A Quiet Game in Germantown in 1762

Harbeson's story is pure fabrication, carefully contrived using known facts to connect the people involved and provide a backdrop for the presentation of two artifacts, the chess sets once owned by Bartram and Franklin.

Today both sets of artifacts are in the possession of the American Philosophical Society.

Images of the sets at the APS can be seen here: Franklin Bartram

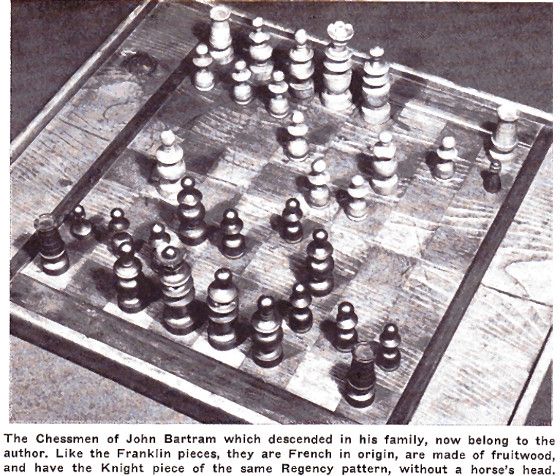

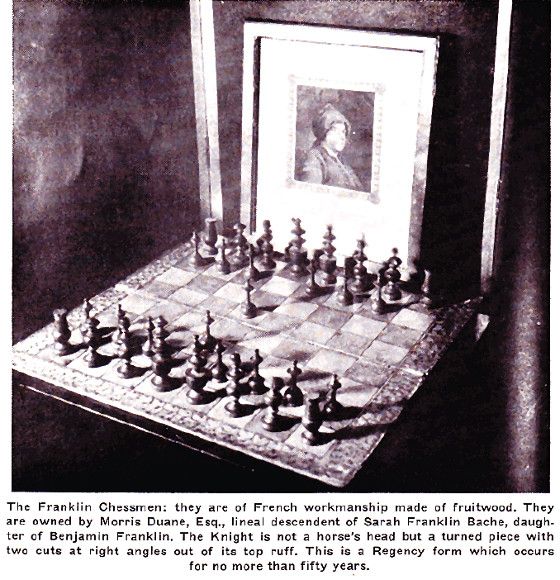

The images of the chess sets below are from Harbeson's article.

Both sets are of the early Regency style, named for the Café de la Régence of which Diderot wrote: "Paris is the place in the world, and the Café de la Régence the place in Paris where this game is played best."

One of the most noticeable differences between the early and later Regency styles is the Knight. In the old, less expensive style, the Knight is a turned piece rather than a carved horse's head. It's size and the slits in it's cap sets it apart from the other pieces. Denis Diderot inserted an engraving of this style set in the "Encyclopedie de D'Alembert et Diderot."

A Century-old Photograph of Franklin's Chess Set.

Before reading the story, it may be well to note that the game used by the author is actually one played between James Thompson (White) and Paul Morphy (Black). It was their first game played during the 1857 Congress in New York and the first one given by Willard Fiske in the Congress Book.

Also, Harbeson made an small but peculiar error. William Rittenhouse, one of the first American paper makers, died before Franklin was two years old. His business was handed down but his children were named Nicolas (grandfather of David Rittenhouse), Gerhardt and Elizabeth - none of his descendants during Franklin's time were named William. So, although Franklin did, in fact, do business with the Rittenhouse Paper Mill, the appearance of it's founder, William Rittenhouse, in the story is clearly impossible.

Peter Collinson of London, the botanist and Fellow of the Royal Society also mentioned in the story, was indeed a dear, though distant, friend of John Bartram and a frequent correspondent with Franklin.

The story mentions Philip Stamma's chess book. On Sept. 20th, 1751 Franklin wrote to his bookseller, William Strahan, "There is a little book on the game of chess, by Philip Stamona [sic], printed for J. Brindley, 1745 ; if to be had, please to send it to me, with the remaining volumes of Viner as fast as they are published." But then on June 20, 1753, he wrote Strahan, "Honest David Martin, Rector of our Academy, my principal Antagonist at Chess, is dead, and the few remaining Players here are very indifferent, so that I have now no need of Stamma’s 12/ pamphlet, and am glad you did not send it." Whether Franklin ever re-ordered the book is unclear but the 1813 catalogue for the Library Company of Philadelphia does not list Stamma's book

Other than the postscript, everything below, although reformatted, comes from Harbeson's article.

A Quiet Game in Germantown in 1762

by John Harbeson

It was a pleasant afternoon in early summer. Benjamin Franklin, printer, had just come out to Germantown to order his next year's supply of paper from the Rittenhouse Paper Mill on Crab Creek [1] in the Wissahickon Valley, and had been accompanied by William Rittenhouse to his home nearby.

"For," said William, "my cousin David the astronomer, a good friend of yours, is coming out for supper, and I would be happy to have you join us. He has been working on an orrery and would, I feel sure, appreciate your opinion of its mechanics."

"Yes, he spoke of it at last weeks meeting of the Philosophical Society," said Benjamin, "and I told him of a form of ratchet I saw used in London. I have a notation of it in my pocket, I will come with pleasure."

When they arrived at the house, [2] David was already there.

"Ah, Benjamin, I am glad to see thee, and look who I saw on the way up the valley and brought with me! John Bartram was digging up young shoot and putting them in his basket. He says they are plants of possible use in medicine abroad and had promised to send them to your friend Peter Collinson in London. As his basket was already full he was more readily persuaded."

