50 Years Later: Why Fischer Vs. Spassky Was The Greatest World Championship Match

Chess has a long tradition of matches for the highest crown. Even after 50 years, perhaps the Match of the Century still reigns supreme as the greatest competition between a challenger and a defending champion. My reflection on the World Chess Championship 1972 between GM Bobby Fischer and GM Boris Spassky may explain why.

Soviet superiority in the chess world had been the norm since GM Mikhail Botvinnik won the title in 1948—the champions and challengers for the world championship from 1948 until the 1972 match were solely Soviet grandmasters. Although his first Candidates debut was in 1956, Spassky's career slowed down a bit until he tied for first in the 1964 Interzonal tournament. This performance eventually allowed him to challenge GM Tigran Petrosian for the title in 1966.

Spassky was probably already the strongest player in the world in 1966. Decades later he confided to me: “At that time I was so strong that nobody could stop me.” Nobody, except for Petrosian, but that was only a temporary matter.

While GM Vasily Smyslov won two Candidates tournaments, Spassky's record was even more impressive. In 1965 the Candidates tournament was replaced by matches, and Spassky won six matches in two cycles. He was an all-around player with a strong sense of initiative.

At that time I was so strong that nobody could stop me.

—Boris Spassky

- After World War II

- Soviet Hegemony

- Decisions By Fischer

- Goal Of World Championship Match

- Setting Of Cold War

- Analysis Of Each Player

- Fischer Or Spassky As Favorite

- Selection of Reykjavik

- Match Gets Underway

- Fewer Mistakes

- Effect Of Championship Match

After World War II

In the post-World War II era, nine matches were held until 1969, all of them in Moscow between Soviet players. It was a routine that the chess world had become accustomed to. A change was about to come, however. In 1970 a match on 10 boards was held in Belgrade between the Soviet Union and the "Rest of the World." In the 1950s and early 1960s, such a match would have created little interest; the Soviet Union would have won convincingly. This time they managed only the narrowest of victories. The world outside the Soviet Union had become stronger.

