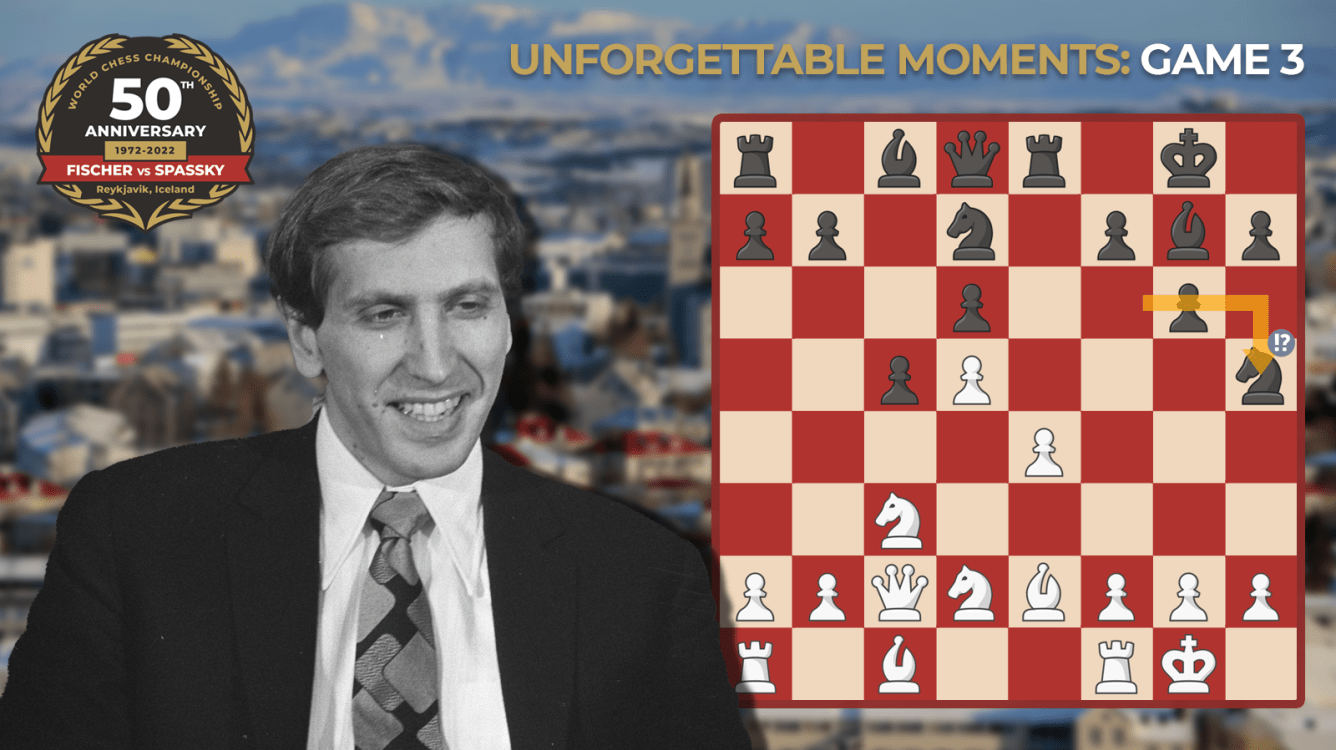

Bobby Fischer Scores 1st Win

GM Bobby Fischer shocked the world with his failure to appear for game two of the 1972 World Chess Championship. This forfeit loss put Fischer down 2-0 in the match against the reigning world champion, GM Boris Spassky.

Could Fischer make a comeback from such a deficit? Would he even return to the board to play? We take an inside look at the intriguing story from chess history that takes place off the board.

In the midst of internal and external chaos, on July 16, 1972, Fischer finds his way to the chessboard and takes his first step toward winning the match that seals his legacy as one of the greatest players ever. What was it like to defeat his chief rival for the first time?

