Bobby Fischer And The King's Indian Defense

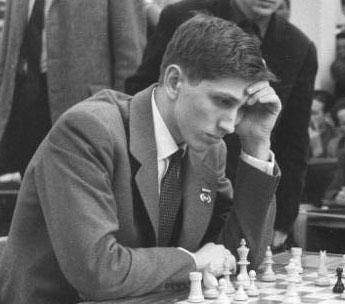

After Boris Spassky came the most famous chess player ever: Bobby Fischer.

Fischer was the world champion with the most limited and consistent opening repertoire. Indeed, Fischer had an attitude that there must be one correct way of playing in each position -- or perhaps more accurately, he felt that consistency was required to fully become expert in a variation, and that a chess player should find "his" opening and stick with it.

Fischer fairly early on found "his" openings. He always played 1.e4 as White, and as Black he met 1.e4 with the Najdorf and played the King's Indian against all the closed openings.

While he varied on occasion, as a surprise weapon or against a particular opponent, he basically remained faithful to these openings as the backbone of his repertoire and his understanding of chess, from the beginning of his career until the end, even including his one-time comeback in 1992 against Spassky.

It is ironic that a player who invented "Fischer Random Chess" and bemoaned the ever-increasing amount of theory would be the same who was the biggest (until that time) specialist in certain openings, and the most dedicated and hardest worker on opening theory. One can surmise that the young Fischer did not view his work on his favorite openings as an unpleasant necessity in order to achieve competitive success.

Rather, I think that as a young player he genuinely enjoyed the opening theory. But over the course of years one's perspective can change, one might become tired of what one did with joy as a youth, and suddenly years later you have the bitter, older Fischer who felt that opening theory was killing chess.

Fischer is known for the clarity and directness of his play. Thus, it might seem that an extremely complex opening like the King's Indian would not suit him as well as one of the various classically-direct openings. But Fischer had reached an unprecedentedly high level of technique and understanding, and thus rather than being carried by the crazy winds of complications -- as most King's Indian players are -- he could control them himself.

The complexity only served to lead his opponents astray, not himself.

Thus, for instance, let us see Fischer's win against Jan Hein Donner, where the complicated, "twisted" kind of position arising from the fianchetto variation of the King's Indian results in a game of classical simplicity:

Fischer was consistent in his use of the King's Indian, and even within that opening he tended to respond in the same way to each of White's variations. For instance, he almost always met the classical main line (Nf3/Be2) with 6...e5, and if 7.0-0 then 6...Nc6. The resulting lines with attacks on opposite sides of the board are now the deepest theory in the King's Indian, but in the 1950s and 1960s, it was fairly new.

Indeed, Fischer's international career began only a few years after the Mar Del Plata 1953 tournament, which for the most part introduced the variation and provided its name. Thus Fischer did not play as many such games as a modern King's Indian specialist would encounter. White players tended to play 7.d5 instead, or 7.Be3, if they did reach this position.

Nevertheless, Fischer's blitz game with Kortschnoj in Herceg Novi showed that he fully understood and had put a great deal into these lines which not long after became critical.

The King's Indian was also featured in Fischer's 1971 match demolitions of Mark Taimanov and Bent Larsen.

But interestingly, Fischer avoided playing the King's Indian entirely against Tigran Petrosian in the next, candidates final match. In addition, he had tended to avoid the opening against "Iron Tigran" in earlier, tournament play. It seems that despite preferring consistency, Fischer could be pragmatic too -- and thus usually avoided playing the opening that fed Tigran's family.

Nevertheless, Fischer felt the King's Indian positions perfectly, and could rely on them to mow down weaker opposition.

Ultimately, Fischer's approach to opening theory was one of consistency, and this was how he lived life as well. The true artist has to specialize in one thing rather than being a dilettante in many. Thus he became one of the biggest experts in his openings, and has inspired all the specialists in the King's Indian that followed.