Almost a Champion

What of these years between M'Donnell and Staunton?

"...in England, George Walker, Frederick L. Slous, and H. W. Popert were probably the leading players in active play . . . Slous (B. 1801, D. 1892) was a player of much promise, who, according to Walker, would have proved a formidable rival to Staunton had not ill-health compelled him to abandon chess. Popert had played much with MacDonnell, and had a reputation for defensive play."

-HJR Murray, "BCM," Nov. 1908

"Mr. Slous' culminating period as a player seems to have been about the years 1835—40, when between the death of Mac Donnell and the rise of Staunton to the championship he shared with George Walker the primacy of English chess. The latter, writing in 1844, says (Preface to Chess Studies, p. xi.): 'Had Mr. Slous continued to practise chess, it is highly probable he would have held the ground now occupied by Mr. Staunton.'"

-Rev. William Wayte, "BCM," Sept. 1892

"The Championship of England"

"It is often a thankless task to be the successor of a great man [M'Donnell], and so in this case nobody seemed in a hurry to step into the vacant office. In England, Mr. Popert, a German by birth, was considered the best player.... In 1841 a young player, Howard Staunton, having encountered many English players with great success, challenged Mr. Popert to play a match, the winner of the first eleven games to be the victor. Mr. Popert accepted, and after one of the hardest and best-contested fights on record, Mr. Staunton won by the odd game. "

-"Chess Player's Chronicle" 1859

While the above statements indicate there were some conflicting ideas about who was the best player between M'Donnell and Staunton, they also indicate that the choices were Walker, Popert and Slous. [John Cochrane, possibly one of the strongest players of his time, lived primarily in India.] Murray seemed to have favored either Walker or Slous while Walker himself pointed toward Slous. Staunton picked Popert to play for what would be considered the title of Champion of England.

Recorded results tell us a lot, though perhaps not everything. But if we follow such results as our guide, then there is no question that the best player of that time was Frederick Lokes Slous.

While we know that in 1840-1 Staunton beat Herr Popert by the odd game out of 25, Slous had beaten Popert, in total, 6 times with no loses and one draw. By the same token, Slous' record against George Walker is 15 wins against 8 losses and 2 draws.

It seems reasonable by comparing results to assign the position of "best English player" 1835-1841 to Slous.

That possibility accepted, we might then ask who exactly was Frederick Lokes Slous.

And then things become tantalizing.

On March 9, 1802 Frederick Lokes Slous was born to Gideon Slous and Sophia Ann Lokes Slous who lived on Panton Street in Deptford. Gideon was a minature portrait painter who, in defiance to his Huguenot ancestors' eviction from France, changed his name from the original "Selous" to "Slous." To complicate things, some of his chidren changed their names back to Selous (yes, even our F. L Slous) and his grandchilren were a mix of "Slous" and"Selous".

Gideon and Sophia had four sons. Frederick Lokes was the oldest living son followed by the respected artist Henry Courtney Slous, then by the dramatist Angiolo Robson Selous. The fourth son, Bryant, apparently died as a child even before Frederick was born. They also had two daughters, Emma Sophia and Matilda Bonelli.

Frederick Lokes Slous was married three times. The first marriage was to Julia Mole in 1935 with whom he had a son, Edric who became an army surgeon serving in India. Julia died in 1840 at age 30. The second marriage was to Elizabeth Russell Clipperton in 1844. Elizabeth died in 1847 at age 24. During his first two marriages they lived at Crescent-place, Mornington-crescent. Finally he maried Ann Holgate Sherborn on June 13, 1848. Frederick's brother Angiolo married Emily Sherborn, Ann's sister. The couple built and settled in a house on Gloucester Rd. in Regent's Park which at that time, other than for the homes of Frederick and his two brother who lived on either side, was nothing but open fields and woods for miles. Frederick and Ann had three sons, Frederick who died as an infant, Frederick Courteney Selous, the famous adventurer upon whom the fictional Allan Quatermain was based, and Edmund Selous, a lawyer and highy regarded amateur ornithologist, as well as three daughters, Florence Selous, Annie Berryman Slous, and Sybil Jane Slous.

The "BCM," in January 1891 announced the death Frederick's brother, Henry Courteny, the painter, giving some of his connections to chess:

Mr. Henry Courtney Selous, a painter of no mean distinction, was not himself (so far as is known) a chess player, but was closely connected with three of the most eminent experts of the century. He was the brother of Mr. Frederick L. Slous (otherwise Selous), the Nestor of living past masters; the brother-in-law of William Bone, the problemist; and the father in-law of Mr. G. W. Medley. Mr. Selous died not long since at his son-in-law's country house in Devonshire, aged 88.