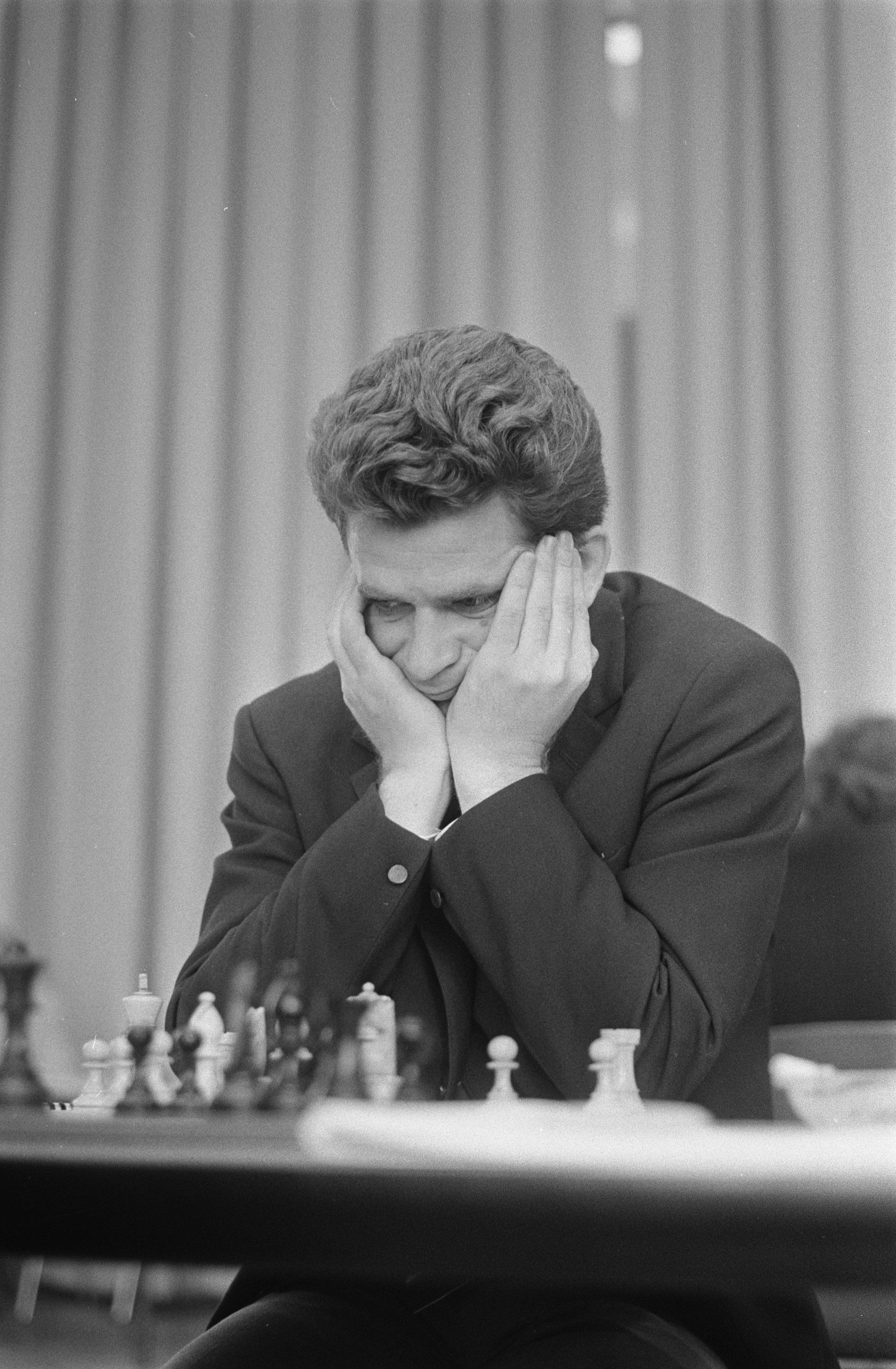

Spassky's State of Mind

Spassky arrived in Iceland with the hopes of a magnificent duel of minds on the chessboard. He was an esteemed sportsman, and he had never lost a game to Fischer. Before the match, he had three victories and remembered his most recent one at the 1970 Olympiad fondly in My Great Predecessors: Part III: “I myself don’t know how I succeeded, but before the game with Fischer I experienced that special fervor, without which high achievements are unthinkable. It is possible that Fischer himself involuntarily assisted in this: it is always pleasant for me to play against him.”

While Spassky was self-assured and collected during his first-round victory, much was taking place behind the scenes and under the surface—even before the games began. He competed infrequently. He wasn’t fully exerting himself at training sessions. And his chief trainer of many years, Igor Bondarevsky, parted from his position before the match.

During Fischer's game two forfeit, Spassky looked stressed as he waited at the empty board and withdrawn as the clocks were stopped at 6 p.m. He later shared his feelings in an interview after the match: “The only thing which was very unpleasant for me was when he refused to come on time to the match. And he didn’t come to play in the second game. I didn’t like this.”