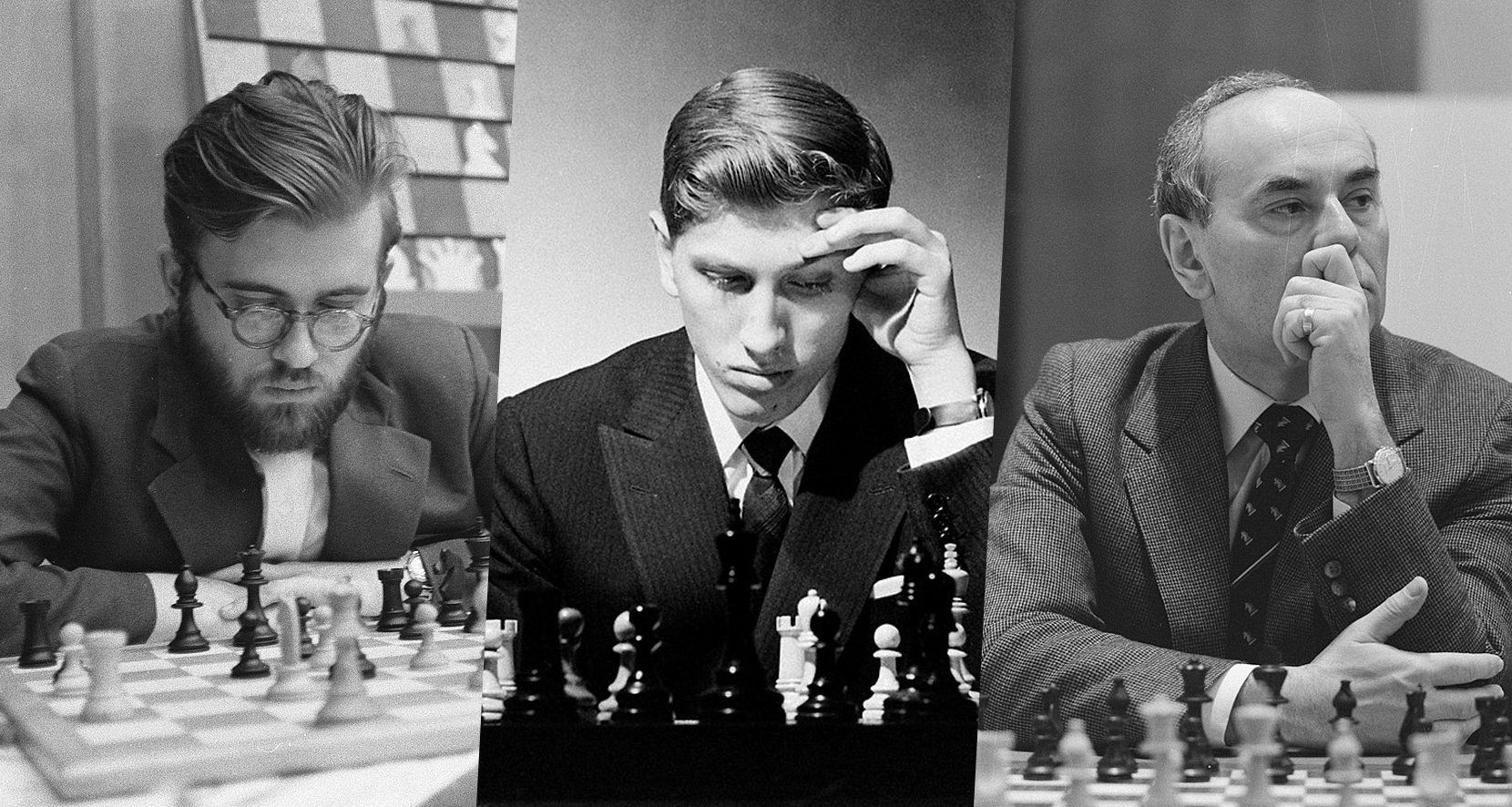

The first three boards of the “Rest”—GMs Bent Larsen, Fischer, and Lajos Portisch—all won their mini-matches against Spassky, Petrosian, and GM Viktor Korchnoi respectively. As a result, were they a threat to the Soviet hegemony? Portisch was certainly a very strong grandmaster. His positional style earned him the nickname “The Hungarian Botvinnik.” He qualified for the 1965 Candidates matches, in which he lost to GM Mikhail Tal.

In the next cycle, Portisch narrowly lost to Larsen, who was at his peak in the second half of the 1960s. The great Dane won many tournaments in these years. After his win against Portisch, he was, in turn, eliminated by the future champion, Spassky. It is clear that the Soviets were not really afraid of Larsen and Portisch; their main worry was Fischer.

Soviet Hegemony

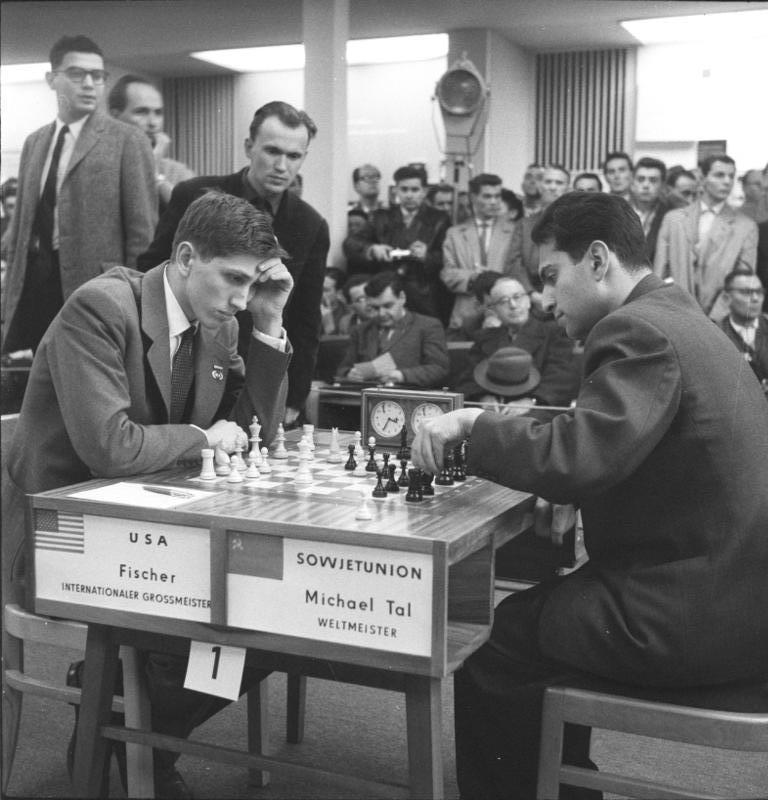

In 1962 Fischer won the Stockholm Interzonal with a tremendous score, 2.5 points ahead of his Soviet contenders. He was then just 18 years old. The result must have scared the Soviets: after 14 years their hegemony was threatened in an unprecedented way. Fischer's time had not yet come, though. In the famous Curacao Candidates, he didn't play any role of importance.

