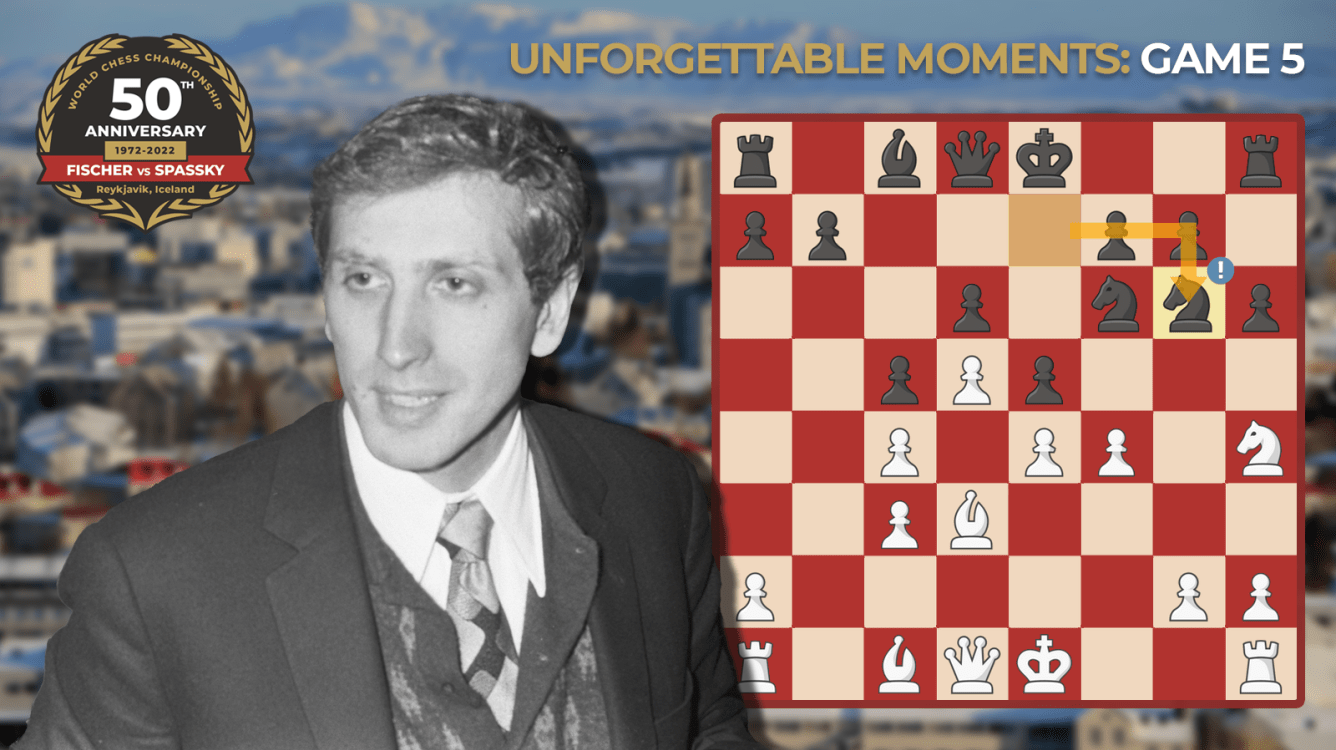

Bobby Fischer Ties Match

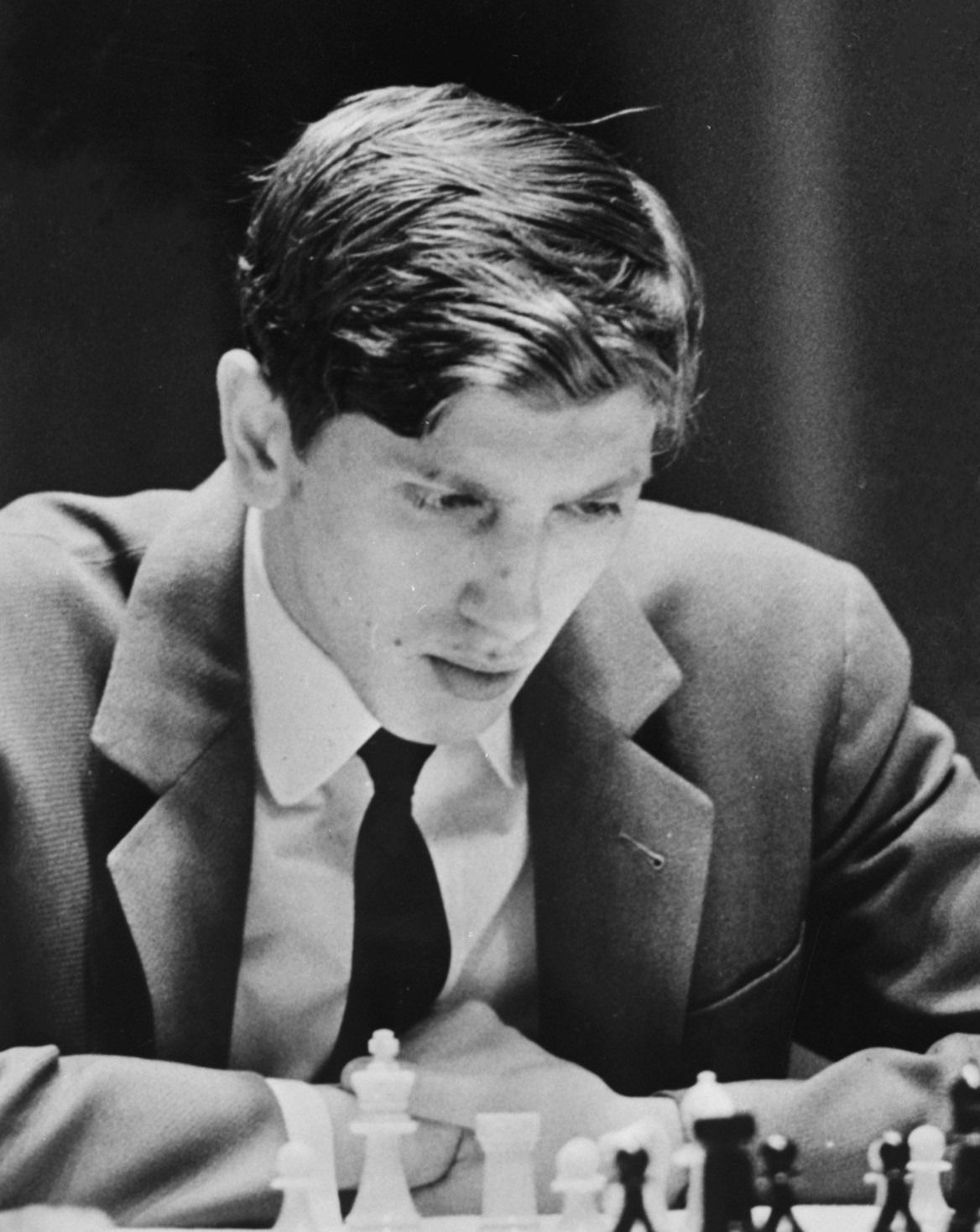

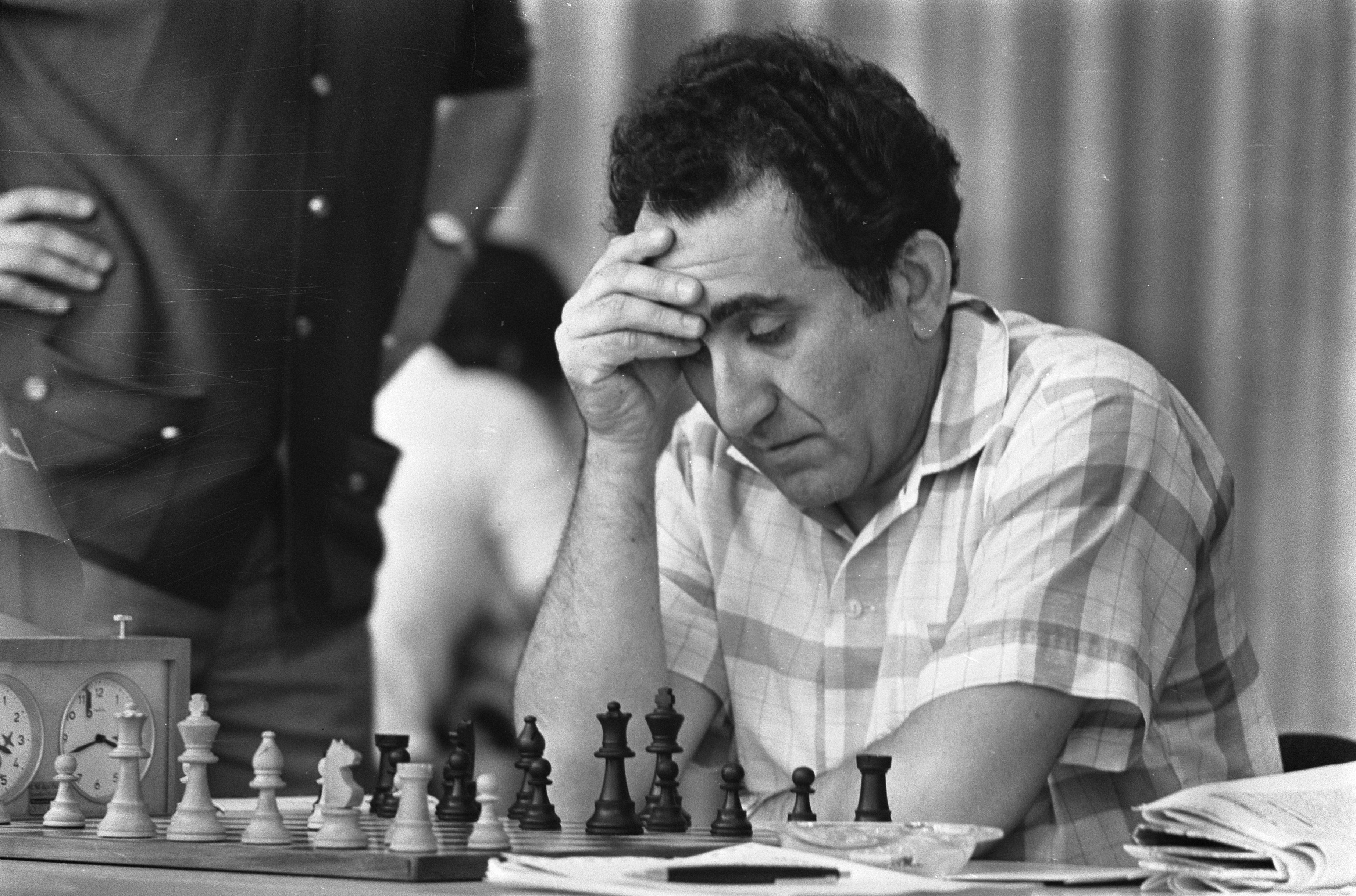

After his first-ever win against the reigning world champion, GM Boris Spassky, GM Bobby Fischer begins to face his long-held dream: Can he really win the world chess championship?

Spectators worldwide, especially in Iceland and the U.S., watch in suspense as Fischer wrestles with this question. What was it like in the "Fischer Era" of chess?

On the way to accomplishing a major goal, there are so many significant moments. Some are subtle. For Fischer, these moments were within the countless hours he spent alone at his personal chessboard, preparing for any player who dared step in his way.

They were in the hours he spent revolutionizing opening preparation by analyzing a host of openings he had never played before to such an unprecedented depth. They were in the months he locked himself in a hotel room to master rook endgames. They were in his choice to push his physical fitness to the max, combining swimming, weight-training, and racquetball to train to the degree that professional athletes do.

Then there are the big moments. The moments that are impossible to overlook. The turning point of Fischer’s defeat of the unbreakable "Iron Tigran," GM Tigran Petrosian, in their Candidates clash to seal the chance to challenge Spassky is one of those immense moments.

Game three of this match was another: Fischer’s first-ever victory against Spassky―the first crack in the wall of the dignified and seemingly unshakeable Soviet grandmaster.

These are the moments when you know you are on the precipice of achieving something greater than yourself. You can feel a vision you’ve held in your mind for so long begin to take over reality.

Entering game five, though still down a point in the match, the momentum and the quality of play were now on Fischer’s side. He stood at the front door of a dream he had carried with him since he was a child.

Fischer must have felt it. He must have begun to hear a whisper inside himself that he was really there competing for the world championship—and that it was his title to win.

The rest of the world felt it too.

On-Site In Iceland

More viewers followed the match via television than ever before―50 million viewers worldwide by the finish.