Although all chess journals call him Slous, Frederick who, among other things, was a published writer, gave his name as Selous

This book was first published in 1844. It was reprinted in 1881 as "Stray Leaves from the Scrap Book of an Awkward Man." Antiquarian bookseller, Garrett Scott wrote:

An entertaining miscellany of verse, sketches and fiction from this man of letters who was president of the London Stock Exchange and (for a time) one of England's best chess players. The verses here include an account in heroic couplets of a chess game by Gioachino Greco (the seventeen moves are given in the footnotes--the game appears to this inexpert cataloguer a variation on the Giuoco Piano), as well as bald prose account of two postal chess games played between 1847 and 1849. Slous ranges beyond chess over such subjects as glaciers, at least one proto-detective story, and a supernatural story (first published in 1860 in 'Once a Week') that involves a wager in a cribbage game against a fiend.

We have been favoured by Mr. Fredk. L. Slous with a copy of his work, Stray Leaves from the Scrape-Book of an Awkward Man, Reprinted in 1881 from the Edition of 1843, with Addition and Substractions by the Author. The book contains 203 pages of well-selected and highly-amusing matter; essays, poems, the game of Chess, "Long after Homer," a sparkling little game from the Calabrois versified and so lucidly written that the game may be played over without the aid of the footnotes where the moves are given, a game played through the medinm of the post in 1847—1849 by the anthor and Mr. Horwitz, on behalf of the London Chess Club, against Amsterdam, and won by London, &c., &c. We have passed a few delightful hours in perusing the miscellaneous matter which the "awkward man" so cleverly presents to us. Whoever has a little leisure ought to read Mr. Slous' Scrape-Book, and he will be well satisfied.

F. L. Slous also has his name, as Selous, attached to some published musical scores such as "Soldiers Song," shown below, and "Married and Single" along with his collaborator, the Swedish composer Hildegard Werner:

Frederick's wife, Ann, was also a published writer. Her book of poems, "Words without Music," was printed in 1912. She also used the name "Selous."

I regards to the name, the chess-playing artist, Rosario Aspa, had this to say in his reminiscenses printed in the "BCM" in 1897:

"My sketching used to take me for a few weeks every year to Wargraveon-Thames, where I had friends, and where I made the acquaintance of Mr. F. Slous, who at the time of my introduction to him was, I believe, past eighty years of age. He was, however, still strong and active, taking long runs on his tricycle, and, though declining to play chess, showing still the greatest possible interest in it. He had borne most of the burthen in the great match between London and Amsterdam, and he is well remembered in classical chess books as one of the champions and worthies of old. He had great literary ability; gave me his translation of Victor Hugo's Le Roi S'Amuse, his "Confessions of an awkward man," and other tales and poems. Among many stories, he told me how two of his friends were, once, staying at the house of a mutual acquaintance, and how one night they had a severe tussle at chess, which ended in a draw. It was summer time, the night sultry, the friends' bed-rooms led one into the other, and the door was open. As light broke in the morning, one of them called out ''I say, are you awake?" "Yes indeed" came the answer, "With this confounded heat I cannot sleep a wink." ''Do you remember," began the other again, "How we left off? And, if you do, cannot you see that I was too hasty in consenting to a draw; could in fact by—(naming some moves) have won?" "I can remember the position very well" replied his friend, "and in answer to your new moves can see better play than that you allow. Let us go to the drawing room and try the thing on the board—no one is about." And down they went accordingly, in their night shirts. The sequel may be guessed; they tried every variation of every move, and they tried back, and they utterly forgot how the time had gone until they were roused by the screams of a housemaid, who, coming in to pull up the blinds, took them for ghosts.

Slous also told me stories of the intolerable slowness in play of some of the celebrated men of his prime—Popert, Perigal, and others; how he used to provide himself with something to read or to write while they were pondering their moves.

I had many games with Mr. Edmund Slous, a younger son, who bid fair with practice to equal his redoubtable father. He took "Pawn and two." Perhaps he could now give me these odds. In this family there is an amusing freedom in the way the different members spell their patronymic. This gentleman and his famous brother, the great African sportsman, spell it "Selous." So did an uncle, a fine artist of his day; while another uncle adopted another version—Sluys—if I remember right."