Three Soviet players dominated the event: Petrosian, GM Paul Keres, and GM Efim Geller. It was a bitter disappointment for Fischer who later claimed that the top three contenders had made pre-arranged draws against each other. He was right but that didn't change the situation: Soviet hegemony was guaranteed for another three years.

Fischer's failure in Curacao changed his attitude towards the FIDE cycle. He had experienced that a great victory in the Interzonal was no guarantee of success in the Candidates. He didn't play the Interzonal in 1964 in Amsterdam. Instead, he made two attempts to arrange a match between himself and the world champion—to no avail. In fact, there was no chance at all that the Soviet Chess Federation would be ready to accept such a challenge; they cherished their world title.

Decisions By Fischer

Fischer decided to play the next Interzonal in Sousse, Tunisia, but after winning one game after another he withdrew due to difficulties with the organizers. He seemed disillusioned. In 1968 Fischer played—and won—two tournaments, and then he withdrew from practical chess.

Right before his second match against Spassky, Petrosian came up with a remarkable statement: he asserted that Fischer didn't want to play Candidates matches out of fear of losing. It was an interesting view: both Larsen and Portisch had lost to a Russian top gun on their way to the highest throne. Would Fischer have been able to hold his own against Spassky in 1968? He would certainly not have been the favorite.

It is difficult to determine why Fischer made certain decisions in his career. There is a curious antithesis: Fischer operated very efficiently behind the board, but in real life, he was very insecure. In hindsight, you could say that he was right by getting involved in the world championship cycle at a relatively old age—he avoided any defeat this way.

Petrosian's assertions may have triggered Fischer to come back to chess in 1970. He accepted the invitation to participate in the Soviet Union vs. The Rest match in which he defeated Petrosian 3-1. An astounding result! Subsequently, during the prize ceremony, Rosser Reeves of the U.S. Chess Federation proposed to organize a match between Spassky and Fischer. That had been Fischer's dream idea many years earlier. Spassky reacted politely but turned it down; he knew that the Soviet Chess Federation wouldn't allow such a match.

Incidentally, Fischer had agreed to play GM Mikhail Botvinnik in an 18-game match in Leiden, the Netherlands, later that year. Everything seemed set for this most interesting clash when Fischer came with a new demand: the format had to be changed; the winner should be determined by six wins, draws not counting. In fact, this was a very old idea; the match between Alexander Alekhine and Jose Capablanca had this format. The organizers couldn't handle it for obvious reasons, and the match was canceled.

Goal Of World Championship Match

Possibly Fischer lost his interest in the match against Botvinnik because he had set himself a higher goal: a world championship match against Spassky. Fischer decided to play the Interzonal in Palma de Mallorca. He won again, this time with a 3.5-point lead. Subsequently, he beat both GM Mark Taimanov and Larsen 6-0 in the Candidates. That was absolutely unique in chess history.

After his match with Larsen, Fischer appeared on the Dick Cavett Show where he said one of his most famous quotes: "The greatest pleasure [in chess]? When you break his ego."

Now the real struggle against the Soviet chess empire lay ahead: he faced Petrosian and, if he could overcome him, Spassky. In ancient Greek tragedies, the lone hero arrives, ready for enormous tasks. Fischer was a modern version of such a hero.

Though chess was not very popular yet, Fischer's heroic acts didn't go unnoticed. He received a personal letter from U.S. President Richard Nixon who wrote: “I wanted to add my personal congratulations to the many you have already received. Your string of 19 consecutive victories in world chess competition is unprecedented, and you have every reason to take great satisfaction in your superb achievement. As you prepare to meet the winner of the Petrosian-Korchnoi match, you may be certain that your fellow citizens will be cheering you on. Good luck!”

Your string of 19 consecutive victories in world chess competition is unprecedented.