When he didn’t come to play in the second game, I didn’t like this.

-Boris Spassky

Fischer’s antics, whether intended or not, begin to take a toll on Spassky. His deputy minister of sport, Viktor Ivonin, takes him on a long walk after the game to decompress.

Adding to the insult, Fischer immediately appeals the forfeit, meaning that Spassky's stress-inducing "free" point could be taken away after all. Rumors permeate the island of Fischer booking several flights out of Reykjavik back to the United States.

Spassky is caught in the crossfire of Fischer’s psychological battle with the organizers. He wants the match to continue and return to the game he excels at and loves. Meanwhile, Fischer’s demands grow increasingly steep and idiosyncratic. Fischer wants a chessboard with a different contrast between light and dark squares, special lighting to be flown in from Chicago, and fresh-squeezed orange juice to be brought frequently to him on stage, along with many more requests.

Spassky is pushed to counter Fischer's demands with an equally unyielding stand by Sergey Pavlov, the Soviet President of the Sports Committee. The world champion shares their tense conversation in My Great Predecessors: Part IV: “A few days before the third game I spoke for half an hour on the telephone with Pavlov, who demanded that I should declare an ultimatum, which neither Fischer, nor the organizers, nor even the FIDE President would have accepted, and the match would have been wrecked. The entire conversation consisted of an endless exchange of two phrases: ‘Boris Vasilievich, you must declare an ultimatum!’ ‘Sergey Pavlovich, I will play the match!’ After this conversation, I lay in bed for three hours, I was shaking.”

After this conversation, I lay in bed for three hours, I was shaking.

-Boris Spassky

Fischer's State of Mind

To unwind, Fischer would leave Hotel Loftleidir, located in the Oskjuhlid woodlands not far from the sea, and take long walks around the area in the middle of the night, taking in the wildlife.

During the long Icelandic summer days, the sun sets near midnight and rises just before 4 a.m. Trails weave through the Oskjuhlid hill and bunches of birch trees. Puffins fly above Faxa Bay. Minke whales emerge from the Atlantic.

The calm environment contrasts with the vast conflict taking place inside Fischer. He’s made it to the world championship. He’s closer than ever to the goal he’s strived for all his life. Yet, he’s refusing to play. He eviscerated other top grandmasters to become the challenger, yet he’s down two points to zero in this match.

Fischer has never defeated Spassky and has lost four times. The first time they met over the board, Fischer was 17 years old. It was spring in Mar del Plata, Argentina. Spassky played the King’s Gambit. Up a pawn, Fischer blundered and lost in 29 moves. It was his only loss of the 15-round tournament.

In the second loss in Santa Monica, CA in 1966, Spassky gradually ground Fischer down in a bishop vs. knight ending. Fischer finished the prestigious tournament, the Second Piatigorsky Cup, second only to Spassky. In My Great Predecessors: Part IV, GM Garry Kasparov shares his perspective on why Spassky was a challenge for Fischer: “Spassky was the most awkward opponent for Fischer. Largely because Spassky was a universal player, who subtly sensed the nuances of the struggle and all the time caught out the American by his over-straightforward desire to constantly press forward.”

Spassky was the most awkward opponent for Fischer.

-Garry Kasparov

Fischer's third loss at the 1970 Olympiad in Siegen, West Germany―the most recent one before the match―was particularly hard on him. GM Viktor Korchnoi recounts after the game: “Pale and upset, Fischer stood up from the board, after signing his capitulation. Everyone, absolutely everyone, hailed Spassky’s victory.”

Finally, there was the disaster of game one. When you've never defeated someone, they can take on an infallible quality in your imagination. The psychological duel with this unrealistic figure in your mind can become just as challenging as the battle on the board.

Fischer's Appeal

Friday, July 15, 1972, 8 a.m. local time, Fischer arrives at the hotel room of GM Lothar Schmid, the chief arbiter, to submit his official appeal of the game two forfeit—eight hours after the deadline. In Fischer vs. Spassky: The Chess Match of the Century, GM Svetozar Gligoric describes the moment: "The German grandmaster [Schmid], surprised in his room and still in his pajamas, hit the low hanging lamp with his head. Realizing that his unexpected presence was the cause, Bobby said: 'Very, very, sorry!' He was polite and extremely kind. The written protest against the forfeit was less so."

Here are a couple of highlights from Fischer's appeal:

Though from time to time I have compromised on money matters, I have never compromised on anything affecting playing conditions of the game itself, which is my art and my profession.