At the site of the match, Iceland―a country where unusually long winter nights lend to especially chess―the match essentially took over the island. In between match games, the local chess club, the Glaesibaer, was full of chess players and spectators playing blitz games and participating in simultaneous exhibitions. News about the match took up the front pages of local newspapers. In cafes, you could overhear customers debating Fischer’s surprising opening choice or Spassky’s critical mistake.

Initially, Icelanders didn’t take well to Fischer’s antics. Here is their rare chance to watch one of the greatest chess matches in history in the backyard of their sparsely-populated country, and the challenger is refusing to show up. Fischer’s particular and presumptuous demands did not go over well within the Nordic island’s exceptionally polite culture. But, as Fischer settled into actually playing the game he loved, he began to gain chess fans in Reykjavik.

At heart, Fischer was all chess, a game they loved too. In Profile of a Prodigy, Frank Brady describes Fischer’s reaction to agreeing to the draw in game four: "That night, Fischer dined with his friend Lina Grumette, and at one point, thinking about the game, he said almost wistfully 'Maybe I should have adjourned that game. What am I going to do with myself tomorrow?'"

Back Home In The U.S.

In the summer of 1972, Americans began to follow chess and the match like never before, kickstarting the “Fischer Era," considered to be a golden age of chess in the U.S. Chess fans of all ages would watch the games on TV, waiting for each move to be transmitted, playing through games move by move with their own boards and pieces at home, and rooting for Fischer like their lives depended on it. Regularly scheduled programs were canceled to show the match as a sports special. Games were shown live in Times Square.

In “How America Forgot About Chess,” Santiago Wills describes the urgency with which American viewers sought out the games:

WNET/Channel 13 in the New York metropolitan area was swamped with phone calls protesting the station's programming. Irate viewers repeatedly asked the television producers to drop the coverage of the Democratic National Committee meeting in Washington so that they could resume watching the play-by-play of a World Chess Championship game. In the midst of the presidential campaign that would see Nixon reelected, the American public preferred to watch the hours-long chess games between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky.

The American public preferred to watch the hours-long chess games between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky.

-Santiago Wills

Viewers were enthralled by the hours-long chess games and apprehensive about ongoings off the board: Will someone’s stopwatch be too loud? What next minor instance could prompt another boycott from Fischer?

Record numbers of chess sets were sold. Participation at tournaments reached new heights. Attendance at chess clubs surged. That year, membership at the Marshall Chess Club, one of the first chess clubs in the U.S., doubled. Fischer was a household name. In "How Bobby Fischer (Briefly) Changed America," Stephen L. Carter describes the pervasiveness of the match:

The two best players in the world were playing 24 games in Iceland, and everyone paid attention. Strangers who had never picked up a chess piece discussed the match on subway trains. Newspapers put out special editions announcing the results of the games, and vendors hawked them from the corners, shouting out the name of the winner.

The 1972 World Championship was the first time a chess match ever was televised live in real-time. In "This Time It's Personal," Mike Chase, the TV executive who brought the games to a live audience, describes the root of the idea: "No one believed chess could be a spectator sport. The way to present a match was by postgame analysis. But I realized at tournaments, that a lot of the excitement came from guessing what the next move would be. The only way to capture that excitement was to televise the games live.”

The only way to capture that excitement was to televise the games live.

-Mike Chase

In fact, trying to predict the next move became a popular pastime. The switchboards at WNET/Channel 13 would light up daily with people trying to forecast what Fischer should do next. At bars, people would bet on the next move the way they would bet on ball game plays. Shelby Lyman, the host of the live broadcast, shares his perspective in "The End of the Golden Era of Chess": "Chess is a dramatic event. You could hear the swords clang on the shields with every move. They went at each other. The average person is turned onto chess when it’s presented right. Trying to figure out the next move is a fascinating adventure—an adventure people can get into.”

Trying to figure out the next move is a fascinating adventure—an adventure people can get into.

-Shelby Lyman

Game Five

Fischer wins this game by gradually outmaneuvering Spassky and accumulating small advantages, showing a greater understanding of the essence of the position, while Spassky's moves seem rather aimless. The game opens with a Nimzo-Indian Defense, aiming to counter White's pawn center with quick development and dynamic piece play.

Position after 3...Bb4

Fischer decides to exchange his Nimzo bishop for the c3-knight, saddling Spassky with doubled c-pawns, a typical idea in this opening.