—U.S. President Richard Nixon, in letter to Bobby Fischer

It is significant that Nixon—or possibly one of his aides who wrote the letter—knew the ins and outs of developments in the world championship cycle.

The match against Petrosian took place in Buenos Aires. Fischer experienced his first difficulties in the cycle: in the first three games he was lost, and he would be satisfied to score 1.5 points. After five games, the match score was still equal. I remember that I, as a fervent Fischer fan, was worried then. How on earth could he beat Petrosian, the past master of strategy and defense? The worries didn't last long. Fischer got into his stride and won the last four games. He was ready for the great match.

In an interview, Spassky came up with a polite reaction: “I must say in all sincerity that Fischer performed splendidly. His play leaves a very good, pleasant impression.” It is not clear whether the world champion was greatly worried about the upcoming match. In Buenos Aires, Fischer's play had not been consistent.

Setting Of Cold War

Fischer's triumph was hailed with great enthusiasm all over the world. He received another personal letter from Nixon who wrote: “Your victory at Buenos Aires brings you one step closer to that world title that you so richly deserve, and I want you to know that together with thousands of chess players across America, I will be rooting for you when you meet Boris Spassky next year.”

It was the time of the Cold War. The fight between Spassky and Fischer could easily be seen as a personification of the fight between the two superpowers. While the chess community was mainly interested in the moves on the board, the outside world looked at the machinations and the intrigue. And that was all around. Fischer's most famous comment is: “Chess is war over the board. The object is to crush the opponent's mind.”

Chess is war over the board.

—Bobby Fischer

Yes, chess was certainly an apt metaphor for the Cold War. Fischer didn't mince his words when he explained that he was the best player in the world and that he would prove it: “The Russians have held my title for ten years, and they're going to be in for it when I win the championship. They're going to have to wait and play under my conditions.”

Analysis Of Each Player

Fischer was brimming with confidence, and the Soviets had been worried ever since Fischer decided to play the Interzonal. The Soviet Chess Federation held regular meetings with all top players to discuss the phenomenon of Fischer. The main topic was: how could he be stopped? Before the match against Petrosian, a group of four distinguished grandmasters, Isaac Boleslavsky, Lev Polugaevsky, Leonid Shamkovich, and Evgeni Vasiukov, prepared a confidential report, which was an analysis of Fischer's play.

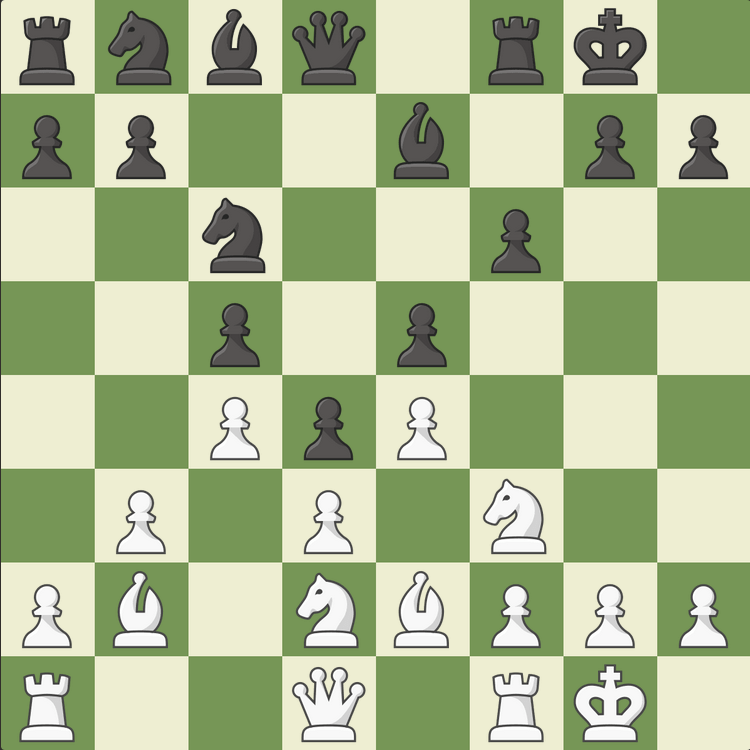

This 30-page document entitled The Conclusions of a Special Methodological Meeting contains theoretical opening research in a systematic way and a summary of Fischer's play in general. One conclusion strikes me especially: the distinguished grandmasters wrote: “Fischer is not very confident in closed positions, which he accordingly tends to avoid. In maneuvers—in positions with a locked center—Spassky and Petrosian seem to be superior to him.”