The eldest brother, my great-grandfather, and father of F. C. Selous, eventually when he retired in 1865 [this date seems wrong] had become Chairman of the Stock Exchange and had been, in quite large measure, responsible for the ending of the Crimean War as he had managed to stop a Russian loan being raised on the Stock Exchange and the war ceased shortly afterwards — the Russian Treasury being empty.

[The British goverment did, indeed, float two loans to Russia of 50 million roubles each, one in 1854 and one in 1855. And the London Stock Exchange board did, in fact, pass a resolution in Dec. 1855 that "they would not, after the restoration of peace, recognize any loan raised by a foreign Power when at war with Great Britain."]Fluent in Italian and French, as well as in English and tolerable (his own words) in Latin, Slous published translations of Victor Hugo's works, such as "Le Roi S'Amuse," "Notre-Dame de Paris" and "Les Miserables."

As a child, Slous was mostly home-schooled though he did attend private school for a short time. His recollection was that he could read at 3 and by the age of 4 was reciting Shakespeare. When in school, his teacher complained to his mother that Frederick couldn't even be put in the reading class for older children since he would embarrass them.

As an adult, Slous was considered a kind, charitable and responsible man who not only supported for his wife and children, but also for his parents. In his later life, Slous became visually impaired.

Although he apparently could play chess from at least his teens, Frederick Lokes Slous was highly active as a first-class chess-player from around 1835 until about 1841. He is said by some to have temporarlily retired from chess at that time but Walker claimed he gave up serious chess due to ill health. Walker also claimed that Slous, along with Wellinton Pullling and William Bone, was capable of playing sans voir - a rare thing in those days.

Augustus Mongredien said this about Slous:

A very able player, who rapidly rose to a high rank, and might have risen to the highest, had he continued his Chess career; but he soon abandoned the practice of the game, and contented himself with becoming a spectator and critic of other players' exploits. His actual play was chiefly with McDonnell, G. Walker, Popert, and their contemporaries, but his interest in the game extends, I believe, up to the present era [1882].

Howard Staunton, in "The Illustrated London News" on May 26, 1866, upon the death of Wellinton Pulling, wrote:

"The most rapid, and at the same time the most brilliant, English player of the last thirty years was Mr. Wellington Pulling, whose death. recently, will be regretted by all who knew him."

However, in 1836 Slous had played Pulling 2 games giving him the odds of an exta move in both games and winning both games. Here is one of those games:When Slous resumed serious chess in 1847, he was completely out of practice. Harrwitz had just returned to England and played a great number of games with Slous. Slous had extrememly poor results winning 11 but losing 27 and drawing 6. Staunton claimed that most of Slous' wins were at the end of the series, indicating he was regaining his form:

"In reference to this fine collection of Games now nearly brought to a close, we think it right in justice to Mr. S—s, who appears as a considerable loser on the balance, to state that the greater part of them were played by him after many years total cessation from Chess practice, and, that of the latter ones, when he had somewhat regained his former strength, he won a majority, and fully established his claim to be considered at least as powerful a player as his ready and well practised antagonist." - "Chess Player's Chronicle," 1848

However, in 1853 Slous and Harrwitz contested a dozen (recorded) games and Harritz dominated Slous' with 10 wins and only 2 loses, indicating that Slous had had his half-decade in the sun and his time had come and gone.

We are left with very few examples of Slous' play after his encounter with Harrwitz. One notable exception is his inclusion as one of Morphy's 8 opponents in his blindfold exhibition at the London Chess Club on April 13, 1859. In this match Morphy's other opponents were George Walker, F. E. Greenaway, F. G. Janssens, Augustus Mongredian, George Webb Medley, G. Maude and J. P. Jones. Due to the lateness of the hour all but 3 games were abandonned. Slous' game was one of these, but Slous did have a one pawn advantage at that time:

In 1836 Slous played Capt. Evans, of the Evans Gambit fame, 6 games, winning all 6. Below is one of those games.

Here is but one of Slous' many wins over Walker:

Slous had a +5-2=3 score against Jószef Szén (compared to Walker's negative score against Szén). Below is one of Slous' victories.

In July of 1884 the "BCM" published the following:

It is not often that a writer survives to witness the deserved republication of an early work sixty-five years after its composition and more than sixty after its first appearance. Such is the happy fate of Mr. Frederick L. Slous, the author of the following poem, who still enjoys a ripe and vigorous old age. It was written in 1819 or 20, when the author was a lad in his teens, and first published in pamphlet form in 1823. Since then it has been reprinted in the Chess Player's Chronicle for 1844, a work which has long ceased to be accessible, and more recently in a collection of fugitive pieces by the same writer, printed for private distribution only, of which we have been favoured with a copy. The younger generation may require to be informed that Mr. Slous was one of the very finest players of his time, in the days of the Old Westminster Chess Club before the advent of Staunton, and was within reach of the highest honours of British amateurship, when he was compelled by ill health—happily only temporary—to retire. Very few of our readers, we are convinced, can have seen this admirable specimen of vers de societi; all, we feel sure, will appreciate its merits, which need none of the apologies usually tendered on behalf of juvenile compositions, and will join us in congratulating the venerable author and wishing him many more years of life's bright sunset.