Position after 6.Bd3

With 8...e5, Fischer places all of his center pawns on the opposite color of his own bishop and blocks the e4-pawn from advancing, leaving it stuck in front of Spassky's d3-bishop.

Position after 8...e5

After Spassky plays 16.a4, Fischer spots the opportunity to give his opponent another weakness. He plays 16...a5 without hesitation. With the white a-pawn stuck on a light square, Fischer soon adds pressure to it with the simple 17...Bd7, and Spassky's queen becomes tied down to the defense of a single pawn. If the queen ever moves away and lets the pawn drop, Fischer's a-pawn would transform into a powerful protected passed pawn. Click through to see Fischer's perceptive maneuvers in action.

Position after 16.a4

Next, Fischer maneuvers to gain an advantage on the kingside, making room to improve his queen and advancing his knight to the appealing f4-square. Meanwhile, Spassky's moves seem to lack focus.

In his worse position, Spassky blunders, cutting the game short. Fischer ends up winning Spassky's weakened a-pawn. It's easy to write off a blunder as a fluke, but often it's the smaller mistakes beforehand that lead to an uncomfortable position where a player is more likely to overlook something.

David Edmonds and John Eidinow describe this monumental moment as the game finished in Bobby Fischer Goes to War:

Now the crowd erupted, breaking into a rhythmic chant: “Bobby! Bobby!" They stamped their feet and clapped their hands. In the canteen, the predominantly North European audience had a Greek moment, hurling plates and glasses into the air. With the match level at 2.5 points each, suddenly the talk was of the pressure on Spassky.

Now the crowd erupted, breaking into a rhythmic chant: 'Bobby! Bobby!'

-David Edmonds and John Eidinow

Spassky lost the third game and squandered several winning chances in the fourth, which ended in a draw, but he still had a one-point advantage and the white pieces to try to widen his margin again. His negative trend, though, continues with this game. Once again, we see an uninspired world champion during the middlegame battle, failing to create complex problems for the opponent. Fischer, meanwhile, is gaining confidence. During his entire career, he knew, like no one else, how to sense his opponent's hesitation and take advantage of it. I call the reader's attention to another brilliant idea by the challenger in the opening: on move 11, he plays a deep idea that seems to ruin his pawn structure but leads to a comfortable position for Black. This is one of Fischer's best games in the match.

In Fischer vs. Spassky: The Chess Match of the Century, GM Svetozar Gligoric shares how each player reacted to this historic game by resorting to physical fitness—with all eyes on the looming next game, now that the score was tied:

In order to celebrate victory, Fischer spent more than two hours in the hotel swimming pool the same night. Meanwhile Spassky played tennis with his helper, International Master Nei, at the court near his hotel, until dark at about 11 p.m. By then he was healthily, physically exhausted and able to forget his oversight and quickly recover for the next game.

Boris Spassky in Reykjavík, July 1972. pic.twitter.com/9dlQMKCwZ0

— Olimpiu Di Luppi (@olimpiuurcan) February 23, 2021

Game five was one of the victories that put the match on the map. GM Garry Kasparov shares its significance in My Great Predecessors IV:

At this time articles on the course of the match were published for the first time in the magazines Time and Newsweek, the latter expressing the opinion that ‘Fischer’s crushing triumph in the fifth game may signify that Spassky’s sentence has already been signed.’ And indeed, Fischer’s play became increasingly powerful with every day. Constantly changing openings, he skillfully exploited the fact that Spassky had a poor memory for variations. In matches at the highest level such play had not previously been seen: test here, dig there… Bobby was not afraid to display his curiosity.”

Do you think chess is as popular today as it was during the "Fischer Era?" Let us know in the comments below.

Stay tuned for our next article of the series, covering the incredible sixth game—unequivocally viewed as the masterpiece of the match.

Previous 50th Anniversary Fischer-Spassky Articles:

- Everything You Need To Know About Bobby Fischer

- Everything You Need To Know About Boris Spassky

- Bobby Fischer Scores 1st Win

- Bobby Fischer Forfeits Game 2

- Bobby Fischer Plays An Incredible Blunder

- 50 Years Later: Why Fischer Vs. Spassky Was The Greatest World Championship Match

- Why The Match Of The Century Almost Didn't Happen