The first part of the conclusion is right: in both matches between Fischer and the Soviet champions, few games with a closed character were played. But when they did appear on the board like in the sixth game, Petrosian-Fischer, and the fifth game, Spassky-Fischer, the American won in a convincing way. This illustrates how difficult it is to speculate about general aspects of a top player's style.

More important are the conclusions about openings. The Soviet research was very professional and thorough. Before the big match, the preparation intensified. Tal, Petrosian, Keres, and Smyslov all wrote long confidential letters, reflecting in-depth on Fischer's play. The theoretical work by this large group of Soviet top players pales in comparison with today's computer preparation, but for those days it was extraordinary. In contrast, Fischer almost always worked alone on openings.

In 1970 Fischer received a collection of index cards from English IM Bob Wade that contained a systematic account of what his opponents in the Interzonal had played. The cards were handwritten by young English players. Wade also later prepared two loose-leaf books on Spassky's openings.

Besides, not long before his match against Spassky, Fischer obtained the 27th issue of the German series Weltgeschichte des Schachs that contains 355 of Spassky's games. It was certainly not a complete collection of Spassky's games, since he had played over 1,000 serious games by that time. Still, it was a most valuable book for Fischer who took it with him all the time and wrote his own notes in it. The advantage of working alone is that you are very well aware of what you're doing. Spassky had to study the findings of others.

Fischer Or Spassky As Favorite

Who was the favorite? At the time I had no doubt that Fischer would win and was surprised to learn that not everyone thought the same. A number of top players had Spassky as their favorite. In hindsight, I can understand this view. Spassky had much more match experience than Fischer. In a period of five years, he had beaten Keres, Geller (twice), Tal, Larsen, Korchnoi, and Petrosian in matches—in most cases with an impressive score.

Apart from that, Spassky had a very positive score against Fischer: three wins with two draws and no losses. The significance of such a lead is not necessarily an advantage; Nepomniachtchi had a similar plus score against Carlsen last year but was soundly beaten. And if we go back in history, Capablanca had beaten Alekhine five times with seven draws prior to their world championship match. Alekhine inflicted him with a loss in the very first game!

I believe that Fischer had one clear advantage: he had played challenging matches in 1971 that had given him a lot of confidence. Spassky, on the other hand, had restricted himself to tournament play that didn't seem to inspire him. His play had been lackluster, and he lacked recent success.

I awaited the match with trepidation. Moscow would not be the battleground for the first time in the post-war era. Many cities were possible candidate venues, and it was not easy to get Fischer and the Soviets in line. Fortunately, GM Max Euwe was the FIDE president—he had excellent diplomatic skills. In Fischer World Champion, which I co-wrote with Euwe, he started his contribution as follows: “The battle for the world chess title has been extraordinarily enervating, but the run-up to the championship was an equally nail-biting affair.”

The run-up to the championship was an equally nail-biting affair.

—Max Euwe

Selection Of Reykjavik

After a while, just two candidate cities were left: Belgrade and Reykjavik. Fischer had a preference for the first city; he was immensely popular in the former Yugoslavia. So the Soviets could boast of their first triumph when the match was assigned to Reykjavik.

The Soviet delegation arrived in Iceland well in advance, but Fischer was nowhere to be seen. He was hiding. Around this time the whole world—not just the chess world—followed every step that Fischer made with trepidation. Could he be persuaded to travel to Reykjavik?

Finally, he boarded a plane. Two factors were presumably decisive. First of all, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had called him with an urgent request that he travel to Reykjavik as he said: “This is the worst chess player in the world calling the best player in the world.” The phone call was more proof of how important chess had become in the political world.

Another gesture may have been more important for Fischer, though. The English millionaire and chess lover Jim Slater offered to personally double the prize money to $250,000 (approx. $1.75 million adjusting for inflation). This was a decisive move. Fischer had complained that the prize money was too low. If he still refused to play, he could be considered a coward. He had to take up the fight.

Match Gets Underway

So the match was saved, but the troubles with Fischer were not over. After some complications in which Euwe played an important diplomatic role, the first game finally started on July 11. In a technical chess sense, the game was weird. On the 29th move, Fischer played an absolutely insane sacrifice that has become famous. However, he was not lost yet; his decisive mistake occurred just before the time control.