We print first the moves of the game embodied in the poem which follows. It will be seen, on comparing them in detail with their versified description, how closely and correctly they are depicted. The game itself is one of Greco's "racy morsels."

Arms, and the Game I sing, whose varied maze

The subtle arts of warring hosts displays;

O'er which nor Jove nor Juno's self presides,

Nor chance directs, nor erring Fortune guides—

But skill alone the pensive strife decides!

Behold the Board in ready order plac'd,

With eight-times eight alternate chequers grac'd!

First at his post the milk-white King is seen,

Of form gigantic, and imperious mien;

With haughty step, that shakes the solid ground,

One square he moves on every side around,

From death secure !—for, by the laws of Chess,

Whichever side, amidst the fighting press,

Can hold in galling bonds the royal prey,

The laurel wears, and wins the desperate day!

Thus as he moves, the deadly contest turns;

Grim carnage there with thirst unsated burns;

To foil each snare his loyal subjects spring,

And die with joy to save their fated King.

Beside him fierce the warrior Queen appears,

Inured to combat from her earliest years:

Her left arm bears a shield, her right on high

Waves the dire axe, and points to victory.

At one fell bound she clears the spacious plain;

Pale Death and Horror follow in her train.

On either side, expectant of the fight,

The mitred Bishops range to left and right:

Not like the sleek-poll'd race of modern dates,

Who wage no war except with well-filled plates;

But fierce, revengeful, turbulent, and bold,

Whose arms drop blood, as Beauvais' did of old. *

With course oblique they seek their thoughtless foes,

And from afar direct insidious blows.

Next the bold Knights their fiery coursers guide

With headlong speed through war's empurpled tide;

Alert and brave they spring amidst the fight,

From white to black, from black to candid white.

Last, on each flank, the ponderous Rooks appear,

Each wing defend, and guard the helpless rear;

Direct they move, and sidelong from afar,

Stern towers of strength and thunderbolts of war.

Before each Chief a trusty Pawn attends,

Whose knotted spear the close-wedged front defends;

Sworn to prefer, amidst the dangerous fight,

Impending death to base inglorious flight!

Onward they move, yet aim no honest blow,

But strike obliquely at the passing foe.

In equal ranks the sable warriors stand,

And call for war, impatient of command.

First to the fight the white imperial Pawn

Two paces strides across the chequered lawn;

With equal haste, inspired with equal rage,

The swarthy Pion rushes to engage;

In middle space th' opposing heroes frown'd,

Prepared to strike, yet impotent to wound.

On different sides the hostile Knights advance,

Shake their keen brands, and couch their beamy lance;

Tasgar the fierce, and Asdrubal the strong,

Whose deeds transcend the feeble powers of song.

Next from afar, with bold impetuous spring,

The martial Bishops rush from wing to wing;

Well skilled in death, the pointed dart they throw,

Yet sometimes close and grapple with the foe.

Roland the brave, the candid chieftain's name,

The black, Argante, high enroll'd in fame.

With cautious step, behind his ample shield,

The Bishop's Pawn moves onward to the field;

When, from the swarthy ranks, with fiery haste,

The Black King's Knight, indignant Orcan, pass'd.

O'er all the field he casts his angry eyes,

At length the royal Pawn forlorn he spies,

And aims a blow,—meanwhile, for danger rife,

The White Queen's Pawn leaps forth amid the strife.

Incautious youth! by one descending blow

He sinks in blood before his sable foe!

Beneath his throat the thirsty weapon glides,

And breath and life at one fell thrust divides;

Ponderous he falls—his clanging arms resound—

And terror chills each beating heart around.

Revenge! revenge! the swarthy victor bleeds!

Grim-visaged Death arrests his gallant deeds,

For as to spoil the panting chief he press'd,

The Bishop's Pawn transpierced his eager breast,

Convulsed he falls—with glances that deride,

Th' insulting foe beheld him as he died;

Then leaped exulting where supine he lay,

And hurl'd in air the gory corse away.