As you know, I have been very anxious for people in my own country, the United States, to see this event... While I wanted TV, and while it could mean a great deal of money to me personally, it is more important that the world chess championship be played under full professional conditions than that I make a personal monetary gain. The rules were designed so that the contestants could play the finest chess of which they are capable. They protect the players from interference with their concentration. My concentration has been disturbed by an evasion of these rules.

I only ask what I have always asked, that the rules providing for proper championship chess conditions be observed. Therefore I request that today’s ruling be reversed. When that happens, and when all camera equipment and supporting equipment has been removed from the hall, I will be at the chessboard. I am keen to play this match, and I hope Game Two will be scheduled for Sunday, July 16, at five in the afternoon.

I have never compromised on anything affecting playing conditions of the game itself, which is my art and my profession.

-Bobby Fischer

Where's Fischer?

Fischer's stake in the match becomes more precarious as the day of game three nears. The committee considers but ultimately rejects Fischer's appeal. In addition, the president of the International Chess Federation (FIDE), GM Max Euwe, definitively declares by telegraph that Fischer will be forfeited from the entire match if he does not show up for the third and fourth games.

Fischer is rumored to be booked on every flight departing Reykjavik, regardless of where it’s going. According to Paul Marshall, Fischer's lawyer, in Bobby Fischer Goes to War, it becomes hard to tell fact from fiction within such curious circumstances: “We kept receiving messages about Fischer being booked on various planes; a plane to New York, a plane to Greenland, every flight that went out of Reykjavik had Fischer on the flight list. And we were getting these wonderfully droll messages from an Icelander about how Fischer had booked himself on these flights and that Cramer had gone to the airport to try to dissuade him. And there were all these exciting car chases going on.”

Fischer receives a flood of communication from the U.S. asking him to stay and finish the match, including telegrams and letters from fans, a New York Times article that calls his refusal to play a tragedy, and a second call from Henry Kissinger, urging Fischer to play as his patriotic duty.

Saturday, July 15, 1972. On the day before the next game, Fischer unplugs his phone to observe his Sabbath while his team continues to fight his battle off the chessboard. Marshall reopens Fischer's appeal and argues with the committee until three in the morning. They listen but reaffirm their decision to uphold Fischer's forfeit.

Tension Beyond the Board

Sunday, July 16, 1972. Minutes before 4 a.m., the summer sun rises over Reykjavik. One of the longest days of the year begins with a question hanging over the entire city: Will the match proceed?

Two hours before the game, Fischer has a new demand: He insists that game three be played in a room behind the stage. Is this a desperate plea for compromise? Does Fischer see his chance to play the match slipping away?

Schmid calls Spassky to request the last-minute change. Without consulting his second, Spassky agrees to play in the back ping-pong room of the venue, Laugardalsholl Arena. What would Fischer have done if Spassky had said no?

Minutes before the start time, over a thousand spectators gather in the main hall to watch the game on closed-circuit televisions. A car waits for Fischer. All the lights on the roads from Hotel Loftleidir to the playing venue are set to green.

Spassky arrives first, wearing a gray suit and scarlet tie. He walks with his usual stately yet approachable demeanor through the entrance. As he gets settled in the makeshift playing room, he tests out Fischer's chair. This unusual moment is captured by Frank Brady in Profile of a Prodigy: “Spassky appeared on time; at first sat in Fischer’s chair, and, perhaps unaware that he was on camera, smiled and swiveled around several times as a child might do. Then he moved to his own chair, and waited.”

Spassky... smiled and swiveled around several times as a child might do.

-Frank Brady

Fischer arrives at Laugardalsholl. As he exits the car, he is immediately surrounded by crowds of spectators and photographers. He moves erratically through the chaos to the glass front doors.

In the ping-pong room, Fischer sits down across from Spassky in his custom-leather swivel chair. Instead of focusing on the Staunton-style pieces, poised for a duel of minds, on the wooden board before him, Fischer notices a camera. It's a single closed-circuit television camera, wrapped in blankets, installed to show the game to the rest of the world: to the audience in the original playing hall, to the commentators analyzing on demonstration boards, and to the journalists in the press room.

Fischer's cordiality at the board disappears. He reacts fervently, as described by David Edmonds and John Eidinow in Bobby Fischer Goes to War:

Fischer roared at Schmid: 'No cameras!' He prowled the room, turning switches on and off. Schmid protested that Spassky was being disturbed. Fischer yelled back at him to shut up.