"John Bartram, old friend, I am indeed happy to meet thee. For the chessmen I ordered for thee on my recent journey to London have now come. [3] They are like my own, of the French pattern, of pearwood and very playable. And you know how much I like to play chess."

It is ever a way to waste time," broke in David, "time which for my part I feel better used in mathematical study. I am working on the computation of the transit of Venus which will occur in a few years and fear I shall not complete all the mathematics in time to have my telescope pointed in the right corner of the heaven."

If I could help you in your calculations, I would," said Benjamin, "but indeed I have not the skill. And so I shall continue to play chess. For chess is not merely an idle amusement; several very valuable qualities of the mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired and strengthened by it ; for life is a kind of chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and ill events that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or of the want of it. And this we may learn by playing at chess." [4]

"Ah," said William, "there will be time before supper for you to play a game with John. I have the pieces set up, by the window."

"And I," said David, "as I could not keep my mind on astral matters, will keep an account of the moves, for my father taught me the notation."

It was not a brilliant game, [5] as such games go. Benjamin, having the move, advanced his King Pawn two squares, and John then did the same. It became a Giuoco Piano opening, of which the first moves had been given, with explanations, in the "Noble Game of Chess," published by Philip Stamma in London in 1745, of which a copy was on the shelves of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

At this point, seeing himself at fault, Benjamin composedly taking his King from the board, he put him in his pocket. John Bartram looked up. The face of Franklin was so grave, and his gestures so much in earnest that John began with an expostulary,

"Sir!"

"Yes, good John, said Franklin, "continue— we shall see the party without a King will win the game." [6]

IN fact the game was over. Bartram's mind, almost as good at chess as it was at exploring the plant world, had worsted Benjamin Franklin, a better philosopher than a chess player, and more intent on the symbolic connotations of the game than its rational development, He lost with good grace. And William had carried in a decanter of old Madeira and lighted the candles.

"We are having dinner early so David can drive you back to town."

The evening passed quickly, the conversation between these life-long friends on a very lofty plane.

"We must meet again soon," said Benjamin— "perhaps I can give you better competition."

But this was not to be, for Franklin was soon after again sent to London by the Pennsylvania Assembly to interest Parliament in its quarrel with the Penn Proprietors. And from then on his chess playing was in London, and in Paris, and at Passy.

Story by Courtesy of "The Germantowne Crier"

1. The first paper mill in Pennsylvania was built in 1690 by William Ryttenhuisen, now anglicized as Rittenhouse, recently come from Holland, in the valley of the Wissahickon on Crab Creek. It stood about 100 yards higher up the stream than the Rittenhouse house. The mill remained in possession of the Rittenhouse family until 1811. ["Jackson Encyclopedia of Philadelphia," Vol. IV, p. 964.]

2. The birthplace of David Rittenhouse in "Rittenhousetown" on what is now called Lincoln Drive was built by his grandfather. David's parents moved to a farm in Norristown. There from his teens David made clocks of wood and metal. David Rittenhouse, astronomer, philosopher, mathematician, first Director of the Mint, was born in 1732, died 1796. [op.cit. Vol. IV, p. 1047]

3. In Volume 55 of the "Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography," page 106 is "an account of my (Benjamin Franklin's) voyage to England, Disbursements, etc. 1757

Dec. 3 Paid for chessboard and men 7.0

" coachhire to Neats

" and back 4.0

" to billy 4.0

" to billy 10.6

" to billy 4.6

4. These ideas were expressed in Franklin's "Bagatelle" called "The Morals of Chess" which first appeared in the Dec. 1786 issue of the "Columbian Magazine," printed in Philadelphia. It was translated into many languages—including Russian—and was printed in many chessbooks of the early 19th century.

5. For this game see "The Book of the First American Chess Congress" by Daniel Willard Fiske, published in New York, 1859, p. 127.

6. From a letter written by Lafayette, describing a game of chess played by Franklin as the Cafe de la Regence in Paris, cited in Smyth and in the "Folder of the Good Companion Chess Problem Club."

Postscript:

One will notice, looking at the Bartam set that the h1/a8 squares are black. This issue was brought up by a John Overall, a reader of "Chess Review." John Harbeson, considered an authority on chess sets by the editors, replied:

John Overall's letter is deserving of an answer. John Bartram was born in 1699, died in 1777. He did not belong to a chess club, had access to practically no book. The first chess book published in America — "Chess Made Easy" was issued in Philadelphia in 1802. In the photograph published in "Chess Review" for January '62, page 19 shows the pieces as they were set up by Bartram. He was quite happy with this board, made in New England about 1760; the squares are in reality all practically the same color; the alternate squares are set off by reversing the grain of the wood. In some lights the squares with more pronounced grain look lighter.

But Mr. Overall should remember that America was an outpost in those days. And if he will look through H.J.R. Murray;s "A History of Chess" he would glean these facts:

Before chess came to Europe the board was "unchequered"— i.e. was of one color, the squares set off by lines only. At about 1000 A.D. (four centuries after the game is first mentioned in literature) it became usual in Europe to use a chequered or parti-colored board. This is no necessity of the game,but it simplifies the calculation of moves and is a ready means for preventing the occurrence of false moves. Once the use of the colored squares became general it was possible to frame rules to govern the position of the board when place for play.

The diagrams in Alphonso X manuscripts (1283) have invariably a white square to the player's right hand side, but the other problem manuscripts which are to be found in early illuminated manuscripts show there was no uniformity of practice. The modern convention or rule that each player must have a white square at his right-hand corner was not established during the medieval period.

Looking through Philadelphia newspapers of Colonial times indicates that many of the conventions of polite life were dispensed with.