With daring hate, beside the sheltering wing,

The gloomy Bishop threats the candid King.

A Knight there stood, as yet unknown to fame,

Beauteous as morn, and Mildar was his name;

With loyal wish his sacred King to screen,

Prepared for death, he bravely springs between.

Ah, hapless youth! by ruthless fate decreed

Before thy monarch's pitying eyes to bleed!

The star-crown'd Gods, who sit enthroned above,

In awful guise around Olympian Jove,

Who gaze on war amongst us mortal elves,

With cheek unblenched (being snug and safe themselves)

E'en they, unasked, from Heaven's unclouded sphere

Had dropp'd one soft commiserating tear;

And now abandoned, 'midst the gory plain,

The royal Pion dies, by Orcan slain.

Behind the ranks, the King retires from sight,

The watchful Book protects him in his flight.

Inflamed with rage that yet unsated burns,

The swarthy Knight to youthful Mildar turns;

Full on his chest the ponderous steel descends,

And through his helm a struggling passage rends;

His crashing skull the griding stroke divides,

And to the throat with force resistless glides,

Whilst from their hollow seats pressed forth and crush'd,

The bleeding eyes with brains commingled rush'd.

Fired at the sight, his trusty Pion stood,

And marked with swelling breast his master's blood;

Then onward rush'd, and as the foe drew near,

Above his hip he drove his fatal spear.

Without a groan, the swarthy hero fell,

Content in death to be revenged so well.

With certain aim upon the blood-stained heath,

The Black King's Bishop wields the pointed death:

Pierced through the throat, the faithful Pion dies;

Beside his master's corse supine he lies.

Now fiercely springing to her Knight's third square,

The warrior Queen renews the fainting war;

Each hero's soul her martial ardour fires—

Her taunts inflame—her generous praise inspires.

Still his dire course the gloomy Bishop held,

By gathering hosts around him unrepelled;

He marked, where towering at his station stood,

The White Queen's Book, as yet unstained with blood,

He marked and slew; with one resistless blow

He strikes to earth his unsuspecting foe.

Now lightly springing o'er the spacious lawn,

The White King's Bishop slays a faithful Pawn.

Awed at the sight the dusky King retires,

Laments his fate, yet still the deed admires.

The White Queen's Bishop seeks the gathering war,

And threats his sable consort from afar;

But swiftly summon'd from the dusty field,

Her Knight presents his interposing shield:

Impetuous Tasgar joins the attacking force,

And nimbly leaps, with well-directed course,

To where the Royal Pion once had stood,

Now pale in death, and stiff with frozen blood.

The Black Queen's Pawn moves on in hopes, unseen,

To shut the Bishop from his guarding Queen;

But vain the attempt! the watchful Queen attends,

Sidelong she springs, and still the piece defends.

The Black Queen's Bishop darts between the foes,

Again perchance the captive to enclose;

But warned before, the cautious foe retires,

And on the intruder turns his angry fires.

Its aiding spear the Black Knight's Pawn extends,

And the brave Bishop from the stroke defends.

Ill-judged defence! at one infuriate spring,

The vengeful Bishop threats the helpless King;

In vain from check with trembling steps he flies,

In vain for help sends unavailing cries;

The White King's Bishop seals his hapless fate,

And all is ruin, horror, and Check-mate!

* When this very Christian prelate was taken in battle by Richard I of England, the Pope applied for his release; claiming him as his son —— , upon which the jovial monarch sent him the Bishop's coat of mail, besmeared with blood, and this pithy scriptural quotation:—— " This have we found; know now whether it be thy son's coat, or no." —— F. L. S.

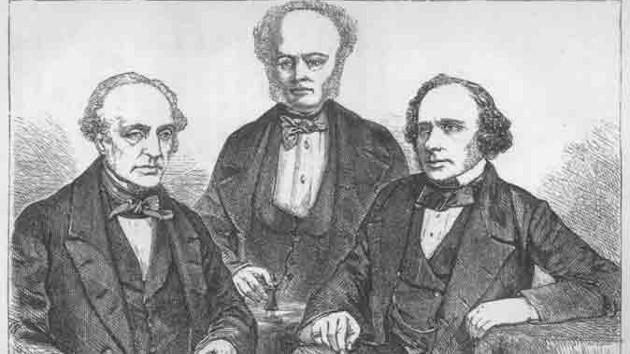

The thumbnail/cover image which shows, left to right, Willam Lewis, George Walker and Augustus Mongredien was originally plublished in Frederick Milne Edge's book, "The Exploits & Triumphs in Europe of Paul Morphy."