in this short article in "The Chess Player's Chronicle." :

Captain Bertin's little volume is of far greater value to us, as it introduces the opening so well known by the name of the Cunningham Gambit. It is remarkable, that almost all the debuts, which bear the name of some particular player, are found upon examination to be the invention of a different person. This is the case equally with the Muzio, Salvio, Allgaier, and Cunningham Gambits. Captain Bertin, who seems to have been its inventor, calls the ingenious opening, which has been popularized by the name of the Cunningham Gambit, the Three Pawn's Gambit, and by this title brings before us its most striking principles. In Bertin's treatise the debut is framed in the following manner:—

It would be idle to say that these are not the best moves that the opening admits, for the same observation might be made respecting all openings, when first made public. The student will of course notice that the second player at his 12th move ought to have moved his K. to Q. second, rather than to his own second. In a variation our author suggests that the first player may at his 12th move take the Rook instead of the Pawn. Besides this, Bertin gives us several variations, beginning at the seventh move of the second player. In one of them, (the first six moves being the same as in the preceding opening,) the moves run: —

And, as our author naively adds, " the players may finish the game." In addition to 8. P. to K. fifth for first player, Bertin also suggests 8. P. to Q. fourth; but his combinations on this move are not very interesting. We cannot say that this writer deserves much praise in his other debuts, but we have proved sufficiently, that it was from his treatise that the theory of the Cunningham Gambit first arose. Captain Bertin's work is a small octavo volume, and contains but 78 pages. It was published in 1735, and sold only at Slaughter's Coffee-house in London, where a Chess Club then held its meetings.

The interesting opening invented by Captain Bertin received a careful consideration from Stamma, a native of Aleppo, the next writer upon the theory of Chess. Taking as his basis his predecessor's ingenious moves of: —

If in this opening the first player at move 11 advance his Pawn to K. fifth, with the view of winning a piece, he will be met by Q. to her fourth (check) and be compelled to interpose his Kt., and thus give his opponent time to extricate his piece from danger. As the first player's Bishop, instead of capturing the Pawn at his 9th move, may retreat to Kt. third, Stamma gives the following variation:—

There are a few issues worth mentioning. Sometimes the moves of the Bertin Gambit were called the Cunningham Gambit since that was Philidor's terminology. The Cunningham Gambit was "usually" the same as the Three Pawns' Gambit, but not always. The term "Cunningham Defense" is never mentioned pre-20th century. Even the term "Cunningham Gambit" wasn't always used to denote the Three Pawns' Gambit, but sometimes just the moves up to 4... Bh4+ (see "Synopsis of Chess Openings" by William Cook, 1884). The fact is that there are many variations that follow 1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 Be7 and these three opening moves today define the Cunningham Defense.

This gambit has long been suspect. In 1841, George Walker wrote:

The Cunningham Gambit abounds in curious and lively situations. The defence is difficult, unless its routine be strictly adhered to, in which case the attack dissolves, and the sacrifice of the Pawns costs the game. The power of the assault, and the value of one move, are eminently demonstrated by the fact, that if White could castle, as in Italy, leaping King at once to the corner, the Cunningham attack would be strictly sound. Ponziani at one time thought otherwise, and in his first edition gives a perfect defence for second player, even suffering White to castle after the Italian method. Pratt quotes this in his edition of Philidor, but was not aware that Ponziani had offered the strongest proof of recantation, by his later analysis in edition of 1782, in which the first player gets the better game.—"A New Treatise on the Game of Chess"

And in 1883, Edward Freeborough and Rev. Rankin wrote:

After Black's fourth move (B-R5ch) the opening branches in two very different directions. By moving his King to Bishop's square, as in the Bishop's Gambit, the first player may secure a good development, recovering his Gambit Pawn without difficulty; or he may give up three Pawns and add considerably to the strength of his attack. The former is the correct play, the latter leads to the most animated game, and constitutes the Cunningham Gambit proper. It is not quite sound, although extremely troublesome to defend. —"Chess Openings Ancient and Modern"

Now for some games —

[It must be understood that this line, though quite interesting, is a minor one in the rarely-played Cunningham variation of the Accepted form of the also rarely-played King's Gambit. So, even in the 19th century, examples are hard to find and in the 20th century, almost nonexistent, especially at master level. But rarity adds, not subtracts, to the charm.]

We'll start with a trio of games played by Tassilo von der Lasa in the middle of the 19th century. v.d. Lasa was an important theorist, codifier, collector and writer and during his time was considered one of the world's strongest players though he played infrequently.:—

This next game was played between Lionel Kieseritzky and Dr. Hugo-Leonhard Von Guttceit. The great Kieseritzky lost to his 21 year old opponent (not yet a doctor).:—

In the following game the Transatlantic Master, Paul Morphy, played this Bertin Gambit against H. E. Bird while simultaneously playing 4 other recognized masters.:—

Fyodor Dus Chotimirsky beat Rubinstein and Em. Lasker in the 1909 St. Petersburg tournament. Here, the following year, he only had to beat some unremembered amateur with the Bertin.:—

I've included the next three games because I found them amusing, although I doubt the unfortunate Mr. R. Bullock had the same reaction during the first two...—

Mr. Wall gave me a bit of background information on the following game:

I am afraid my game with Randy Bullock wasn't very good. It was a gambit tournament with a fast time control at the Dayton Chess Club. His 9...Ne6? is no good. He should have tried 9...c6 first, then 10...Ng4. I could have simply played 10.Bxb7, winning the exchange. Now 10...Ng4 does give me the exchange. He should have played 10...Bxd5, then try 11...Nf5. Finally, instead of 17...Nd5+, I have a mate in a few moves with 17...Nf5+

But Mr. Bullock learned his lesson and had his revenge:—

and the final game was conducted by 9 year old Sammy Reshevsky in 1920. I've included the notes from the American Chess Magazine.:—