Fischer roared at Schmid: 'No cameras!'

-Edmonds and Eidinow

White-faced, Spassky stood. Lothar Schmid recollects, "When Bobby started to fight again, Boris became upset and he said, 'If you do not stop the quarreling, I will go back to the playing hall and demand to play there.'" With the challenger turning the World Chess Championship into a verbal brawl, Schmid, panic-stricken, pleaded with the champion to continue the game. "Boris, you promised." He turned to Fischer. "Bobby, please be kind."

Schmid remembers: "I felt there was only one chance to get them together. They were two grown-up boys, and I was the older one. I took them both and pressed them by the shoulders down into their chairs. Boris made the first move, and I started the clock."

After hesitating a few minutes, Fischer makes his first move. Though it's silent in the tiny playing room, the audience is applauding in the main hall. The Match of the Century will be played after all. Kasparov later remarked: “The match really began from the third game.”

The match really began from the third game.

-Garry Kasparov

Game Three

Spassky opens with 1.d4, and Fischer responds by playing the Benoni (3...c5), a dynamic and risky choice.

Position after 3...c5

As the players develop their pieces and near the middlegame, Fischer plays the surprising 11...Nh5!?. This is the single most memorable move of the match for me. Fischer moves his knight to the edge of the board, willingly offering Spassky the opportunity to wreck his kingside pawn structure by capturing the wayward knight with his bishop.

Position after 11...Nh5!?

Why did Fischer play such a move? He chooses the chance to activate his pieces and create counterplay over limiting attachment to dogma and the fear of long-term weaknesses. In addition, the groundbreaking idea was more likely to catch Spassky off-guard than the main lines.

Spassky accepts Fischer's offer, exchanging his bishop for the knight and breaking apart Fischer's kingside pawn chain. Fischer uses his newfound space to mobilize his queen and knight, soon creating attacking threats.

Position after 15...Ng4

To parry the threats, Spassky has to trade knights with 16. Nxg4, allowing Fischer to reconnect his pawn chain. From there, Fischer steadily improves his pieces, maintains his bishop pair, and gains a protected passed pawn. As each move progresses, his pieces become more focused than Spassky's. Click through to see Fischer's improvements in action.

Position after 20.Rael

Once Fischer has improved his pieces to the max, he breaks through and wins Spassky's e4-pawn.

Position after 31.R3e2

With the opposite-color bishops, Spassky retains drawing chances in the endgame, so Fischer focuses his energy on attacking the king. He meticulously weaves his queen and bishop into Spassky's position to win another pawn, leaving him with two connected passers on the queenside.

Spassky later recounts this game as the turning point of the match: “I saved Fischer, by playing the third game. In this game I essentially signed my capitulation of the entire match.”

This is Fischer's first-ever win against Spassky. Brady captures this monumental moment in Fischer's life: “By the time he reached the backstage exit, he could no longer resist a smile for the well-wishes waiting there. It was undoubtedly one of the happiest moments of his life.”

It was undoubtedly one of the happiest moments of his life.

-Frank Brady

This is Fischer's first win against Spassky, not just in the match but in his career. This game is a turning point—Spassky begins to crumble after this defeat, making unusual mistakes for such a high-class player. Over the years, I've read a lot of comments that Fischer just crushed Spassky in the match, but this seems to be misguided by the final result and exaggerated feelings cultivated by the passage of time. At that moment, when starting the third game, with a 2-0 score in the match and a historical score of 4-0 against Fischer (not counting the fateful second game of the match, naturally), it would be natural to anticipate a victory for the Soviet chess player.

Looking back at this game, I see how small details change the course of history. Fischer tries a bold move on the Benoni Defense, a risky decision. The opening is a success for White—if Spassky had made the right choice on move 15, he would have a clear advantage and would probably have won the game. But starting with this move, it looks like the Spassky we know just disappeared.

From here, the match focuses far more on the chess element than drama off the board.

Do you think Spassky should have taken a stand against playing in the ping-pong room? Would Fischer have played if he had? Let us know in the comments below.

Previous 50th Anniversary Fischer-Spassky Articles:

- Bobby Fischer Forfeits Game 2

- Bobby Fischer Plays An Incredible Blunder

- 50 Years Later: Why Fischer Vs. Spassky Was The Greatest World Championship Match

- Why The Match Of The Century Almost Didn't Happen