Fischer didn't show up for the second game. He had complained about the cameras in the playing hall, and he demanded that something should be done. I remember my own disappointment at the time. It seemed to be over in Reykjavik. I believe the whole chess world shared these pessimistic feelings.

However, two men came to the rescue. Kissinger made another phone call to Fischer, but more importantly, Spassky ignored the instructions of the Soviet Chess Federation that had ordered him to leave Reykjavik. Spassky's readiness to continue was brave and had consequences after the match. The Soviet authorities were not forgiving in such cases.

The third game was played in a private room—without cameras. Decades later Spassky said that he shouldn't have played the third game. Just like Fischer, he shouldn't have shown up. In that case, the psychological balance in the match would have been preserved. Theoretically, this may be a correct point of view, but it was contrary to Spassky's character to undertake such a subversive action. In any case, he played poorly in the game after Fischer had surprised him with a stunning novelty.

A painful defeat for Spassky, but he was still leading. And he could have increased his lead in the fourth game after Fischer had misplayed the early middlegame.

The narrow escape gave Fischer wings. He took the lead by winning the fifth and sixth games. Fischer had come into his stride, but Spassky's play was passive and insecure. The seventh game saw a different picture: Spassky started a wild attack in the Najdorf Sicilian. It backfired and he was happy to escape with a draw. Fischer increased his lead in the eighth game, which had a mysterious moment in the middlegame.

After a quiet draw, Fischer struck again in the high-level 10th game. He now seemed to be in complete control with a three-point lead. He may have been too self-assured at that moment. In the 11th game, Spassky came up with a new method against the Najdorf Poisoned Pawn Variation and won convincingly; Spassky's team of analysts had done an excellent job. The tension was back in the match.

After a quiet draw in the 12th game, Spassky was trailing by two points, not too alarming, considering the fact that he had so much match experience. In the 13th game, he went under, however. After a long, topsy-turvy game he made the final mistake in a drawn endgame.

Fischer had a clear edge and managed to keep it in the final phase of the match. A series of seven draws followed. The general opinion was that Spassky had recovered his form and the games were of a high level. This didn't apply to the 14th game that was marred by grave mutual mistakes. Were the players tired after the exhausting 13th game? It is difficult to answer that question. Spassky had taken a timeout after his defeat, so there were four free days. There must have been a lot of nervous tension that is not easily resolved by free days.

The next six draws are indeed quite good. An example is the tense middlegame struggle in the 19th game.

In the 21st game, Spassky needed a win to have any chance of keeping his title. He didn't get any advantage, though. He must have been disillusioned when he went under in a drawn endgame.

Fewer Mistakes

All in all, it can be concluded that Fischer won the match deservedly. He showed his ability to master many different types of positions. He was tactically alert and made only a few positional errors. In general, one can say that such a long match is won by the player who makes fewer mistakes. The match in Reykjavik was marred by bad errors. Spassky blundered in at least three games.

In comparison, in Carlsen-Nepomniachtchi, the world champion avoided any bad error, but the challenger blundered three times at the end of the match. The comparison falls short; present-day matches don't last that long. Moreover, the match in Reykjavik had extra tension because of the general interest in it and the pressure on both players to perform, especially not to lose.

The number of bad errors is not always an indication of the level of a match. Fischer and Spassky were at their best in open positions with strategic elements. They knew how to seize the initiative. Fischer had a stronger killer's instinct; this helped him to prevail.

Effect Of Championship Match

The match in Reykjavik had an enormous effect on the popularity of chess all over the world. Recently the Netflix series The Queen's Gambit aroused a similar effect on the public, but probably Fischer's achievement had an even bigger impact. I remember vividly that all chess sets were sold out after the match; everybody wanted to play. I was 20 years old at the time. If I had any doubts about becoming a chess professional, they simply faded away after the match in Reykjavik.

Chess flourished worldwide, but the breakthrough in the United States failed to materialize. Fischer had stopped playing, thus allowing the Soviets to take over again. The era of GMs Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov started and lasted until the Soviet Union fell apart.

|

GM Jan Timman was one of the world’s leading chess players from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. A candidate for the world championship several times, he lost the title match of the 1993 FIDE World Championship against Karpov. |

Previous 50th Anniversary Fischer-Spassky Content: